Davos 2026: A Spirit of Dialogue in a Contested World

OHK was on the ground in Davos, tracking how cooperation, growth, people, innovation, and sustainability are being reframed under pressure.

Power in a Small Place: During the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2026, Davos, a small Alpine town temporarily becomes a global decision space, hosting debates on cooperation, growth, innovation, people, and planetary limits. The physical scale of Davos offers a reminder that the world’s most consequential conversations often unfold within very constrained environments.

Davos Is Not a City. It Is a Condition—Davos is not a city in the conventional sense. It is a village that temporarily carries the weight of the world. For most of the year, it is defined by stillness, winter light, and routine. In January, it becomes something else entirely: a compressed global arena where governments, corporations, investors, activists, and institutions converge to shape—or at least narrate—the future. In 2026, that contrast felt sharper than ever. The mountains stood immaculate and indifferent, while below them temporary structures of power appeared almost overnight. Streets were rerouted. Storefronts transformed into embassies of influence. Conversations unfolded at speed, under pressure, and often behind glass. OHK was present not just to participate in the spectacle, but also to observe its mechanics—how space, narrative, and power interact when the world gathers in one small place.

Reading Time: 20 min.

All photos are copyrighted and may not be used, reproduced, or distributed without prior written permission.

Summary: Davos 2026 unfolded against a backdrop of permanent constraint rather than temporary disruption. Framed by the theme “A Spirit of Dialogue,” the forum revealed a global system no longer seeking to restore consensus, but learning how to operate within fragmentation. Cooperation was treated as negotiated and selective rather than assumed; growth as conditional and resilience-driven rather than expansive; innovation as inseparable from governance and legitimacy; investment in people as economic infrastructure critical to stability; and sustainability as a field of unavoidable trade-offs rather than ambition statements. Across themes, the dominant insight was realism: trust is uneven, resources are constrained, and systems must function despite misalignment. Davos 2026 did not point toward a unified future, but toward the practical challenge of managing interdependence in a contested world.

A Spirit of Dialogue, Under Pressure: Observations from Across Davos 2026

Davos always looks calm from a distance: blue skies, snow-bright mountains, a village scale that feels almost too small for global ambition. But the atmosphere in 2026 was not defined by calm — it was defined by compression. Compression of time, access, messaging, and attention.

The official umbrella theme — “A Spirit of Dialogue” — was not merely decorative language. It was a response to something tangible: a world where shared assumptions are fraying, and where the ability to even speak in a common vocabulary is becoming harder. Dialogue, in Davos 2026, was treated as a tool of survival for systems under stress — not a soft ideal.

1) Cooperation in a Contested World: What Davos 2026 Actually Showed

A Commons Under Pressure: Kulturplatz Davos was conceived as a shared civic space—open, non-branded, and deliberately inclusive, positioned to soften the edges of power surrounding the Forum. In Davos 2026, its openness did not fragment dialogue, but quietly exposed how conditional cooperation has become. Designed to invite convergence, the space instead revealed how global actors now meet: nearby, attentive, but rarely aligned—reflecting the gap between the ideal of dialogue and its current practice.

The Davos 2026 conversation on cooperation was shaped by fragmentation—not only between states, but between narratives. The same word (security, resilience, stability, sovereignty, fairness) often meant different things depending on the speaker and the room. What stood out most was how cooperation has shifted from being an assumed default to being a negotiated achievement. The architecture of Davos makes this visible: national houses, branded pavilions, invitation-only dialogues—all signalling that “global conversation” is now conducted through tighter channels and sharper positioning. This is where Davos becomes instructive: it reveals that cooperation, rather than operating as a baseline condition, now emerges only under specific conditions—shaped by risk, leverage, and selectively shared trust.

One of the most consistently explored questions at Davos 2026 was how cooperation can function in a world defined by contestation rather than consensus. This question surfaced repeatedly across the official World Economic Forum programme, including plenary discussions, Open Forum sessions, and high-level panels framed around Global Risks, Resilience, Peace and Security, and Geopolitics in a Fragmenting World. Across these sessions, cooperation was rarely discussed as a stable or assumed condition. Instead, it was framed as something fragile, situational, and increasingly difficult to sustain across divergent political and economic systems. Speakers frequently returned to the idea that the international environment has shifted from one of alignment to one of negotiation — not just between countries, but between interpretations of shared concepts.

Terms such as security, resilience, sovereignty, and fairness appeared repeatedly in public discussions, yet their meanings varied sharply depending on whether they were used in the context of energy, trade, technology, or social stability.

When Dialogue Meets the Frontline: Outside the Ukrainian House in Davos, the language of cooperation intersects directly with geopolitical reality. In Davos 2026, “contestation” was no longer abstract: security, sovereignty, and survival shaped conversations as much as growth or innovation. This image captures the limits of dialogue — and its necessity — reminding participants that global cooperation is now negotiated in the shadow of real conflicts, not above them.

This lack of shared definition was especially evident in sessions addressing supply chains and economic security. In discussions grouped under the Global Risks framing, cooperation was often described as desirable but constrained by national imperatives. Rather than calls for broad multilateral solutions, the dominant tone was pragmatic and selective: cooperate where interests overlap, manage competition elsewhere, and accept fragmentation as a structural condition rather than a temporary disruption. The same dynamic emerged in sessions focused on peace and security. While dialogue remained the stated objective, it was clear that trust is no longer evenly distributed. Cooperation was discussed less in terms of shared values and more in terms of risk mitigation — avoiding escalation, preventing systemic shocks, and maintaining minimum levels of coordination in critical areas such as energy markets, financial stability, and emerging technologies.

This shift was reinforced not only by what was said, but by how Davos itself was organised. Much of the most substantive dialogue took place in national houses, institutional pavilions, and controlled formats rather than open multilateral settings. The physical layout of the forum mirrored the geopolitical reality under discussion: dialogue still exists, but it is increasingly segmented, curated, and conditional. Taken together, the sessions and settings at Davos 2026 revealed a recalibration of expectations. Cooperation is no longer framed as a global default or a shared horizon. It is treated as a negotiated outcome — one that must function in environments where trust is partial, interests diverge, and alignment cannot be assumed. In this sense, Davos did not offer a solution to global fragmentation. It offered something more candid: a recognition that cooperation itself must now be redesigned for a contested world.

2) How Can We Unlock New Sources of Growth: What Davos 2026 Revealed

Unlocking new sources of growth. The GCC arrives at Davos this year not louder than last— just more deliberate: At Davos this year, the GCC narrative feels noticeably recalibrated. Qatar and Saudi Arabia remain highly visible, but the tone has shifted from last year’s headline-driven storytelling toward a more deliberate emphasis on capital discipline, partnerships, and delivery. The confidence is still there—it’s just expressed differently. Notably, NEOM, once the undeniable centerpiece of Saudi Arabia’s Davos presence, is no longer front and center in the way it was before. Instead of anchoring the narrative around a single megaproject, Saudi messaging this year points to sequencing, reprioritization, and a broader portfolio of growth engines—from industry and logistics to technology and private-sector participation. The ambition remains, but it is being paced. Qatar, meanwhile, continues to project stability, institutional readiness, and long-term capital alignment, reinforcing its role as a steady and credible partner rather than a loud disruptor. Together, this reflects a maturing GCC posture at the World Economic Forum: fewer grand symbols, more operational signals.

Growth in Davos 2026 was not discussed as a single global story. It was discussed as a competition among models: energy-led growth, tech-led growth, investment-led growth, productivity-led growth—each carrying its own assumptions about society and governance. A key shift was the emphasis on growth under constraint: constrained by geopolitics, supply chain risk, demographic transition, and the cost of capital. Growth was repeatedly framed as something that must be resilient, not just fast—and that resilience has a price. You could see this in how countries and institutions presented themselves: not just “we are open for business,” but “we are stable, investable, bankable, strategically positioned.” Across sessions framed around Economic Growth, Trade and Investment, Energy and Materials, and The Global Economy, growth emerged as a contested and differentiated concept — shaped as much by political constraints as by economic ambition.

Rather than restating a fragmented growth narrative, discussions focused on how these competing models are being operationalised in practice. Energy-led growth was discussed in the context of security and transition; technology-led growth in terms of productivity and control; investment-led growth through capital availability and risk perception; and productivity-led growth through workforce transformation and automation. Each model carried implicit assumptions about governance, state capacity, and social tolerance for disruption. What was notable was that few speakers framed growth as purely market-driven. Instead, growth was increasingly discussed as something that must be actively structured, enabled, and protected. These constraints became visible in how governments and institutions positioned themselves toward investors and partners. Geopolitics, supply chain fragility, demographic change, fiscal pressure, and the rising cost of capital were not treated as external shocks, but as permanent conditions. In sessions addressing the global economy and trade, growth was repeatedly linked to resilience — the ability to withstand disruption rather than simply maximise output. This reframing marked a departure from earlier Davos conversations, where speed and scale dominated. In 2026, resilience was acknowledged as a prerequisite, even when it implied slower or more selective expansion.

This shift was visible not only in discussions, but in how countries and institutions positioned themselves throughout Davos. National houses and investment pavilions moved beyond generic “open for business” messaging. Instead, they emphasised stability, regulatory predictability, institutional credibility, and long-term bankability. Growth narratives were tightly coupled with signals of governance strength and strategic positioning. The implicit message to investors was clear: in a volatile world, growth flows toward environments that reduce uncertainty, not just promise returns. What Davos 2026 ultimately revealed is that growth is no longer framed as a global public good that will naturally diffuse. It is increasingly viewed as a scarce outcome — competed for, conditioned by trust, and shaped by political and institutional capacity. Unlocking new sources of growth, in this context, is less about discovering new sectors and more about designing systems capable of sustaining confidence under constraint.

3) How Can We Better Invest in People: What Davos 2026 Made Clear

eKhaya: Investment Begins with Belonging: Inside South Africa’s Davos space, the concept of eKhaya— meaning “home”— framed investment in people in explicitly social terms. Rather than leading with technology, productivity metrics, or automation, the space foregrounded belonging, dignity, and social cohesion as preconditions for economic participation. This was not presented as sentiment, but as strategy: an acknowledgment that workforce development, skills, and growth cannot be separated from trust, inclusion, and shared identity. The choice stood in deliberate contrast to much of the surrounding Davos landscape, where AI, automation, and frontier technologies dominated both visual presence and narrative. While those showcases focused on accelerating productivity and scaling innovation, eKhaya quietly made a different argument—that technological progress, however advanced, rests on social foundations that cannot be automated. South Africa’s framing suggested that in societies marked by inequality and historical exclusion, investing in people begins not with tools, but with restoring a sense of place and participation. In Davos 2026, this position underscored a broader reality: without belonging and legitimacy, even the most sophisticated growth strategies risk becoming economically and politically fragile.

This theme surfaced repeatedly in a more practical way than many expect. “Investing in people” was framed as a core economic strategy — because every other ambition (innovation, productivity, sustainability) collapses without skills, trust, and social cohesion. In Davos 2026, investing in people meant: (i) workforce transformation (skills, re-skilling, mobility), (ii) inclusion as economic necessity (not charity), (iii) and the political consequences of inequality. The sharp insight is that human investment is now treated as a stability policy. The global economy can survive slower growth; it cannot survive prolonged legitimacy crises. In that sense, education, capability, and inclusion were discussed as foundational conditions for economic stability and system performance.

At Davos 2026, investing in people was no longer framed as a secondary social objective or a long-term aspiration. Across sessions addressing Jobs and Skills, The Future of Work, Economic Inclusion, and Social Cohesion, human investment was treated as a core economic strategy — one that underpins every other ambition discussed at the forum. This year marked a shift toward practicality. Rather than abstract commitments to education or inclusion, discussions focused on implementation pressures: how quickly workforces must adapt, how unevenly skills are distributed, and how limited institutional capacity has become in many contexts. Workforce transformation emerged as an urgent challenge, driven simultaneously by automation, demographic change, and shifting labor mobility. Participants across sectors acknowledged that productivity gains from technology will not translate into stability unless skills development keeps pace — and that re-skilling at scale remains institutionally difficult.

Inclusion was discussed not as a moral imperative, but as an economic necessity. Across sessions on growth and competitiveness, inequality surfaced repeatedly as a destabilising force — eroding trust, constraining demand, and amplifying political risk. The emphasis was less on redistribution and more on participation: access to education, formal employment pathways, and mobility across sectors and regions. In this framing, inclusion became a precondition for economic function rather than a corrective measure applied after growth occurs. A notable shift in Davos 2026 was the explicit acknowledgment of the political consequences of underinvesting in people. Discussions on social cohesion and governance linked inequality directly to declining institutional legitimacy, policy resistance, and reform fatigue. Several sessions highlighted how skills gaps and exclusion can harden into long-term structural divides, making future transitions — whether digital, energy-related, or fiscal — increasingly difficult to implement.

The underlying insight that emerged across these conversations was stark. The global economy can absorb slower growth, higher costs, or technological disruption. What it cannot absorb indefinitely is a breakdown in legitimacy. In that sense, education, skills development, and inclusive access were treated as non-negotiable requirements for economic and political stability— as essential to stability as transport networks or energy systems. Investing in people, at Davos 2026, was framed not as social policy, but as a form of economic risk management.

4) How Can We Deploy Innovation at Scale and Responsibly: What Davos 2026 Made Explicit

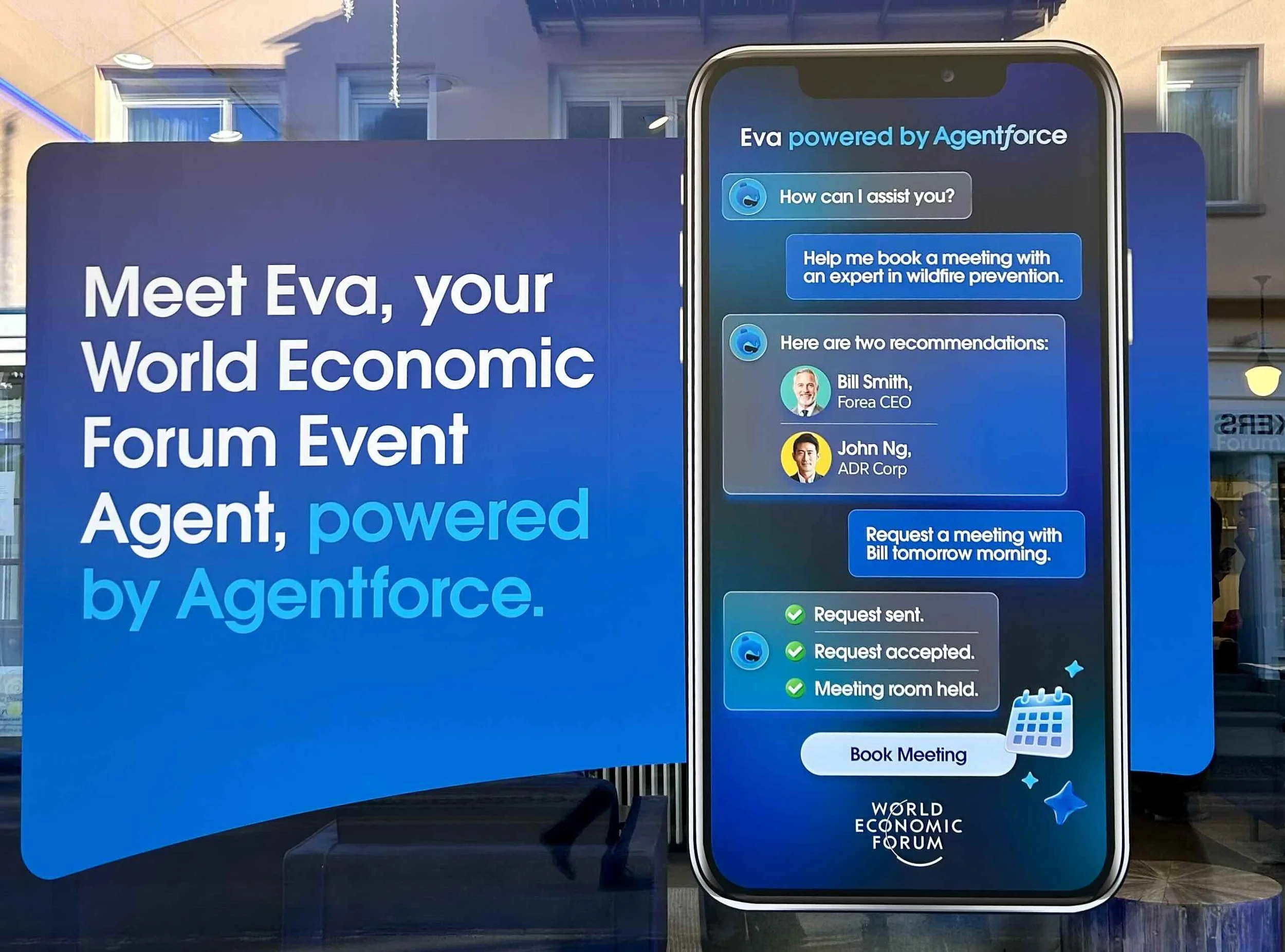

Innovation at scale doesn’t always look revolutionary: Eva, the World Economic Forum’s AI-powered event agent, is the product of a collaboration with Salesforce, built to demonstrate how AI can move from concept to operational infrastructure. Rather than showcasing a bold technological moonshot, Eva reflects a quieter shift: intelligence embedded directly into real workflows—scheduling meetings, matching expertise, coordinating logistics—seamlessly and at scale. This year’s Davos emphasis is less about what AI could do and more about what it is already doing when deployed responsibly within trusted institutions like the World Economic Forum. The focus is efficiency, usability, and delivery, signaling a broader transition from visionary narratives to applied systems that simply work. Eva is a reminder that today’s innovation agenda is increasingly about integration rather than disruption—technology designed to disappear into the background. The question it leaves us with is whether this quiet effectiveness represents progress itself, or merely a more sophisticated way of managing transformation at scale.

Innovation in Davos 2026 came with a double demand: scale and responsibility. The world wants frontier tech — especially AI — but no longer accepts “move fast” as a governing philosophy. The real tension is not whether innovation will spread, but who gets to set the terms: (i) Who defines responsible deployment, (ii) Who audits systems, (iii) Who bears harm when systems fail, and (iv) Who benefits first. Davos conversations treated governance as part of innovation itself—not a brake on progress, but a requirement for legitimacy. The presence of technology platforms in high-visibility spaces underscored a reality: innovation has become inseparable from influence, and influence now operates through infrastructure, ecosystems, and access.

At Davos 2026, innovation was no longer discussed primarily as a question of possibility. Its inevitability was assumed. The central question, repeated across sessions on Artificial Intelligence, Digital Transformation, Innovation Governance, and The Future of Industry, was how innovation can be deployed at scale without undermining trust, stability, or institutional legitimacy. What distinguished this year’s conversation was the clear rejection of “move fast and fix later” as a governing philosophy. While frontier technologies — particularly AI — were widely framed as essential to productivity, competitiveness, and growth, there was equal emphasis on the risks of uncontrolled deployment. Innovation was presented not as neutral progress, but as a force that actively reshapes power, labor, and information systems.

Across discussions, the tension was not about whether innovation will spread, but about who sets the terms of its spread. Responsibility was repeatedly linked to governance capacity: who defines acceptable use, who audits systems at scale, who absorbs social or economic harm when systems fail, and who captures value in the early stages of adoption. These questions were not framed as ethical side debates; they were treated as core determinants of political and market legitimacy. A notable shift in Davos 2026 was the way governance itself was reframed. Rather than being positioned as a constraint on innovation, governance was discussed as a prerequisite for scale. Without shared rules, accountability mechanisms, and public confidence, participants acknowledged that even the most powerful technologies risk backlash, fragmentation, or regulatory overcorrection. Responsible innovation, in this context, was presented as a strategy for sustaining momentum rather than slowing it.

The physical presence of technology platforms across Davos reinforced this dynamic. Innovation was not confined to panels or demonstrations; it was embedded in the infrastructure of the forum itself. High-visibility pavilions, branded lodges, and curated spaces positioned technology firms not merely as solution providers, but as conveners and system architects. This underscored a broader reality: innovation at scale now operates through ecosystems and access, not standalone products. Taken together, Davos 2026 revealed a recalibration in how innovation is understood. Scale remains the ambition, but legitimacy has become the condition. The future is not defined by who innovates fastest, but by who can align technological capability with governance, accountability, and trust — at speed and at scale.

5) How Can We Build Prosperity within Planetary Boundaries: What Davos 2026 Confronted

Where Climate Talk Hit the Ground: The Climate Hub at Davos 2026 marked a clear break from previous years. For the first time, sustainability was given a dedicated physical presence at the Forum, moving the conversation out of closed rooms and into the everyday environment of Davos itself. In earlier editions—including 2025—climate discussions centered on ambition, targets, and long-term pathways, with little attempt to translate planetary limits into lived systems. In 2026, the Climate Hub reframed climate action as an operational challenge. The introduction of visible, on-site interventions around the Hub, including small electric mobility solutions, was not meant as a showcase of technological breakthroughs, but as a demonstration of constraint—how climate considerations begin to shape infrastructure, movement, and behavior when ambition encounters geography, cost, and feasibility.

This theme carried a more mature tone in 2026—less about aspiration, more about implementation trade-offs. “Planetary boundaries” was not treated as an abstract moral framing, but as a practical constraint shaping investment decisions, industrial policy, and competitiveness. The central tension running through discussions was: how do you decarbonize without destabilizing? And behind it: how do you transition fairly across countries with unequal resources and unequal exposure? This theme linked directly back to growth, people, and cooperation — because sustainability is now the arena where all contradictions surface at once: equity vs urgency, national interest vs global commons, and innovation vs governance.

By 2026, the conversation around sustainability at Davos had noticeably matured. Across sessions addressing Climate and Nature, Energy Systems, Sustainable Industry, and The Future of Infrastructure, the focus had shifted away from long-term aspiration toward immediate implementation trade-offs. “Planetary boundaries” were no longer framed primarily as a moral imperative; they were treated as an operational constraint shaping economic strategy, investment decisions, and competitiveness. The defining question was no longer whether decarbonisation should occur, but how it can be achieved without destabilising economies, societies, or political systems. Discussions consistently returned to the tension between speed and stability. Participants acknowledged that rapid transitions carry real distributional impacts — on jobs, energy prices, fiscal space, and social cohesion — and that these impacts vary dramatically across countries with unequal resources, capacities, and exposure to risk.

Fairness emerged as a central, unresolved issue. Across sustainability-focused discussions, there was an implicit recognition that global climate targets cannot be pursued through uniform expectations. Emerging and developing economies emphasised the constraints they face: limited access to capital, higher vulnerability to shocks, and the need to balance climate action with development imperatives. At the same time, advanced economies wrestled with domestic political resistance to transition costs. The result was a sustainability conversation grounded less in consensus and more in negotiation. What made this theme especially consequential in Davos 2026 was how directly it linked back to the forum’s other core questions. Growth strategies were increasingly evaluated through their environmental feasibility. Investment in people was framed as essential for managing transition impacts and maintaining legitimacy. Innovation was discussed as both an enabler of decarbonization and a source of new governance challenges. Cooperation surfaced as indispensable, yet increasingly selective—shaped by uneven costs, asymmetric benefits, and divergent national constraints.

In this sense, sustainability functioned as the arena where all contradictions surfaced at once: urgency versus equity, national interest versus global commons, and technological capability versus institutional readiness. Davos 2026 did not resolve these tensions. It made clear, however, that prosperity within planetary boundaries will depend less on ambition statements and more on the capacity to manage trade-offs transparently, fairly, and at scale. Davos 2026 did not offer clarity — it offered realism. And realism, in a contested world, may be the most valuable starting point available.

Cross-Cutting Focus Areas That Defined the Mood

When Data Became the Backbone of Sustainability: This image captures a defining undercurrent of Davos 2026: the quiet elevation of computational capacity as a prerequisite for both climate action and economic competitiveness. The visible presence of data and AI infrastructure firms—including Snowflake—signaled that sustainable growth is no longer debated only in terms of policy ambition or technological promise, but in terms of analytical capability, governance capacity, and control over the systems that measure, model, and optimize the economy. Across discussions on climate strategy, energy systems, and sustainable industry, decarbonization was framed as a data-intensive challenge. Energy grids, supply chains, industrial processes, and reporting regimes increasingly depend on advanced modeling, real-time analytics, and AI-enabled optimization. This reframing exposed a growing fault line: countries and institutions with access to robust computational infrastructure are better positioned to manage transition costs, attract capital, and comply with evolving standards, while others risk exclusion or penalization. AI, in this context, was no longer treated as a discrete innovation sector. Its physical and symbolic prominence at Davos reflected its role as economic infrastructure — shaping productivity, labor markets, and state capacity. The central question was no longer whether transformation will occur, but who has the systems, skills, and institutions to manage it — and who does not.

1) Sustainable Growth, Climate Strategy, and Computational Capacity

Sustainability discussions at Davos 2026 revealed how closely climate action is now intertwined with technological and analytical capacity. Decarbonization pathways were increasingly framed in terms of data, modelling, and optimization — from energy systems and grids to industrial processes and supply chains. At the same time, concerns surfaced around unequal access to these capabilities. Countries with advanced technological and analytical infrastructure are better positioned to manage transition costs, attract capital, and meet reporting requirements, while others risk being excluded or penalized. As a result, climate alignment was discussed not only as an environmental challenge, but as a technological and institutional one. The underlying implication was clear: the ability to operate within planetary boundaries is increasingly mediated by access to AI-enabled systems and governance capacity.

2) Technology Transformation and AI as a Systemic Force

AI at Davos 2026 was not presented as a discrete sector or innovation theme. It functioned as a structural force shaping labor markets, productivity, governance capacity, and competitive advantage. The tone was notably pragmatic. The question was no longer whether AI would be adopted, but how institutions would cope with its speed and scale. Labor displacement was discussed as an imminent challenge rather than a hypothetical one, with repeated acknowledgement that workforce adaptation will lag technological capability. Governments signalled growing urgency around standard-setting and oversight, not to slow innovation, but to avoid dependency on external systems they do not control. The physical prominence of AI firms across Davos reinforced this reality: AI is no longer a product — it is infrastructure, and whoever governs infrastructure shapes the rules of the economy.

3) Investing in People, Inclusion, and the AI Transition

Across discussions on inclusion, skills, and social cohesion, AI emerged as both a driver of opportunity and a source of risk. Workforce transformation was framed explicitly in relation to automation, algorithmic decision-making, and shifting skill requirements. The concern was not simply job displacement, but the speed at which labor markets and education systems can respond. Several discussions acknowledged that societies unable to manage this transition risk deepening inequality, political backlash, and erosion of trust. Inclusion, in this context, was no longer framed as social policy, but as a stabilising response to technological disruption. The implicit message was that AI-driven growth without parallel investment in people is not only unjust, but economically and politically unstable.

How This Felt Different from 2025—and from Five Years Earlier

A Forum Under Visible Pressure: Demonstrations have long accompanied Davos, but in 2026 they felt different in character and meaning. Rather than isolated or single-issue protests positioned at the margins, the marches visible this year were broader, more heterogeneous, and more proximate to the daily movement of the Forum. Groups carrying national flags and geopolitical symbols moved through central areas of the town, intersecting directly with the rhythms of Davos rather than remaining a parallel spectacle. What distinguished 2026 was not the existence of protest, but its alignment with the tone inside the Forum. Five years earlier, demonstrations stood in contrast to a Davos narrative built around consensus, global cooperation, and shared direction. Even in 2025, protest felt episodic, reflecting crisis-related frustration rather than structural division. In 2026, the marches echoed the same realities discussed in plenary sessions: fragmentation, contested legitimacy, and limits to collective action. The proximity of people marching underscored a shift in atmosphere. Davos no longer felt insulated from geopolitical tension or public grievance. Instead, it operated within it. This mirrored a broader change in leadership rhetoric, where cooperation was no longer assumed to be expandable, stability was negotiated, and alignment was partial rather than universal. The image reflects a forum adjusting to persistent contestation — not as disruption, but as a permanent condition.

Compared with OHK’s attendance in 2025, and even more so when set against Davos five years earlier in 2020, the shift in 2026 was less about form and more about emphasis. In 2020, Davos still carried a strong sense of consensus-building optimism — growth, globalization, and technology were discussed as broadly shared opportunities, with governance framed as something that would eventually catch up. By 2025, that optimism had already narrowed, replaced by caution and risk awareness. In 2026, however, the tone hardened further: systems were no longer discussed as aspirational, but as constrained; technology was no longer framed primarily as possibility, but as power; and cooperation was no longer assumed to be expandable, but something to be preserved selectively. What changed most noticeably was the absence of language about “getting back on track.” Davos 2026 felt less like a forum trying to restore a previous order, and more like one adjusting to a permanent condition of fragmentation, constraint, and negotiated stability.

A clear illustration of this change came from the public special addresses and plenary sessions by political leaders at Davos 2026, particularly those focused on geopolitics, security, and economic stability. Unlike earlier years, these speeches did not frame global cooperation as a return to shared rules or a rebuilding of a unified order. Instead, they consistently acknowledged fragmentation as a given condition. What stood out was not confrontation, but restraint. Leaders spoke carefully about alignment, resilience, and strategic autonomy, often avoiding universal language in favour of conditional commitments. Cooperation was framed as something to be maintained where possible — in trade, climate coordination, financial stability, or technology standards — rather than expanded wholesale. The tone was pragmatic, cautious, and openly shaped by geopolitical limits.

This was markedly different from Davos 2020, where public speeches still emphasized restoring trust in globalization, and from 2025, where the focus was on managing crisis fallout. In 2026, leaders spoke as if the system had already changed—and that their task was to operate within it, not fix it. Davos 2026 marked a further shift. The tone suggested that the objective is no longer to rebuild a unified system, but to prevent instability within a permanently contested one.

At OHK, our presence at Davos is not symbolic. We attend because Davos remains one of the few places where global systems—economic, political, technological, and environmental—can be observed interacting in real time. For us, it is not a forum for slogans, but a field site for understanding how power, constraint, and decision-making are evolving under pressure. As a hybrid consulting firm combining management consulting, economic planning, and international development, we operate at the intersection of policy ambition and implementation reality. Attending Davos allows us to test assumptions, listen closely to how leaders frame risk and trade-offs, and understand where global consensus is fraying—and where it is being rebuilt selectively. This perspective directly informs how we advise governments, development institutions, and private-sector leaders working in ethically complex and politically constrained environments. What Davos 2026 reinforced is that strategy today cannot be separated from governance capacity, technological infrastructure, or social legitimacy. Our role as consultants is to translate these global shifts into grounded, actionable strategies embedding accountability, transparency, and long-term public value into every recommendation. We attend Davos not to predict the future, but to better equip our partners to navigate it responsibly. Contact OHK if you would like support in preparing for Davos or engaging in the Forum with clear strategy, evidence, and purpose.