Designing the Future from Scratch:

Global Pathways to Greenfield Development

From frontier homesteads to futuristic free zones, land policy is destiny: How nations transform untouched land into engines of growth—and who gets to build the future.

Land is more than just territory—it is power, potential, and a silent architect of the future. The way nations distribute and govern land has long determined not only where cities rise and people settle, but also who builds wealth, who controls growth, and who is left behind. From ancient empires to modern states, land policy has shaped the course of development. In the modern era, it remains the single most decisive factor in how populations expand, economies flourish, and urban landscapes evolve—especially when starting from scratch on undeveloped land. This article begins with a contrast between two familiar models: the United States, where decentralized land ownership and frontier homesteading allowed millions to claim and develop land freely, and Egypt, where a highly centralized system has kept most land under government control, limiting organic growth and concentrating 100+ million people on just 4% of the country’s territory.

But these two countries tell only part of the story. Across the world, other models have emerged. Dubai offers a top-down, vision-led approach where the state retains ownership but leverages strategic zoning, private investment, and bold branding to build cities out of sand. China, with its state-owned land system, has pioneered special economic zones where market forces and infrastructure work in sync. Rwanda emphasizes inclusivity and sustainability, guiding development through long-term planning and community engagement. India uses land pooling and infrastructure-first strategies to balance rural rights with urban growth. And Ethiopia channels greenfield planning into employment-focused industrial parks supported by donor investment. Each of these models offers a different answer to the same question: What happens when a country faces a blank slate of land—and the opportunity to shape what comes next? This article explores those answers. It compares how different nations develop untouched land into productive, populated, and often iconic new regions. It examines the political philosophies behind each model, the trade-offs they entail, and what lessons they offer for countries seeking to grow not only fast—but fairly.

Because ultimately, how a country governs its land determines who gets to shape its future.

Reading Time: 40 min.

How America Claimed the Land and Built a Nation Through Decentralized Ownership, Settler Incentives, and Private Urban Expansion

When the United States was still a fledgling nation, one of its most transformative policy decisions came not in foreign affairs, industry, or banking—but in land allocation. Beginning in the 18th century and accelerating through the 19th, the U.S. federal government adopted a model of land grants, private ownership, and open settlement that directly catalyzed one of the fastest and widest population spreads in modern history. At the core of this model was the belief that land should be accessible to individuals—that settlers, farmers, and entrepreneurs, not just aristocrats or governments, should be able to claim land, improve it, and profit from it.

The Homestead Act: Legalizing the American Dream—Perhaps the most symbolic example was the Homestead Act of 1862. Signed by President Abraham Lincoln, this law granted 160 acres of public land to anyone willing to settle it, build a dwelling, and farm it for at least five years. Millions took advantage of this law—European immigrants, freed slaves, and poor Americans among them. The result was the rapid development of the American Midwest, Great Plains, and Western territories. The message was clear: land equals opportunity. And when you empower people with land, you don’t just give them shelter—you give them a stake in the future. How U.S. Cities Grew from Land Claims? Let’s look at how this played out in practice, with examples of U.S. cities that rose because of private land ownership and decentralized development.

As we delve into three examples of U.S. cities, our team did a fun exercise to look at Egypt—where one of our offices is located and where we've done a lot of master planning—to get a sense of the numbers and ask: what would it look like if Egypt had followed the same land-led models that built major U.S. cities like Portland, Denver, and Chicago? By projecting American-style land allocation, migration incentives, and infrastructure-led speculation onto Egypt’s geography—from Marsa Matruh to South Sinai to the Upper Egypt rail corridor—we explored how these policies might have shaped population distribution, economic activity, and long-term urban form in underutilized parts of the country. To generate these comparative metrics, we used a scenario-based modeling approach that adapts key parameters from historical U.S. land development programs—such as the Homestead Act and the Donation Land Claim Act—to Egypt’s geography and demographics. We assumed similar land grant sizes (typically 160–640 acres per family), adjusted for Egypt’s total arable and desert land, and factored in population density, migration trends, and infrastructure accessibility. We then projected settlement patterns, population absorption, and GDP contributions using U.S. benchmarks for urban growth rates, land productivity, and employment generation. Our model also integrated Egypt-specific constraints—such as water availability and economic activity clusters—to ground the estimates in realistic conditions. The goal was not to replicate outcomes but to test what Egypt's spatial and economic landscape might look like if it had deployed a land-led development strategy akin to that of 19th-century America, with an emphasis on distributed land rights, citizen-led expansion, and infrastructure-backed settlement.

The Economic Titan Among Land-Claim Cities—Chicago stands out as the most economically powerful city among the U.S. land-claim cities discussed. From its strategic location at the intersection of rail and waterways, Chicago’s explosive growth was fueled by land speculation, infrastructure investments, and private development. Today, the Chicago metropolitan area is home to approximately 9.5 million people and generates an estimated $900 billion in GDP, making it the third-largest economy in the United States after New York and Los Angeles. To put Chicago’s economic scale into context, GDP per capita offers a useful comparison with other cities discussed in this article. Chicago, with an estimated GDP of around $900 billion and a metro population of about 9.5 million, yields a per capita GDP of approximately $94,700. Shenzhen, one of China’s most successful Special Economic Zones, has a GDP of roughly $500 billion with a population close to 17 million, resulting in a per capita GDP of about $29,400. Dubai’s economy stands at around $120 billion with a population of 3.7 million, translating to approximately $32,400 per capita. Meanwhile, Greater Cairo, with a population of roughly 22 million and an estimated GDP of $200 billion, has a per capita GDP of just around $9,100. This stark contrast highlights how Chicago—built on land-led development, industrial clustering, and private capital formation—delivers far greater individual economic productivity. Even with fewer people than Shenzhen or Cairo, it generates significantly more economic output per person. These figures provide important scale as we later examine the land and growth models of Dubai, Shenzhen, and Cairo, and reflect how early choices around land, infrastructure, and institutional capacity can shape long-term prosperity.

Portland, Oregon: A City Shaped by Federal Land Policy—Portland's emergence was catalyzed by the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850, which granted up to 640 acres per married couple in the Oregon Territory. Over 7,000 land claims were filed between 1850 and 1855, covering approximately 2.5 million acres in Oregon. Portland itself originated from overlapping claims by early settlers such as Asa Lovejoy and Francis Pettygrove. Its riverside geography was secondary to the enabling legal framework that turned vacant land into capital. Today, the Portland metro area spans over 6,684 km², houses a population of approximately 2.5 million, and contributes over $200 billion annually to regional GDP. Its current land value and zoning patterns still reflect the gridded parceling system established under early land claim policies. If Egypt had done something similar in the Western Delta fringe or Marsa Matruh in the 1980s—allocating 2.5 million acres (roughly 10,000 km²) to 7,000–10,000 families and securing their rights through clear land titling—today that area could host 2.5 million residents and generate over $20 billion in annual GDP. Currently, these regions remain underdeveloped and thinly populated, illustrating what could have been with the right enabling legal and economic frameworks.

Denver, Colorado: The Self-Initiated Urban Economy—Denver was founded in 1858 during the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, with no formal federal planning—just a convergence of private claims, resource extraction, and speculative layout. Early settlers filed under preemption laws and the Homestead Act of 1862, claiming 160-acre parcels individually. By 1870, more than 10,000 claims had been filed in Colorado Territory. The Denver-Aurora metro now covers over 21,000 km², with a population exceeding 3 million. Its regional GDP surpasses $250 billion, powered by finance, tech, energy, and aerospace. Land rights were converted into tradable assets, setting the basis for a real estate-driven economy decades before formal statehood. If Egypt had followed a similar homesteading model in South Sinai or the Eastern Desert, granting land in 0.65 km² parcels to 10,000 Egyptians over 6,500 km² of desert could have been populated and monetized. This could have seeded a population of 3 million and an economy rivaling the size of Egypt’s entire Red Sea and South Sinai GDP combined—at more than $60 billion. The missed opportunity lies in the absence of legal homesteading frameworks and incentives to permanently settle these zones.

Chicago, Illinois: Infrastructure and Legal Certainty Drive Scale—Chicago’s rise was underpinned by the Public Land Survey System (PLSS) and government auctions post-1830, when Illinois land was formally surveyed and sold. Vast tracts were purchased via General Land Office sales, with over 4 million acres sold in Illinois by 1850. Chicago’s location at the junction of Lake Michigan and emerging railroad corridors turned it into the Midwest’s commercial gateway. Today, the Chicago metropolitan area spans over 28,000 km², with a population of ~9.5 million and an annual GDP exceeding $770 billion. The city's explosive 19th-century growth was rooted in well-defined property rights, legal title security, and speculation mechanisms that tied land to logistics and financial capital. If Egypt had enabled a similar model along the Upper Egypt rail corridor—between Beni Suef and Sohag—by putting 28,000 km² of land into private hands and letting capital flows and population movements shape cities, it could have generated a new urban zone for 9 million people and produced over $150–200 billion in GDP. Today, these governorates remain low-density, and land remains overwhelmingly under public control with limited secondary markets, stunting their full urban and economic potential.

Why the U.S. Model Worked—and Still Works? The success of the U.S. in transforming vast tracts of empty land into thriving cities and productive regions lies in its early and decisive commitment to decentralized, private land ownership. Unlike systems where land remained under tight state control, the United States empowered individuals to claim, develop, and own land directly. This policy didn’t just reflect a political ideology of individualism; it created real, durable economic incentives. Settlers were able to build homes, start farms, and establish businesses on land they legally owned, fostering a deep sense of investment and long-term stewardship. This ownership, in turn, enabled people to build equity through property, using it as collateral or as a means to pass wealth across generations. Because the system allowed markets to determine land use, cities and towns emerged where they made the most sense—near rivers, railroads, ports, or trade routes—not where a central planner thought they should be. Urban areas developed organically around opportunity, infrastructure, and mobility. Land became an engine of growth in itself: it could be bought, sold, leased, mortgaged, and improved, unlocking a dynamic real estate and finance sector.

This flexibility allowed the country to expand rapidly, distributing population and opportunity across the continent. Even today, the legacy of this model persists. Cities like Austin, Phoenix, and Charlotte continue to experience rapid population growth and economic diversification, largely due to flexible land use policies, responsive planning, and secure ownership laws. Individuals and businesses can acquire land quickly, develop it with limited interference, and respond rapidly to market demand—often outpacing state initiatives. This environment fosters innovation, supports a robust middle class, and anchors a culture of local agency and responsibility. While not without its flaws—especially concerning environmental impact and displacement of Native American populations—the U.S. model has demonstrated extraordinary capacity to convert greenfield territory into livable, investable, and evolving human settlements. It shows that when people are given clear rights to land and the freedom to act on those rights, cities and economies don’t need to be built by decree—they build themselves. Though the U.S. homestead model is centuries old, its age doesn’t make it irrelevant—because the core challenge it addressed—how to transform uninhabited land into inclusive, productive territory—remains central to modern greenfield development.

Shirley Plantation, Virginia—America’s oldest family-owned business, continuously operated since 1638. As one of the earliest land grants in colonial America, Shirley represents nearly four centuries of unbroken land tenure, economic adaptation, and intergenerational value creation. While the socio-political context is vastly different, the enduring lesson is clear: clear land rights and enforceable claims lay the foundation for investment, continuity, and long-term development. In a world of rapidly launched greenfield cities, the U.S. experience reminds us that the age of a claim does not determine its relevance—its clarity does.

Empowering Individuals at Scale: A Radical Experiment That Worked—What made the American land model so radical in global terms was not just its scope—but its faith in ordinary individuals. Unlike hierarchical or bureaucratic models of development, the U.S. land strategy assumed that common people, if granted secure rights and minimal conditions, could not only survive but thrive on unclaimed territory. This wasn’t merely about farming—it was a bet on self-governance, infrastructure, and even democracy taking root from the ground up. Over 270 million acres, or roughly 10% of the U.S. landmass, moved from federal to private hands through homesteading programs—reshaping the physical and political geography of the nation. This decentralization enabled cities and entire regions to emerge organically—not as the outcome of top-down planning, but of dispersed risk-taking and individual ambition. Markets formed naturally around access points—rivers, railways, and mineral seams—rather than around administrative capitals. Property ownership meant more than shelter; it became a foundation for civic identity, economic mobility, and intergenerational wealth. While the model had deep imperfections, especially in its displacement of Native communities and the inequalities it sometimes entrenched, it remains one of the clearest demonstrations in history of how land rights—widely distributed—can accelerate both settlement and national cohesion.

Egypt’s Constrained Geography and Control—Trapped on 4%: How Egypt’s State Land Control Stifles Growth, Limits Opportunity, and Constrains Urban Expansion

Now, contrast this with Egypt—a country of over 100 million people, where more than 95% of the population lives on just 4% of the land. Most of Egypt is desert, but not uninhabitable. The challenge isn’t geography alone—it’s governance. In Egypt, the state owns the vast majority of the land. Individuals and developers must navigate complex bureaucracies to acquire or lease land. Even large-scale projects often face years of delay due to red tape, unclear regulations, or overlapping jurisdiction among government bodies. The result? Urban sprawl on the fringes of Cairo, a lack of organic city development across the country, and an overwhelming pressure on the Nile Valley and Delta regions. Without secure, tradable land rights, ordinary Egyptians lack the incentive or ability to build, invest, or move beyond traditional urban cores.

Why Egypt’s Model Limits Growth? Egypt’s land governance model, rooted in centralized state control, has long hindered the country’s ability to expand equitably or strategically into its vast uninhabited territories. While Egypt possesses more than one million square kilometers of land, over 100 million Egyptians are squeezed onto just 4% of it—mostly along the Nile Valley and Delta. This isn’t due to geography alone; it’s the product of how land is controlled, accessed, and regulated. In Egypt, the government retains ownership over the vast majority of land and manages it through a fragmented bureaucratic structure involving multiple ministries and agencies. As a result, acquiring land for housing, farming, or enterprise is often slow, opaque, and fraught with legal ambiguity. This centralized control stifles innovation: cities do not emerge simply because the state announces them. They thrive when people are free to settle, build, and trade. Instead of allowing this organic growth, Egypt frequently launches top-down “new city” projects far from population centers, only to find them underutilized or unaffordable for the average citizen.

Compounding the problem is the fact that land is not liquid in Egypt. Many Egyptians cannot use land as collateral to obtain financing or investment due to unclear or insecure tenure arrangements, limiting both entrepreneurship and household mobility. Without widespread access to formal land markets, millions turn to informal development—constructing homes on unregistered plots, often without utilities or legal protection. Informal settlements now house a significant share of the urban population, straining infrastructure and governance. Meanwhile, high population density in already-inhabited areas pushes land prices upward, deepening social inequality and making it difficult for families or small businesses to relocate or expand. Even where greenfield development is technically possible—in desert areas beyond Cairo or in the Sinai—barriers to ownership, investment, and services deter movement. Egypt’s growth potential is thus constrained not by lack of land, but by policies that prevent people from accessing, owning, and developing it. Until a serious land governance reform agenda is undertaken—focused on decentralization, tenure security, and market transparency—Egypt’s massive spatial imbalance will persist, and its new urban ambitions will remain disconnected from the real needs and capabilities of its people.

President Gamal Abdel Nasser distributes land titles to Egyptian farmers under the landmark 1952 Agrarian Reform Law. The program redistributed over 1.5 million feddans (≈630,000 hectares) to approximately 350,000 families, capping ownership at 200 feddans and reshaping Egypt’s rural economy. While initially agricultural, much of this land now lies within or adjacent to expanding urban peripheries. By some estimates, more than 40% of the redistributed plots—especially near Greater Cairo, the Delta, and Upper Egypt towns—have since been urbanized or lost to informal settlement expansion, often without formal zoning or infrastructure. This moment, once a symbol of agrarian justice, is now a starting point for understanding how land clarity, urban encroachment, and long-term planning intersect—and how past reforms, if not supported by modern land governance, risk fragmentation and underutilization.

Beyond Decrees: Why Top-Down Cities Struggle? Egypt’s reliance on large-scale, state-led urban developments—such as New Cairo, 6th of October City, and the New Administrative Capital—highlights the limits of a model that lacks pathways for ordinary citizens to directly acquire and develop land. These projects are often launched far from existing population centers and allocated to major state-connected developers through opaque processes. Without inclusive mechanisms like homesteading, land pooling, or secure small-scale ownership, many of these new cities remain sparsely populated or function as elite enclaves. Meanwhile, the informal sector fills the vacuum left by formal inaccessibility, offering millions shelter but little legal protection. In addition, there is structural rigidity over flexibility. Another core obstacle is Egypt’s fragmented and overlapping land governance. With multiple agencies managing land access and unclear titling even in formal developments, individuals and businesses face constant risk of legal disputes. Land, unlike in more market-based systems, is rarely treated as a liquid asset—it cannot easily be bought, sold, or mortgaged, further deterring investment. Infrastructure in many new developments often arrives after the fact, rather than serving as a tool to draw in settlers. Until land becomes both accessible and tradable for the broader population, Egypt’s ambitions to build outward will continue to face structural resistance rooted not in geography—but in governance.

From Concentrated Estates to Fragmented Plots—To fully understand Egypt’s current land challenges, we must recognize that the country once tried to replicate the American model of land-based empowerment. In the 1950s and 60s, President Gamal Abdel Nasser launched one of the most ambitious land reform efforts in the developing world—breaking up large aristocratic estates and redistributing agricultural land to millions of small farmers. Much of Egypt’s arable land was controlled by a small elite. After the 1952 revolution, Nasser introduced agrarian reforms to dismantle feudal land ownership. The state capped landholdings (first at 200 feddans, then less), seized large estates, and redistributed them to smallholder farmers. Like the U.S. Homestead Act, the goal was to create a nation of landowners, reduce inequality, and build a more equitable rural economy. But while the American model focused on opening up new, unsettled lands to individual ownership and development, Nasser’s reform targeted Egypt’s most productive farmland—already tightly bound by geography and limited in supply. The result was a fragmented agricultural landscape, where smallholders often lacked the resources, capital, or scale to modernize. Meanwhile, Egypt’s vast deserts—its true frontier lands—remained firmly under state control, undeveloped and inaccessible to ordinary citizens. Instead of encouraging greenfield settlement or entrepreneurial expansion into new territories, the state kept a tight grip on land allocation, pushing top-down schemes that rarely aligned with real market demand or community needs. What began as an effort to democratize land ended up limiting mobility and locking millions into narrow strips of cultivable land along the Nile. In contrast to the American trajectory of outward settlement and dynamic city formation, Egypt’s land strategy remained bound by control, caution, and bureaucratic rigidity—undermining the very goals the reform initially set out to achieve.

So rather than unleashing private development or allowing people to settle new towns, the state became the gatekeeper of expansion, choosing when and how new areas could be developed. This approach lacked flexibility, local initiative, and market responsiveness. If Egypt had paired land reform with a policy to open up barren land for public settlement and ownership, it might have replicated aspects of the U.S. Homestead model. Instead, it preserved state ownership of uninhabited areas while fragmenting valuable cultivated zones—undermining both agricultural modernization and greenfield urban expansion. Unlike in the U.S., where land ownership became a path to wealth, collateral, and expansion, Egypt’s reforms created small, often non-viable landholdings without connecting them to broader opportunities in housing, finance, or urbanization. Instead of decentralizing settlement, the reform entrenched dependence on the narrow Nile corridor—reinforcing Egypt’s spatial imbalance for generations to come.

Yet despite these systemic constraints, Egypt offers a rare but important counterexample—one where localized authority has been empowered with real mandate and impact. The Tourism Development Authority (TDA), where OHK has been directly involved, stands out as a quasi-local entity with a national mandate, operating with far more independence and agility than typical government bodies. It has overseen the development of Egypt’s most successful large-scale, master-planned tourism zones—from Gouna and Makadi to Port Ghalib and Nabq. These areas are not just functional—they are globally competitive tourism destinations, built on clear planning frameworks, streamlined land release processes, and infrastructure-first thinking. Crucially, the TDA model shows that when a sectoral agency is granted land authority, planning coherence, and implementation tools, Egypt can deliver orderly, market-ready development. This stands in stark contrast to the chaotic, ad hoc urban sprawl seen in tourism towns like Hurghada, where weak governance has led to disorganized growth, infrastructure gaps, and long-term environmental stress. This experience is not just an outlier—it’s a critical proof of concept. As the following China section will show, development accelerates when land governance is coupled with empowered, motivated institutions that are allowed to act like developers, not just regulators. Egypt’s tourism zones offer a glimpse of what’s possible when that principle is applied—even within a highly centralized system.

Dubai’s Bold Blueprint: How Vision, Capital, and Control Built a Desert Metropolis

Dubai’s model for greenfield development represents a striking contrast to both grassroots settlement and over-centralized stagnation. It is a state-led, vision-driven experiment that has turned arid desert into a global commercial hub. In this model, the state doesn’t just regulate or facilitate—it acts as the architect, master planner, and strategic developer. The ruling families and government entities retain ownership of most land but release it to private developers through long-term leases, selected freehold areas, and highly defined regulatory frameworks. These frameworks offer investors both security and clarity, key ingredients that distinguish Dubai from countries burdened by legal ambiguity or bureaucratic paralysis. Beginning in the early 2000s, Dubai opened specific zones where foreign nationals could purchase real estate, a game-changing move that catalyzed a construction boom and transformed the city’s skyline. Projects like Dubai Marina, Business Bay, and the Palm Jumeirah weren’t accidental; they were deliberately planned, strategically located, and marketed as icons of luxury, innovation, and ambition.

Dubai’s rapid ascent from barren coastline to a global urban icon exemplifies the power of state-led, investment-driven greenfield development. In just over two decades, the city expanded its urban footprint by over 500 square kilometers, driven by aggressive land reclamation, infrastructure sequencing, and centralized planning. Visible here is the Burj Al Arab, a symbol of Dubai’s high-brand real estate strategy, located on an artificial island—a hallmark of its speculative yet controlled urban expansion. In the background, the Burj Khalifa pierces the skyline at 828 meters, anchoring the Downtown district developed by Emaar, a state-linked entity. Between 2000 and 2020, Dubai's population grew from 862,000 to over 3.3 million, with land prices in strategic zones increasing by more than 800%. Dubai’s model hinges on aligning zoning, infrastructure, and capital in a tightly governed ecosystem, where over 85% of the land is state-owned but leased or sold under conditional frameworks that ensure alignment with macroeconomic and branding goals.

The government’s role was not to micromanage but to set clear incentives, provide infrastructure up front, and move fast—creating an enabling environment rather than a restrictive one. The city’s branding became as valuable as the land itself: it was sold as a gateway, a lifestyle, a statement of global relevance. Dubai also built ahead of demand, investing early in transport, water, electricity, and connectivity. This infrastructure-first approach added value to land even before the first tower rose. While this model has proven successful in building global visibility and attracting billions in real estate capital, it comes with caveats. It is inherently top-down and elite-driven, relying on a centralized vision to dictate what gets built and by whom. Local participation is limited, and the city’s affordability and social inclusivity remain under scrutiny. The government decides the rules, selects the players, and sets the pace. That makes it efficient—but not necessarily democratic or equitable. Moreover, the model depends on a government that can act like a fast-moving developer, not a slow bureaucracy—a condition not replicable everywhere. Yet, despite these trade-offs, Dubai offers a powerful case of how control, vision, and private capital can rapidly transform uninhabitable land into a functioning, globally recognized city—if the governance environment is right.

But the success of the Dubai model hinges on far more than just real estate liberalization or land sales. Several interlocking ingredients have made this transformation possible—without which the entire model would likely have failed or stagnated. First, Tight Urban Control and Centralized Decision-Making—Dubai’s development authority—the Dubai Municipality, alongside powerful arms like Nakheel, Emaar, and the Roads and Transport Authority—exercises comprehensive oversight over zoning, building regulations, design guidelines, and infrastructure sequencing. Nothing is left to piecemeal or ad hoc development. Every major project, district, or sector unfolds within a broader, master-planned urban vision that is continuously refined. This high degree of urban control ensures design coherence, infrastructure coordination, and efficient land use—a far cry from informal sprawl or unregulated expansion. Second, Rigid Oversight over Building Codes and Architectural Standards—Building in Dubai means conforming to strict codes that cover not just safety and environmental performance, but also aesthetics and urban form. Developers must submit to rigorous design approvals, traffic impact studies, sustainability certifications, and compliance checks—creating a level of discipline that prevents haphazard development and maintains the city’s curated appearance. This architecture of oversight supports the city’s brand as modern, luxurious, and globally competitive.

Third, Open Policy Toward Foreign Residents and Investors—A cornerstone of Dubai’s model is its proactive openness to expatriates—not only to work, but also to live and invest. Foreigners can acquire property in designated freehold zones, open businesses under favorable conditions, and even obtain long-term residency through golden visa schemes tied to investment thresholds. This legal openness created a powerful global draw: people from over 200 nationalities now live and invest in Dubai, bringing with them capital, expertise, and demand. Fourth, Use of International Planning and Design Expertise—Dubai deliberately turned outward for knowledge and aesthetics. It hired world-renowned architects, urban designers, engineers, and consultants from Europe, the U.S., Japan, and beyond to help shape its built environment. From signature towers designed by starchitects to master plans influenced by global best practices, the city has been shaped not only by local vision but by imported expertise. This global input helped Dubai bypass trial-and-error phases that slower-growing cities must often endure.

And very importantly—contrast this to Egypt—Dubai follows a model of “Infrastructure First, Development Second.” Where Egypt often announces new cities without laying the foundational infrastructure needed to make them livable or investable, Dubai does the opposite. Highways, metro systems, desalination plants, power grids, ports, and airports are built before the first tower rises. This anticipatory approach transforms empty desert into viable economic zones, turning land from barren plots into investable, functional territory. In Dubai, the value of land is not inherited from proximity to legacy urban centers—it is created by infrastructure itself. Connectivity comes first, allowing population and investment to follow. Unlike Egypt’s repeated struggles with ghost cities—where housing is built without transportation, utilities, or services—Dubai’s strategy ensures that even peripheral areas become economically relevant from day one. It is not a model of waiting for demand to justify infrastructure, but one of using infrastructure to generate demand.

In addition, Branding as an Economic Development Tool—Dubai’s land is not just sold—it’s marketed as part of a larger lifestyle proposition. The city invests in branding itself as a global hub of luxury, safety, innovation, and opportunity. Tourism, business, and real estate are tightly interlinked through messaging, events (like Expo 2020), and high-profile developments. Every district is a brand: Downtown Dubai, Dubai Marina, Jumeirah Lakes Towers. This has created a halo effect that boosts land values and investor confidence. This approach has distinguished Dubai from its regional peers. Many Gulf and Middle Eastern cities have tried to replicate Dubai’s architectural ambition or branding, but few have matched its sequencing of infrastructure and development. And that success is made possible by another essential ingredient: administrative agility and political will. Dubai’s leadership—particularly under the Maktoum family—operates more like a unified corporate board than a fragmented government bureaucracy. This structure enables tight coordination across planning authorities, infrastructure agencies, and developers. Permits are issued quickly, approvals are streamlined, and regulatory enforcement is both consistent and strategic. Unlike Egypt, where overlapping ministries, unclear jurisdiction, and bureaucratic delays can stall projects for years, Dubai offers an environment of regulatory clarity and execution speed.

A frequently cited pillar of Dubai’s development model is its low-cost, flexible labor market, powered primarily by migrant workers from South Asia. Construction wages in Dubai can range between $200 to $400 per month, with limited labor protections, no right to unionize, and sponsorship systems that tie workers to their employers. This has enabled rapid construction of megaprojects—towers, highways, ports—at relatively low cost and high speed. Critics rightly point out the ethical and human rights concerns surrounding this model, but from a purely economic standpoint, it delivers fast, affordable urban growth. However, this should not be seen as a structural advantage that Egypt lacks. In fact, construction wages in Egypt are even lower, often ranging between $100 to $200 per month, with a vast pool of underemployed or informally employed labor. Egypt’s challenge isn’t the cost of labor—it’s the cost of bureaucracy, uncertainty, and delays. Even with cheap labor, development is stifled when land tenure is unclear, permitting is slow, and infrastructure arrives years after the first residents. Dubai’s model is not universally replicable—but it’s not impossible either. What makes Dubai unique isn’t just the cost of labor, but the alignment of land policy, infrastructure investment, regulatory clarity, and administrative speed. Most cities in the region, including Cairo, have similarly affordable labor forces—but without institutional agility, strategic sequencing, and investor confidence, the cost advantage is wasted. Labor is only one input in a much larger system. Egypt’s failure to convert its own low-cost labor into fast, scalable development reflects policy gaps—not structural barriers.

Dubai doesn’t treat land development as a standalone activity—it is deeply embedded within a broader economic strategy that integrates real estate with targeted sectors such as finance, logistics, tourism, education, and technology. Purpose-built zones like DIFC (Dubai International Financial Centre), D3 (Dubai Design District), and Dubai Internet City are more than just clusters of buildings—they are spatial ecosystems backed by customized regulatory frameworks, streamlined licensing, and international-grade infrastructure. These zones offer tax incentives, legal autonomy, and investor protections that attract multinationals, startups, and capital simultaneously. Real estate becomes not just a destination, but a platform for broader economic transformation.

But what truly sets Dubai apart—yet is often underappreciated—is its institutional machinery, particularly its legal and judicial system. Despite being staffed significantly by Egyptian-trained legal professionals, Dubai’s court and legal systems function with far greater speed, predictability, and investor alignment. Specialized courts, like those within DIFC, follow international common law principles, operate in English, and are known for swift resolution of disputes. This system dramatically reduces uncertainty for developers, investors, and tenants—helping projects move forward faster, with less friction. By contrast, Egypt’s legal system, though rich in expertise, remains slow, heavily bureaucratic, and often unclear in its handling of land disputes, zoning issues, or development rights. Cases can drag on for years, and overlapping jurisdiction among courts, ministries, and local authorities further delays outcomes. This undermines investor confidence and forces developers into risk-averse, defensive postures. Land becomes a liability rather than a launchpad. Dubai’s experience shows that strategic sectoral integration cannot succeed without regulatory clarity and legal enforcement mechanisms that match its ambition. It is not merely the availability of land or capital that transforms a city—it is the ecosystem of enforceability, incentives, and sectoral alignment that turns physical space into economic opportunity. Egypt, with its legal talent and vast pool of underutilized land, could replicate this model in part—but only if it fundamentally retools its legal framework to support integrated, accountable, and investor-ready development.

China’s Engineered Cities: Special Zones as the Blueprint for Scalable Urban Expansion

China’s approach to greenfield development is defined by a paradox: total land ownership by the state, paired with an aggressive embrace of market logic within designated zones. This hybrid model has produced one of the most dramatic urban transformations in human history, beginning with the establishment of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) like Shenzhen in the 1980s. At that time, Shenzhen was a quiet fishing village near Hong Kong. Within decades, it became a sprawling high-tech city of over 17 million people, fueled by a combination of favorable tax policies, foreign investment, and extensive infrastructure development—all built on land that remained under government control. In this system, the government doesn’t sell land but grants long-term leases (often 40–70 years) for residential, industrial, or commercial use. The land-use rights become tradable commodities, enabling developers and businesses to act with confidence even in the absence of full ownership. What makes the model powerful is the local government’s incentive to drive growth: municipalities generate revenue by leasing land and reinvesting proceeds into infrastructure and urban services. This has turned cities into active engines of growth, each competing to attract investment, talent, and industries.

Shenzhen, China: The World’s Most Successful Special Economic Zone—Once a fishing village with fewer than 30,000 residents in 1980, Shenzhen has transformed into a global innovation and manufacturing hub with over 17 million people today. Designated as China’s first Special Economic Zone, it attracted massive foreign direct investment through land leasing reforms, export-oriented industrial policies, and integrated infrastructure planning. Shenzhen now contributes over $475 billion to China’s GDP and hosts headquarters of global tech giants like Huawei and Tencent. This image, taken from Lianhua Mountain Park, captures the city’s dense skyline and planned urban core—an enduring symbol of how strategic land use and governance can drive exponential growth.

The model also ensures coordination between physical planning and policy—tax incentives, power plants, highways, and business licensing are developed simultaneously, allowing new zones to become operational in record time. This synergy has produced not only Shenzhen but also Pudong in Shanghai, Binhai in Tianjin, and the ambitious Xiong’an New Area, all developed on previously untouched land. The model’s strength lies in its ability to scale, to mobilize massive infrastructure rapidly, and to align state power with capital flow. But it is not without flaws. Long-term housing security remains an issue, as land use rights are time-limited and subject to renewal decisions. Additionally, the heavy reliance on land finance has led to overbuilding in some areas, and the top-down nature of planning limits public participation or adaptability. Despite these issues, China’s SEZ strategy shows that state-directed greenfield development can be both fast and flexible when land is used as an economic tool, not just as a regulatory asset.

Reflecting on China’s Model in Comparative Context—China’s success with greenfield development through SEZs is particularly illuminating when viewed alongside the trajectories of the U.S., Dubai, and Egypt. Unlike the U.S., where land was privatized and dispersed to individuals to foster bottom-up expansion, China maintained state ownership but created a quasi-market through long-term land-use rights and intense local government incentivization. It’s a model where the state retains control—but delegates execution. Local governments, especially in SEZs, have the autonomy to act entrepreneurially: leasing land, capturing land-value gains, and reinvesting in infrastructure at breakneck speed. Unlike Dubai, where vision and branding are tightly centralized and elite-driven, China’s model is structurally decentralized within a unitary state. Each municipality functions like a growth-seeking corporation—offering incentives, streamlining approval processes, and competing for talent and investment. While Dubai’s administrative agility comes from top-down cohesion, China achieves scale through horizontal competition and fiscal motivation at the local level.

For Egypt, China’s approach reveals what centralization could look like if paired with execution capacity, fiscal alignment, and local autonomy. Egypt, like China, has vast state-owned land. But the comparison exposes the deeper issue: Egypt’s state does not empower local authorities with the financial tools or governance flexibility to act as engines of development. Instead of leasing land to finance infrastructure and attract investment, land often sits idle or trapped in fragmented jurisdictions. Municipalities lack both the autonomy and incentives to mobilize land as an economic asset. Additionally, China’s coordinated rollout of infrastructure, policy, and economic strategy within a given zone stands in stark contrast to Egypt’s pattern of building “new cities” without first creating enabling conditions. In China, the tax policy, industrial roadmap, and transit network are launched in tandem. In Egypt, these elements are often disjointed, misaligned with demand, or delayed by bureaucratic drag. Finally, where China has normalized the idea of land-use rights as tradable instruments, Egypt still lacks secure, transferable tenure for most of its land—especially in desert areas. This legal ambiguity suppresses investment, limits land liquidity, and drives informal development instead of organized expansion. In short, China’s SEZ approach demonstrates that central control does not have to mean stagnation. When paired with devolved authority, fiscal incentives, and clear legal mechanisms, state-led development can be fast, scalable, and investment-friendly—a lesson that Egypt, and others, have yet to fully absorb.

Rwanda’s People-Centered Planning: Building Sustainable Cities Through Policy and Participation

Rwanda stands out in the greenfield development conversation not for its scale or its skyline, but for its principled, inclusive, and future-focused approach. As one of Africa’s smallest and most densely populated countries, Rwanda has limited space but ambitious goals. Rather than pursuing speculative mega-projects or top-down cities, Rwanda has developed a national urbanization strategy that centers around citizen involvement, sustainability, and regional equity. All land in Rwanda is held under state custodianship, but individuals and institutions can obtain long-term leases—up to 99 years—that provide the security needed for investment and homebuilding. The government has used this structure to design and implement greenfield projects that serve broad public goals. One of the flagship efforts is Bugesera New City, a planned urban center located near a major new international airport. The city incorporates mixed-use zoning, public transit, renewable energy integration, and ample green space—not just as design features but as core urban priorities. Similarly, Kigali Innovation City, another major greenfield initiative, aims to become a hub for digital enterprise, research, and education, supported by strong public-private partnerships.

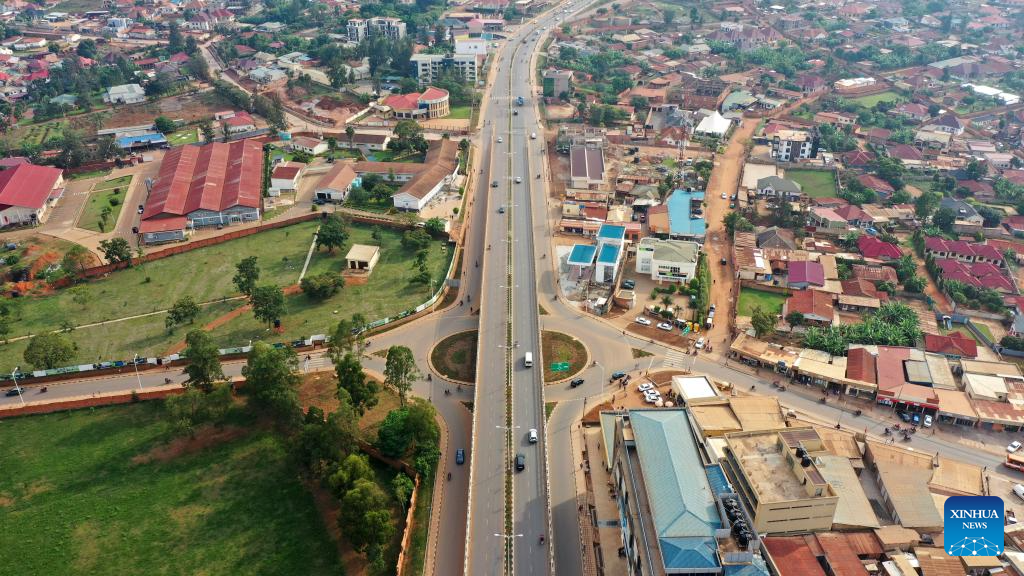

Kigali and Rwanda’s Urban Ambition—This aerial view of Kigali captures more than upgraded roads—it reflects a country intentionally reshaping its urban future. Rwanda stands out not for the size of its megaprojects, but for the coherence of its vision. With a population of 13.5 million packed into just 26,000 square kilometers, Rwanda is Africa’s most densely populated mainland country. Yet rather than sprawling unchecked, it has developed a National Urbanization Policy that promotes balanced regional growth, participatory planning, and environmental sustainability. All land is held under state custodianship, but 99-year leases give citizens and investors the security to build. In Kigali, this has translated into an estimated $4.5 billion urban economy with per capita GDP around $3,500—ambitious, but far from its Vision 2050 target of over $12,000. Flagship projects like Bugesera New City, adjacent to the new international airport, and Kigali Innovation City, a tech and education hub, showcase smart zoning, renewable energy, and inclusive design. Still, a word of caution is warranted: the infrastructure is ahead of job creation in many areas, and bridging the gap between high-level plans and widespread livelihood gains remains the country’s next great urban challenge.

What makes Rwanda’s approach particularly distinctive is the emphasis on participatory planning. Community input is not only encouraged but institutionalized in urban policy, helping to avoid displacement, reduce resistance, and tailor services to actual needs. This model doesn’t just focus on what gets built but how—and for whom. Urban plans align with Vision 2050, the country’s long-term development roadmap, and are closely coordinated with decentralization policies that empower local governments. This ensures that growth is not just Kigali-centric but balanced across the country. Rwanda’s method is slower than models like China or Dubai, but it is more inclusive, context-aware, and adaptable to lower-income settings. There are limitations: funding is often dependent on donor partnerships, and the scale of implementation remains modest. But the values embedded in Rwanda’s model—resilience, equity, and sustainability—make it a powerful alternative for countries that seek development without dispossession, and progress without exclusion.

Reflecting on Rwanda’s Model in Global Context—Rwanda’s greenfield strategy introduces a compelling contrast to the dominant models seen in the U.S., Dubai, China, and Egypt. Unlike the U.S., where development emerged from private land ownership and speculative settlement, Rwanda maintains state custodianship over land—but uses it to ensure long-term tenure, not to concentrate control. Where China and Dubai rely on top-down planning and high-speed execution, Rwanda’s approach is deliberative, participatory, and anchored in community consent. And unlike Egypt, which has struggled to align its central planning with citizen needs or local execution, Rwanda has embedded decentralization and local empowerment at the core of its urban strategy.

Rwanda’s model is not fueled by mass capital flows or global speculation, but by policy discipline, coordination, and social trust. Its strength lies in linking urban development with national planning frameworks (like Vision 2050), environmental stewardship, and democratic accountability. The result is slower-paced growth, but with far greater alignment between what is built and what is needed. Where Dubai and China offer visions of rapid transformation driven by infrastructure and investment, Rwanda reminds us that inclusive governance and long-term resilience are just as foundational—especially in contexts where resources are limited and social cohesion is paramount. It demonstrates that you don’t need petro-dollars, hyper-centralization, or hyper-liberal markets to plan and deliver meaningful urban expansion. Perhaps most importantly, Rwanda’s model offers a direct counterpoint to Egypt’s. Both are centralized states with strong executive branches, but while Egypt has often bypassed community voices and entrenched bureaucratic complexity, Rwanda has institutionalized participation, streamlined land policy, and empowered localities. It shows that central government control does not inherently preclude inclusion—it depends on how authority is exercised and shared. In short, Rwanda’s approach may not produce skylines that rival Dubai’s, or megazones that match China’s—but it offers a blueprint for countries seeking sustainable, just, and locally grounded urban futures. It’s a model that places dignity before scale and governance before glamour.

Still, Rwanda’s approach is relatively recent and modest in scale, and its long-term success remains to be seen. Projects like Bugesera New City and Kigali Innovation City reflect strong intent and policy clarity, but they are in early phases of implementation and have yet to demonstrate large-scale impact or replication across the country. Ultimately, Rwanda’s value may lie less in what it has already achieved, and more in what it is trying to prove: that development can be deliberate rather than hasty, inclusive rather than imposed, and sustainable even when speed and scale are sacrificed.

India’s Equitable Expansion: Land Pooling and Infrastructure as Tools for Inclusive Urban Growth

India’s approach to greenfield development reflects the complexity of governing a vast, diverse democracy with deep-rooted land rights and explosive urban demand. Instead of forcibly acquiring land for new cities—an approach that often leads to displacement, protest, and legal gridlock—India has pioneered a land pooling model that emphasizes equity, local participation, and infrastructure-first development. This system allows farmers and landowners to voluntarily contribute parcels of land toward a larger development project. In return, they receive a smaller piece of developed land, now equipped with roads, utilities, and access to markets, which is far more valuable than their original plots. The result is a shared-upside model, where the government acts as planner and facilitator rather than expropriator, and citizens become stakeholders in the new urban future. Two of India’s most prominent examples of greenfield development under this model are the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC) and GIFT City in Gujarat. The DMIC is a massive 1,500-kilometer economic zone that connects India’s capital with its financial hub via a spine of industrial, residential, and logistical hubs. GIFT City, by contrast, is a smaller but highly strategic smart financial center being developed on pooled land to attract fintech firms, international banks, and startups. In both cases, the government invested first in infrastructure—highways, transit, utilities, and digital connectivity—before inviting private developers and businesses to build. This sequencing is critical: it raises land values, builds investor confidence, and ensures that development is not speculative but service-ready from the outset.

Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor: Infrastructure-First, Stakeholder-Led Urbanization at Scale—Spanning over 1,483 kilometers and backed by $90 billion in investment, the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC) is one of the world’s most ambitious infrastructure and greenfield development initiatives. Designed to connect India’s political and financial capitals, the corridor cuts across six states and incorporates nine mega industrial zones, six airports, three ports, and a 4,000 MW power plant. But beyond scale, DMIC represents a distinct model: infrastructure-first, equity-led, and deeply grounded in democratic land governance. Rather than rely on forced acquisition, India adopted a land pooling mechanism—transforming rural landowners into equity participants who retain upgraded, serviced plots with significantly higher market value. By aligning infrastructure investment with shared citizen upside, India has created an urban development strategy that is both inclusive and investor-ready. The corridor aims to triple industrial output, double employment, and quadruple exports within five years, all while anchoring new urban nodes in logistics, trade, and manufacturing. The DMIC is not just about moving goods—it is about reimagining land value creation, industrial productivity, and sustainable urban growth in one of the world’s most complex democratic contexts.

What sets India’s model apart is its sensitivity to rural livelihoods and democratic rights. By avoiding large-scale displacement and giving former landowners a stake in the transformed landscape, it reduces resistance and fosters local buy-in. Farmers may lose land area, but they gain formal property in urbanized environments—complete with title deeds, access to finance, and vastly increased earning potential. It’s a model that tries to balance the need for rapid urban growth with the principles of social justice and participatory governance. Of course, the model is not without challenges. Implementation requires careful cadastral mapping, transparent valuation mechanisms, and long-term coordination between multiple layers of government. Delays are common, and legal disputes can arise over compensation or entitlement. In addition, while the model protects landowners, it may not always address the needs of landless laborers or urban migrants. Yet, in a country where land politics are intensely sensitive, India’s land pooling strategy represents one of the most politically viable and socially inclusive frameworks for greenfield development. As Indian cities continue to expand outward, this model is likely to gain more traction—not only as a solution to land acquisition challenges, but as a blueprint for building equitable cities from scratch. It offers a clear alternative to top-down or market-exclusive models, and it reflects a deeper truth: in democracies, development must be negotiated, not imposed.

Comparative Reflection: India’s Negotiated Urbanism—India’s land pooling strategy sits at a unique crossroads between market economics and democratic negotiation, offering a contrast to the more centralized or elite-led approaches seen elsewhere. Unlike Dubai and China—where land is controlled by the state and development decisions flow top-down—India builds through consensus, legal process, and local buy-in. This makes the process messier, slower, and harder to replicate at scale, but also more politically durable and socially equitable. Where Egypt struggled under rigid central planning and an unwillingness to devolve meaningful control, India has attempted to navigate land politics by creating a shared-upside model that keeps landowners invested in the urban future.

India also diverges from the U.S. model, where individual ownership and market freedom drove expansion but often at the expense of coordinated infrastructure or equitable distribution. India’s sequencing—build infrastructure first, then develop—reflects a more deliberate state role in shaping markets rather than just unleashing them. But perhaps the most meaningful comparison is with Rwanda. Both countries use long-term leases, prioritize infrastructure, and embed urbanization within national development goals. Yet Rwanda’s approach is far more centralized and technocratic, while India’s is pluralistic and adaptive, contending with a larger, more vocal set of stakeholders and legal traditions. Rwanda can execute through policy alignment and tight institutional control; India must govern through legal consensus and democratic friction. This makes India’s model harder to implement, but also more transferrable to other democratic contexts where displacement is politically sensitive and top-down urbanism is no longer viable. It is a model for places where urban growth must be negotiated—not imposed—and where fairness is not just a principle, but a prerequisite for stability.

Despite its ancient history as one of the most fertile and productive agricultural zones in the world, Egypt’s Nile Delta lacks a coherent corridor for its dominant economic sector—agriculture. For millennia, the Delta has sustained civilizations with its rich alluvial soil and favorable climate, feeding millions and anchoring the country's economy. Yet unlike industrial or commercial sectors that benefit from spatially integrated corridors—such as roads, logistics hubs, and clustered processing zones—agriculture in the Delta remains fragmented and inefficient. Fields are splintered into micro-plots due to generational inheritance, infrastructure is piecemeal, and there is no consolidated system for production, distribution, or value addition. This stands in stark contrast to how other sectors, or even agriculture in countries like India and Morocco, have been reorganized into high-productivity corridors. The Delta’s potential remains vast, but its structure—physically and institutionally—has not kept pace with modern demands for scale, connectivity, and resilience. Egypt lost around 90,000 to 120,000 hectares (215,000 to 300,000 feddans) of agricultural land between 1980 and 2020 due to urban sprawl, especially in the Delta. Land is lost at a rate of approximately 20,000–30,000 feddans per year, driven by informal housing and infrastructure expansion. Productivity losses from fragmentation are estimated to be 20–30% in key crops like wheat and maize, due to inefficient water usage, overlapping irrigation channels, and reduced economies of scale.

If Egypt were to adopt a land pooling model similar to India’s—but apply it to agriculture rather than urban development—the Nile Delta could be transformed into a high-efficiency agricultural production corridor. One of the Delta’s most urgent challenges is land fragmentation, with average farm holdings falling below 1 feddan (approximately 0.4 hectares). This severely limits the adoption of modern agricultural practices, making mechanization, efficient irrigation, and market integration difficult or unviable. Now imagine if just 10% of the Delta’s 2.4 million hectares—about 240,000 hectares—were voluntarily pooled through a land consolidation scheme. Instead of displacing farmers, this model would allow smallholders to retain shares or receive equivalent serviced plots within larger, cooperative-scale farms. These farms could be equipped with precision irrigation systems, offer shared machinery services, and provide access to digital extension tools and centralized cold chains. By scaling up in this way, yields for cereals could increase from the current 2–4 tons per hectare to global benchmarks of 6–8 tons per hectare. The result would be a significant boost to farmer incomes, more efficient water use, and new job creation along the agricultural value chain. Most critically, this model could reverse decades of unplanned fragmentation not by removing people from their land, but by giving them a sustainable stake in a modernized farming future. A study by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) estimated that consolidating land could improve crop yields by 25–40%, depending on crop and location.

Corridor Thinking over Fragmentation—India’s DMIC power lies in organizing dispersed assets—industrial zones, logistics hubs, power plants—into a strategically linked corridor. The Delta, though agriculturally rich, suffers from spatial fragmentation. Applying corridor logic to agriculture would mean zoning areas for high-value crops, mechanization, processing, cold storage, and export logistics, all connected via integrated infrastructure. This would counter the inefficiencies of smallholder fragmentation. A defining principle of DMIC is that infrastructure precedes development—rail, roads, water, and energy were built before inviting businesses. In the Delta, prioritizing water-efficient irrigation, rural roads, solar cold chains, and processing centers before individual farm subsidies could multiply productivity and attract agro-investment. Instead of expropriating farmland, DMIC uses land pooling: landowners contribute parcels and receive back smaller but serviced plots with higher value. The Delta could apply a voluntary land consolidation model, enabling modern farming while preserving ownership, boosting farmer incomes, and creating economies of scale. DMIC functions through special purpose vehicles (SPVs) with intergovernmental coordination and private sector roles. The Delta’s agricultural revival would require a similar corridor authority to align ministries, local governments, and private investors around shared outcomes, avoiding institutional silos. Also, DMIC includes vocational hubs and skilling programs for industrial workers. A Delta corridor could embed agri-skilling centers focused on smart irrigation, regenerative farming, agri-tech, and food processing, preparing youth for a modern agricultural economy.

Ethiopia’s Industrial Pathway: Building Economic Zones Before Cities to Create Jobs and Attract Investment

Ethiopia’s approach to greenfield development is driven by industrialization first, urbanization second. Rather than beginning with housing, civic services, or organically expanding neighborhoods, Ethiopia has focused on developing employment-focused industrial parks across the country. These zones are designed to attract manufacturers, create jobs, and stimulate export growth by transforming undeveloped land into specialized economic enclaves. The strategy is heavily state-led, often supported by development finance institutions and foreign partners, and framed around Ethiopia’s national vision of becoming a low-cost manufacturing hub within Africa. The most prominent example of this model is the Hawassa Industrial Park, located in southern Ethiopia. Built from scratch, the park is dedicated largely to the textile and garment industries, with tenants including major international brands. The park is equipped with essential infrastructure—power, water, transport access, and factory-ready space—and was constructed rapidly with support from foreign development banks and Chinese contractors. It has become a symbol of Ethiopia’s ambitions: to move beyond subsistence agriculture and informal trade, and to integrate into global manufacturing supply chains through purpose-built zones.

Inside Hawassa Industrial Park—Ethiopia’s flagship industrial zone and a cornerstone of its “build jobs first” development strategy. Spanning over 300 hectares and hosting more than 52 factory sheds, the park employs nearly 30,000 workers, the majority of whom are women under 30. It is dedicated primarily to textile and garment exports, with global brands like PVH and H&M among its tenants. Located 275 kilometers south of Addis Ababa, the park benefits from fast-track logistics, a dedicated eco-industrial water treatment plant, and zero liquid discharge systems. Completed in under a year with financing from the Ethiopian government and development banks, and constructed by Chinese firms, Hawassa is part of a broader network of 13 state-led industrial parks across Ethiopia. This model—industrialization before urbanization—contrasts sharply with speculative new city approaches. Instead of leading with housing or civic services, Ethiopia’s strategy anchors urban growth around employment, positioning the country as Africa’s low-cost manufacturing hub. While questions remain about long-term sustainability and value-chain integration, Hawassa exemplifies a state-driven, export-oriented approach to greenfield development aimed at transforming land into labor opportunity.

What defines Ethiopia’s model is its focus on productivity rather than population. Unlike the U.S. homestead system or India’s land pooling strategy, Ethiopia’s greenfield development is not driven by citizen settlement or decentralized ownership. Instead, it is about creating employment clusters that can absorb large numbers of rural and underemployed workers into formal wage labor. The parks are established in areas with strategic logistics potential or demographic need, and their development is led by federal agencies like the Ethiopian Investment Commission. Once operational, the state often supplements the industrial core with public housing or dormitories to accommodate workers, aiming to prevent the growth of informal slums around the zones. This model has clear strengths. It enables the government to channel foreign investment into specific sectors, especially those with labor-intensive value chains. It also allows for tight control over land use and zoning, reducing conflict and ensuring environmental standards are met—at least in theory. For international partners, the model provides a focused and measurable return: jobs created, exports increased, factories opened.

However, the Ethiopian approach also has limitations. Because land remains under state ownership and is allocated through central agencies, citizens lack secure, tradable property rights, which can limit long-term investment and upward mobility. The model also does not produce full-fledged cities—just economic zones with limited amenities beyond production. Social services, education, healthcare, and broader urban infrastructure are often underdeveloped. In many cases, workers live in tightly controlled housing with little path to ownership or community building. Furthermore, the system is highly dependent on external financing and foreign demand, making it vulnerable to global supply chain shocks, shifting trade policies, and geopolitical shifts. Despite these challenges, Ethiopia’s model shows how greenfield development can be productively deployed in low-income contexts with limited private capital. When the goal is job creation, not urban sprawl, centralized planning can deliver targeted outcomes quickly. But for this model to evolve into a true engine of national development, it must be paired with broader land reform, civic infrastructure, and a shift toward more inclusive city-building over time. Until then, Ethiopia’s industrial parks will remain islands of productivity surrounded by underdeveloped territory, waiting for the next stage of urban evolution.

Comparative Reflection: Ethiopia and the Limits of Job-First Urbanization—Ethiopia’s job-first strategy for greenfield development diverges sharply from the models seen in Dubai or China, where land is monetized and cities are built as complete economic ecosystems. In contrast, Ethiopia’s industrial parks prioritize production over population, creating enclaves of employment without the supporting urban infrastructure or civic life that make cities self-sustaining. This differs fundamentally from Dubai’s infrastructure-first luxury urbanism, which builds value through branding, real estate speculation, and global connectivity, or China’s SEZs, which pair industrial development with massive public investment and residential expansion. It also presents a stark contrast to India’s land pooling model, where development is negotiated with landowners and oriented toward inclusive urban transformation. Egypt, while similarly centralized in approach, has often undermined productivity by redistributing cultivated land inefficiently or placing settlement ahead of infrastructure—effectively inverting Ethiopia’s prioritization. Rwanda, like Ethiopia, also pursues state-led planning, but embeds it in community participation and broader service delivery, making its greenfield efforts more socially grounded. Meanwhile, the U.S. model, driven by speculative private settlement and market logic, lacks the discipline of Ethiopia’s directed industrial zones but offers greater flexibility, property rights, and path to ownership.

What Ethiopia reveals is the strength—and the danger—of singular purpose in greenfield development. Its zones succeed as employment machines but struggle to evolve into cities. Without institutionalized mechanisms for housing rights, social mobility, or democratic participation, they risk reproducing the very rural exclusion they are meant to escape. And while labor is cheap—like in Egypt—and the state can move decisively, the absence of broader urban vision limits the sustainability of the model. Ethiopia’s experience offers an important reminder: creating jobs is critical, but it cannot substitute for city-making. In the long term, industrial parks must not remain isolated islands of productivity—they must be woven into the fabric of inclusive, livable urban futures.

Beyond Models: What Greenfield Development Teaches Us About Power, Policy, and Participation

After examining these global experiments—from Dubai’s infrastructure-led grandeur to India’s negotiated land pooling, and from Ethiopia’s job-first industrial parks to Rwanda’s inclusive planning—a deeper insight emerges: no single model succeeds without resolving the underlying question of who land is for. Whether land is treated as a public good, a commodity, a tool for productivity, or a site of social inclusion profoundly shapes what kind of city will follow. Some models deliver speed and scale—China and Dubai excel here—but often sacrifice inclusion or long-term adaptability. Others, like Rwanda or India, prioritize equity and participation but face hurdles in financing and speed. Egypt’s challenge lies not in the absence of models to learn from, but in the failure to resolve contradictions within its own: between control and responsiveness, infrastructure and settlement, vision and implementation.

The global lessons point to four critical ingredients that matter more than any one blueprint.

Clarity of Land Rights—At the heart of every successful greenfield development is the question of ownership—who has the right to use, invest in, sell, or build on land. Clarity of land rights does not simply mean privatization; it means creating systems where individuals, businesses, and institutions can act with confidence. In the U.S., the Homestead Acts granted title to land and unlocked generational wealth. In India, land pooling converted informal farmers into formal stakeholders. Even in China—where the state owns all land—long-term leases function as de facto ownership, creating a tradable asset base. By contrast, in countries like Egypt or Ethiopia, where land remains under tight state control and is often allocated via opaque mechanisms, individuals and investors are left in limbo. This undermines trust, limits private capital mobilization, and slows down long-term planning. Clear, enforceable rights—whether through private titles, long leases, or communal frameworks—allow land to act as collateral, to attract infrastructure investment, and to anchor human settlement. Without this clarity, development either stalls or proceeds through informal channels. Ultimately, legal certainty around land rights is the precondition for every other ingredient in successful greenfield development—it turns land from a regulatory headache into an economic platform.

Sequenced Infrastructure Investment—Infrastructure is not just the support system of a city—it is the spark that makes land valuable. Dubai’s entire urban growth model is premised on building roads, power, water, and connectivity before private investors show up. This anticipatory approach flips the conventional logic: instead of waiting for congestion or demand to justify infrastructure, it creates demand through infrastructure. In the U.S., westward expansion followed railroad tracks; in China’s SEZs, ports and highways were built before factories opened. By contrast, in places like Egypt or many African contexts, land is often allocated or sold before it is serviced, leading to speculative hoarding, unlivable plots, and informal settlements. Infrastructure-first development ensures that land is not just accessible—but economically functional. It allows planners to shape growth rather than chase it, enables land value capture, and supports integrated zoning. It also sends a powerful signal to investors: this is a place with momentum, services, and a future. Sequencing is crucial. Build infrastructure too late, and you institutionalize inequality and inefficiency. Build it too early, and you risk white elephants. But when done right—strategically, and with long-term coordination—it transforms dirt into opportunity, and plans into reality.

Governance Agility—Speed and coordination are often more important than centralization. Dubai shows how a streamlined, top-down governance model can cut through red tape and deliver massive results quickly. But governance agility does not require autocracy—it requires alignment. In India, land pooling is made possible by cross-tier coordination: local governments engage landowners, state governments provide legal frameworks, and central agencies fund infrastructure. In China, municipalities act like corporations, aligning budgetary powers with planning authority. Rwanda uses a decentralized system that still follows a unified national vision. Egypt, by contrast, struggles not because it is too centralized, but because it is not agile: decisions are fragmented, permissions are slow, and there is often a gap between planning and execution. Governance agility means collapsing silos—between transport and housing, between legal frameworks and economic strategies—and giving empowered institutions the authority to act. It also means having feedback mechanisms to adapt and course-correct when conditions change. Agility is not chaos; it’s flexibility with direction. For greenfield development, this is the difference between static masterplans and living cities. Without it, even the best land policies will falter under the weight of slow, uncoordinated implementation.

Meaningful Participation—Participation isn’t just about fairness—it’s about functionality. Greenfield development that ignores people’s needs, rights, or voices will either be resisted or fail to serve its purpose. India’s land pooling succeeds because it turns landowners into partners, not victims. Rwanda integrates citizen input into national planning frameworks, building legitimacy and long-term buy-in. In contrast, many top-down models—however efficient—risk producing exclusionary, elite-driven enclaves. Dubai’s real estate boom works for investors, but not always for middle-class residents or low-income workers. Ethiopia’s industrial parks create jobs, but little community. Egypt’s planning too often excludes the very people who will inhabit or use new spaces. Participation can take many forms—consultation, co-ownership, shared upside, public engagement—but it must be embedded in process, not just promised on paper. It ensures that infrastructure matches real demand, that displacement is avoided or mitigated, and that citizens have a stake in protecting and improving their environment. It also reduces conflict, boosts legitimacy, and brings local knowledge into planning. In greenfield contexts, where blank-slate thinking often dominates, participation is the anchor that ensures cities are not just built—but lived in, respected, and sustained.

Successful greenfield development is not about copying models but aligning land rights, infrastructure, governance, and participation to build inclusive, adaptable, and future-ready cities that serve both people and economies.

At OHK, we help governments, development institutions, and private sector leaders navigate the complex trade-offs of land policy, infrastructure investment, and governance reform. Our expertise lies in translating spatial and economic strategies into actionable models that quantify long-term impacts—whether it’s unlocking land value, forecasting the returns on infrastructure-first development, or benchmarking policy outcomes against global peers. We combine deep regional knowledge with robust international frameworks to identify opportunity costs, structural bottlenecks, and scalable solutions. From greenfield city planning to national growth diagnostics, our work equips decision-makers with the clarity, comparability, and foresight needed to design inclusive, future-ready development strategies. Contact OHK to learn how our economic modeling capabilities can help you make smarter, data-driven decisions for the future.