The Infrastructure Gap in Carbon Accounting: Why Carbon Software Platforms Digitize Workflows Instead of Building Systems of Trust

Three Structural Lenses: Software Architecture, National Market Implementation, and Capital Market Infrastructure

This illustration shows how carbon markets are shaped by three interconnected layers—digital software systems translating data into action, national institutions turning climate policy into real-world implementation, and financial market infrastructure scaling climate outcomes through capital, governance, and risk management—highlighting that true credibility depends not on any single layer, but on how all three work together as a unified system of trust.

This article, Part III, forms the third part of a four-part series examining the evolution of carbon markets and the digital foundations of climate accounting. After tracing the origins of carbon market design and diagnosing today’s fragmented ecosystem, this installment focuses on the shortcomings of current carbon technology platforms, highlighting why workflow automation has failed to create credible systems of trust. The final article presents OHK’s full-stack model for building resilient, transparent carbon market infrastructure and is not shared publicly. Refer to Part I here and Part II here.

In essence, this is a key part of OHK’s structural trilogy on carbon:

• Part I — Carbon Markets: Incentive architecture and economic distortion

• Part II — Carbon Accounting: Measurement systems, technology scaling distortions, digital MRV, and modeled emissions

• Part III — Carbon Infrastructure: Software architecture built around processes rather than systems, institutional governance design, and programmable integrity

Reading Time: 45 min.

All illustrations are copyrighted and may not be used, reproduced, or distributed without prior written permission.

Summary: Part III explains why most carbon technology platforms treat climate accounting as a reporting and project-management problem rather than an institutional infrastructure challenge. It contrasts surface-level workflow automation with the deeper requirements of verifiable data pipelines, tamper-resistant audit systems, methodology governance, and registry-level interoperability. By examining common architectural shortcomings, the article shows how many platforms inadvertently reproduce the same integrity risks present in traditional carbon markets, simply in digital form, and argues that credibility requires systemic redesign rather than incremental software enhancements. The overall arc is: platform layers → reporting fallacy → procedural verification → fragmented governance → dashboards vs operating systems → institutional ownership → what true infrastructure requires → conclusion.

The Software Architecture of Carbon Markets

This installment builds directly on the structural diagnosis established earlier: that digital tools dramatically increased speed, scale, and visibility across carbon markets without resolving the deeper integrity challenges embedded in market design. While the previous analysis examined how technology amplified ecosystem-level fragmentation and trust erosion, this installment shifts focus to the architecture of carbon software itself revealing how most platforms were built to optimize workflows rather than to engineer systems of trust. What follows does not revisit the broader credibility crisis, but instead dissects the technical and institutional foundations that produced it. By breaking down modern carbon platforms into their core architectural layers, examining the reporting-centric logic that dominates today’s tools, distinguishing dashboards from true market operating systems, and analyzing how governance fragmentation became embedded directly into software design, this section exposes why digitization improved execution without transforming integrity. Together, these insights move from ecosystem diagnosis to infrastructure diagnosis — explaining not just that trust eroded as markets scaled, but precisely how software architecture and institutional design choices made that outcome structurally inevitable.

How Carbon Platforms Are Typically Built: Digitizing Process Without Redesigning Systems

This illustration shows carbon market technology as a high-speed assembly line, where documents, approvals, and automated calculations move efficiently through digital workflows while deeper questions of environmental integrity remain outside the system, highlighting how today’s platforms optimize process and throughput without redesigning the underlying architecture of trust.

Most modern carbon software platforms did not emerge as infrastructure blueprints. They emerged as responses to operational bottlenecks. From the market perspective, project developers needed faster documentation cycles, automated emissions calculations, supplier engagement tools, and simplified reporting to reduce transaction costs and accelerate credit issuance. Corporations under net-zero pressure required systems capable of aggregating Scope 1, 2, and 3 data across thousands of suppliers and geographies. From the policy infrastructure perspective, regulators and standards bodies needed standardized digital templates, structured submissions, registry automation, and improved administrative throughput to manage rapidly increasing credit volumes and corporate disclosure requirements under regimes such as CSRD in the European Union and emerging SEC climate disclosure rules in the United States.

This dual pressure led not to systemic redesign but to workflow digitization. This resulted in a common platform architecture focused on: (i) Data input dashboards for project metrics and corporate emissions reporting; (ii) Project management workflows to guide documentation, approvals, and audits; (iii) Automated calculation engines to apply methodology formulas at scale; (iv) Digital registries to issue, transfer, and retire credits; and (v) Reporting automation aligned with compliance and disclosure frameworks. Each of these components can be clearly observed across today’s carbon software ecosystem.

(i) Data Input Dashboards: Structured Interfaces for Emissions Reporting: Platforms such as Watershed, Persefoni, Sweep, Normative, Plan A, and Sphera provide centralized dashboards that aggregate energy usage, procurement spend, travel data, logistics records, and supplier inputs into emissions inventories. In practice, this is visible in multinational corporations such as large consumer goods companies and technology firms integrating Watershed or Persefoni into their ERP systems to automate Scope 1–3 calculations. Supplier portals allow vendors to upload emissions data directly, replacing spreadsheet exchanges with structured digital submissions. From a policy perspective, these dashboards enable standardized data formats that regulators can interpret more easily. Under the EU’s CSRD regime, companies increasingly rely on these systems to produce structured ESG disclosures. From a market perspective, dashboards allow internal sustainability teams to visualize footprint hotspots and manage reduction targets dynamically. However, in most enterprise implementations, between 60 percent and 90 percent of Scope 3 emissions remain estimated using emissions factors rather than measured primary data.

The interface digitizes inputs but does not guarantee input accuracy.

(ii) Project Management Workflows: Digitizing Documentation, Approvals, and Verification Chains:

Platforms such as Verra Registry interfaces, Gold Standard Impact Registry tools, Patch project management modules, Sylvera project pipelines, and numerous bespoke MRV SaaS platforms structure the entire lifecycle of carbon projects through step-by-step digital workflows — from project design documents and baseline submissions to monitoring reports, verifier reviews, and credit issuance approvals. In practice, this is visible across voluntary market project developers in forestry, cookstoves, renewable energy, and soil carbon who now manage dozens to hundreds of projects simultaneously through cloud-based workflow systems rather than physical documentation. For example, large nature-based solution developers operating across Latin America and Africa use centralized platforms to upload satellite evidence, monitoring reports, and auditor feedback in standardized digital sequences that mirror registry approval logic. From a policy perspective, these workflows improve administrative consistency, traceability, and audit trail organization, making it easier for standards bodies to manage surging project volumes. From a market perspective, they dramatically reduce time-to-issuance, allowing credits to reach buyers months faster than under legacy paper-based systems. However, what is fundamentally being digitized is the process of approval, not the substance of integrity — baseline assumptions, additionality narratives, and methodological choices are still accepted largely as submitted, meaning that workflow automation accelerates throughput without independently testing economic realism, systemic over-crediting patterns, or long-term climate impact.

Process discipline improved. Assumption discipline did not.

(iii) Automated Calculation Engines: Scaling Methodologies Through Software Logic:

Modern carbon platforms embed approved methodologies directly into software engines that automatically apply baseline formulas, leakage factors, permanence buffers, emissions coefficients, and projection models at scale. Systems used by both project developers and corporate accounting platforms now process thousands of emissions calculations in seconds — something that once required months of spreadsheet modeling. In practice, this is visible in renewable energy offset platforms that automatically compute avoided emissions using grid emission factors, in forestry platforms that estimate biomass change through AI-assisted remote sensing models, and in industrial MRV systems that convert energy and production data into CO₂e outputs continuously. Many nature-based solution platforms now run machine-learning models to simulate forest growth, avoided deforestation scenarios, and carbon sequestration trajectories over 20–40 year crediting periods. From a policy perspective, automated engines provide methodological consistency and scalability, allowing standards bodies to process exponentially more projects than human review alone could manage. From a market perspective, they slash transaction costs and enable rapid project expansion across geographies. Yet in most implementations, these engines still rely on modeled counterfactuals rather than verified physical outcomes, and once encoded into software, methodological biases become harder to detect, challenge, or stress-test systemically. In effect, assumptions that were once manually manipulated in spreadsheets are now industrialized through code — meaning that baseline inflation, optimistic growth projections, and subjective additionality logic are no longer slow risks, but fast ones.

Methodology scaled. Economic plausibility remained external.

(iv) Digital Registries: High-Speed Asset Tracking Without Scientific Verification Layers:

Digital registries such as Verra’s Registry, Gold Standard Impact Registry, American Carbon Registry, Climate Action Reserve systems, national ETS registries across the EU and some Asian compliance markets, and newer blockchain-linked tokenization overlays such as Toucan and KlimaDAO that mirror credits issued through traditional registries now issue, transfer, and retire billions of credits annually through automated ledger systems. In practice, this is visible in the EU Emissions Trading System where allowance ownership updates in near real time across regulated firms, and in voluntary markets where corporate buyers retire credits instantly through web-based interfaces rather than manual certificate processes. From a policy perspective, registries provide essential safeguards against double counting, enable market oversight, and support compliance enforcement by maintaining formal ownership records. From a market perspective, they dramatically increase liquidity, transaction speed, and transparency of asset flows, allowing carbon credits to function like modern financial instruments rather than slow administrative certificates. However, registries largely verify ownership, not environmental reality. They assume that credits entering the system are valid because upstream methodologies and audits approved them. There are no embedded scientific plausibility engines, cross-project baseline comparisons, or continuous performance verification layers inside registry infrastructure itself. Once a credit is issued, the registry treats it as environmentally equivalent to any other within that standard — regardless of underlying integrity variance. In effect, registries solved financial settlement but not climate verification, mirroring early stock exchanges before modern risk management systems existed.

Transaction certainty improved. Climate certainty did not.

(v) Reporting Automation and Disclosure Systems: Compliance at Speed Without Integrity Intelligence:

Corporate carbon management platforms such as Persefoni, Watershed, Sweep, Normative, Plan A, Salesforce Net Zero Cloud, Microsoft Sustainability Manager, and Sphera now automate emissions reporting across Scope 1, 2, and 3, linking operational data directly into regulatory disclosures, internal dashboards, and ESG reporting pipelines. In practice, this is visible across large financial institutions, multinational manufacturers, and consumer brands integrating these platforms into ERP systems to automatically populate sustainability reports aligned with frameworks such as the GHG Protocol, TCFD, and the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive. From a policy perspective, these tools improve consistency, audit readiness, and regulatory transparency by standardizing emissions accounting across thousands of firms. From a market perspective, they enable real-time footprint management, supplier engagement programs, and dynamic decarbonization planning that would be impossible through manual spreadsheets. Yet most platforms still rely heavily on emissions factor estimation rather than measured primary data, particularly across Scope 3 supply chains where up to 80–95 percent of emissions are typically modeled. Reporting automation therefore improves disclosure speed and visual clarity while perpetuating the same assumption-based accounting foundations. The systems excel at organizing climate data—but they rarely verify whether that data reflects real-world emissions outcomes. Integrity remains external, episodic, and procedural.

Disclosure accelerated. Verification architecture remained largely procedural.

Structural Synthesis—Efficiency Everywhere, Trust Nowhere Embedded: Across all five architectural layers—dashboards, workflows, calculation engines, registries, and reporting automation—modern carbon platforms have achieved extraordinary operational efficiency. Project pipelines scale faster. Corporate disclosures improve. Credit issuance accelerates. Transaction costs fall dramatically. From the policy perspective, it enabled administrative scalability and regulatory visibility that manual systems could never support. Yet across every layer, the same structural limitation persists: Systems optimize execution not truth. Baselines remain modeled, additionality remains narrative, verification remains episodic, methodologies remain fragmented, and governance remains procedural. Software simply industrialized these assumptions. The modern carbon technology stack therefore resembles a high-speed financial network built atop pre-digital regulatory logic. It moves assets faster, processes data cheaper, and scales participation globally but it was never architected to continuously validate environmental reality, stress-test economic plausibility, or manage systemic integrity risk. Digitization accelerated execution by embedding baseline assumptions, methodological formulas, and approval logic directly into code — scaling existing integrity weaknesses at software speed rather than redesigning how trust is continuously verified. And this is precisely where the modern credibility crisis was engineered not by lack of technology, but by scaling workflows without rebuilding the infrastructure of verification, governance, and integrity itself.

How Current Software Misses the Mark: first platforms such as Persefoni, Watershed, Sweep, Normative, Plan A, Salesforce Net Zero Cloud, and Microsoft Sustainability Manager treat dashboards, workflows, calculation engines, registries, and reporting automation as sufficient market infrastructure, even though these layers primarily accelerate execution of inherited assumptions rather than continuously validating environmental reality, enabling organizations to process emissions inventories, disclosures, and offset portfolios faster without fundamentally improving the credibility of underlying data; second across both enterprise carbon management systems and project-level MRV platforms, success metrics are overwhelmingly optimized around operational KPIs such as faster documentation cycles, reduced audit costs, higher project throughput, and smoother regulatory submissions — visible in voluntary market pipeline tools such as Patch, Carbonfuture, Sylvera’s project workflows, and registry-integrated MRV platforms — while baseline realism, additionality credibility, permanence risk, and systemic over-crediting patterns remain outside core software logic; third automated calculation engines embedded in platforms executing methodologies for standards such as Verra, Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve, and in nature-based solution SaaS tools applying AI biomass and sequestration models industrialize counterfactual projections at scale without embedding continuous stress-testing, economic plausibility checks, or cross-project anomaly detection capable of surfacing baseline inflation trends before credit issuance; fourth modern registries including Verra Registry, Gold Standard Impact Registry, national ETS registries across the EU and Asia, and newer blockchain-linked infrastructures such as Toucan function as high-speed ownership and settlement systems that efficiently prevent double counting yet integrate almost no scientific verification layers that interrogate whether credits entering the ledger reflect durable, additional, and continuously verified climate outcomes; finally sophisticated disclosure and reporting platforms now enable real-time ESG dashboards, automated regulatory submissions, and portfolio-level emissions analytics across thousands of corporations, but continue to rely predominantly on emissions-factor estimation rather than primary measurement data — particularly across Scope 3 supply chains — creating the appearance of precision, control, and compliance while leaving integrity intelligence largely external, episodic, and assumption-driven.

What We Learned from Real Country Experience: first in the European Union’s Emissions Trading System, the digitization of registries and automated allowance tracking dramatically improved compliance efficiency and market liquidity, yet baseline allocation rules and sector benchmarks required repeated political adjustment as over-allocation emerged in early phases, showing that software scaled transactions faster than governance could correct distortions; second in California’s cap-and-trade system, digital reporting platforms enabled rapid emissions disclosure across thousands of facilities, while verification remained periodic and project-by-project, limiting regulators’ ability to detect systemic over-crediting or evolving economic shifts in real time; third in China’s national carbon market, centralized digital MRV systems allowed millions of tonnes of emissions data to be processed annually, but uneven baseline methodologies across power plants and provinces highlighted how automation expanded coverage without harmonizing integrity; fourth across voluntary market host countries such as Kenya, Peru, and Indonesia, where projects are processed through international registry infrastructures such as Verra’s Registry and Gold Standard’s Impact Registry, digital MRV platforms and registry workflow interfaces have significantly reduced documentation friction and approval timelines for forestry and nature-based projects, while underlying credit volumes continue to depend primarily on modeled baselines and periodic verification cycles rather than continuous performance measurement, yet reliance on modeled sequestration and narrative additionality continued to produce large credit volumes with limited continuous verification of on-the-ground outcomes; finally across jurisdictions such as South Africa and Colombia, where national MRV systems and carbon tax or market-linked registry frameworks are being developed to support NDC reporting and future trading mechanisms, workflow digitization improved administrative capacity while institutional governance frameworks struggled to evolve fast enough to manage integrity risk as participation scaled.

Lessons from Capital Markets: first successful markets never rely solely on transaction platforms and reporting tools but embed verification, surveillance, and risk controls directly into operational infrastructure; second automation increases scale safely only when the rules being automated are continuously monitored and adjusted through systemic oversight mechanisms; third registries and settlement systems function effectively because asset validity is governed by standardized verification frameworks operating beneath the transaction layer; fourth reporting technology enhances transparency but cannot substitute for embedded controls that ensure data reflects real economic and physical outcomes; finally markets achieved durability by designing infrastructure that governs trust first and efficiency second, whereas carbon platforms reversed this sequence by scaling efficiency without constructing equivalent integrity architecture.

The Software Fallacy: Treating Carbon as a Reporting Problem Instead of Market Infrastructure

This illustration portrays the growing tension between high-speed carbon reporting tools and the deeper market infrastructure they were never designed to replace. On the left, emissions data is processed through dashboards and automated workflows that prioritize documentation and throughput. In the center, a decision-maker hesitates, caught between procedural compliance and real credibility. On the right, the complex machinery of markets, institutions, and financial systems continues to operate without integrated integrity controls, highlighting how digitized processes have advanced faster than systems of trust.

As carbon markets scaled rapidly under regulatory pressure and corporate net-zero commitments, the dominant framing across both policy institutions and technology providers became that the core challenge of climate action was insufficient data visibility and inefficient reporting. From the policy infrastructure perspective, regulators sought standardized emissions inventories, harmonized disclosures, and digital submission pipelines to monitor compliance across thousands of firms. From the market perspective, corporations and project developers wanted faster footprint calculation, streamlined documentation, and easier audit readiness to reduce administrative burden and accelerate participation.

Rather than redesigning the economic and governance architecture of carbon markets, software platforms overwhelmingly focused on digitizing how emissions data is collected, organized, and disclosed. This resulted in a reporting-centric infrastructure built around: (i) Emissions factor libraries and automated footprint estimation; (ii) Narrative-driven additionality and project justification modules; and (iii) AI-based proxy modeling replacing direct measurement wherever data gaps existed. Each of these elements now dominates modern carbon software.

(i) Emissions Factor Libraries: Scaling Estimates in Place of Measurement: Platforms such as Persefoni, Watershed, Normative, Plan A, Sweep, Salesforce Net Zero Cloud, and Microsoft Sustainability Manager rely heavily on large emissions factor databases to translate financial spend, activity data, and procurement categories into CO₂e values. In practice, multinational firms integrate these tools into ERP systems where supplier invoices, logistics records, and utility bills are automatically converted into emissions estimates using sector-average coefficients. Under policy frameworks such as the GHG Protocol and CSRD, this approach enables standardized Scope 3 reporting across complex global value chains. From a market perspective, emissions factor automation allows corporations to produce comprehensive carbon inventories rapidly without requiring direct measurement from thousands of suppliers. However, in most enterprise deployments, between 70 percent and 95 percent of Scope 3 emissions remain modeled rather than measured, meaning that reported carbon footprints are statistical abstractions built on average assumptions rather than physical reality. While this dramatically improves disclosure coverage, it does not verify real-world emissions outcomes. High-volume reporting is achieved, but integrity remains probabilistic.

Coverage expanded. Measurement certainty did not.

(ii) Narrative Additionality Logic: Digitizing Subjectivity: Project-level platforms embedded across voluntary markets now include structured justification modules where developers explain why projects would not occur without carbon revenue. These appear within registry workflows, MRV SaaS tools, and project management systems used by standards such as Verra, Gold Standard, and emerging removal registries, as well as private project pipeline platforms like Patch, Carbonfuture, and various nature-based solution software suites. Developers upload financial projections, risk narratives, and market barrier explanations through guided digital forms that mirror historical additionality documentation. From the policy infrastructure side, this creates standardized submission logic that can be reviewed efficiently by validators. From the market side, it reduces documentation friction and accelerates credit approval timelines. Yet the underlying logic remains narrative rather than empirically verifiable. Financial viability assumptions are rarely stress-tested against independent market data, alternative financing sources, or systemic economic trends. Once digitized, these subjective claims move faster through approval pipelines without becoming more truthful.

Process speed improved. Economic realism did not.

(iii) AI Proxy Modeling: Estimating Reality at Scale: An increasing share of modern MRV platforms now rely on machine-learning models to infer emissions outcomes from indirect data sources. Forestry platforms simulate biomass growth and avoided deforestation using satellite imagery and historical land-use patterns. Soil carbon tools estimate sequestration based on farming practices and climate models. Industrial systems infer emissions using energy consumption proxies rather than direct sensor readings. Providers across the carbon tech ecosystem now advertise AI-driven MRV capable of producing credit volumes at scale, often reducing monitoring costs by over 70 percent compared to physical sampling. From a policy perspective, this allows oversight bodies to expand coverage across millions of hectares and thousands of facilities. From a market perspective, it unlocks project economics previously constrained by high measurement costs. Yet these models remain probabilistic estimators layered atop baseline assumptions. They do not replace counterfactual logic. They encode historical patterns into future projections. They often operate as proprietary black boxes where assumptions are difficult for auditors to interrogate. Accuracy improves relative to sparse sampling, but verifiability remains indirect.

Estimation scaled. Verification remained inferential.

Structural Synthesis—Reporting Efficiency Replaced Market Integrity Design: Across emissions factor automation, narrative additionality workflows, and AI proxy modeling, carbon software overwhelmingly treats climate action as a data management challenge rather than a market infrastructure challenge. From the policy side, reporting became standardized, faster, and administratively scalable.

From the market side, participation costs dropped and coverage expanded dramatically. But in every case, reporting automation scaled modeled emissions, narrative additionality, and proxy-based MRV at unprecedented volume, transforming climate accounting into a high-speed estimation system rather than a continuously verifiable measurement infrastructure. The systems optimized how quickly assumptions could be processed, not whether those assumptions reflected real climate outcomes. Carbon accounting became more comprehensive while remaining fundamentally modeled. Software transformed paperwork into dashboards, but it did not transform counterfactual economics into verifiable reality.

How Current Software Misses the Mark: first enterprise platforms such as Persefoni, Watershed, Normative, Sweep, Plan A, Salesforce Net Zero Cloud, and Microsoft Sustainability Manager convert procurement spend, logistics flows, and operational metrics into emissions inventories using sector-average coefficients, enabling rapid Scope 1–3 reporting while leaving the majority of emissions mathematically inferred rather than physically measured; second project-level systems embedded across voluntary markets — including registry workflow tools and pipeline platforms such as Patch, Carbonfuture, and registry-integrated MRV SaaS environments — digitize additionality justifications through structured narrative forms that accelerate approvals without independently validating economic necessity or counterfactual realism; third AI-driven MRV providers across forestry, soil carbon, and industrial mitigation now estimate sequestration and avoidance outcomes using remote sensing and statistical models that dramatically lower monitoring costs but remain probabilistic projections layered atop baseline assumptions rather than continuously verified physical outcomes; fourth reporting platforms increasingly connect directly into regulatory frameworks such as the EU’s CSRD and emerging SEC disclosure rules, optimizing for audit readiness and compliance completeness while leaving integrity intelligence external to the software itself; finally the entire reporting stack measures success in terms of data coverage, processing speed, and disclosure accuracy rather than durability of climate impact or systemic risk reduction.

What We Learned from Real Country Experience: first jurisdictions rolling out digital emissions registries and national reporting platforms, including systems implemented across the European Union’s ETS infrastructure, emerging national MRV frameworks in Latin America, and compliance reporting portals in parts of Asia, achieved dramatic improvements in transparency, reporting frequency, and administrative throughput while continuing to face persistent baseline disputes and integrity challenges tied to methodological assumptions; second government agencies adopting standardized emissions inventories found that coverage expanded rapidly across regulated entities, yet the underlying emissions figures remained heavily model-driven, particularly in complex industrial sectors and value-chain reporting; third national forestry MRV programs integrated with satellite monitoring, including REDD+ frameworks operating across countries such as Indonesia, Peru, and Ghana, significantly improved detection of deforestation and land-use change while credit issuance continued to depend on modeled counterfactuals reviewed through periodic verification cycles, leaving over-crediting risks structurally unresolved; fourth compliance authorities increasingly report that while digital platforms improved audit efficiency, they did not reduce the need for intensive human judgment in assessing plausibility and economic realism; finally credibility concerns persisted not due to lack of data systems, but because institutional mechanisms for continuous integrity governance were never embedded into digital architecture.

Lessons from Capital Markets: first modern financial systems did not stabilize merely by improving reporting frequency or transparency dashboards, but by embedding clearing systems, capital requirements, automated risk controls, and systemic oversight directly into market infrastructure; second accounting visibility alone proved insufficient to prevent crises until governance logic was programmable and continuously enforced; third transaction reporting improved market monitoring, yet real stability emerged only once systemic risk analytics operated across institutions rather than entity by entity; fourth financial regulators shifted from episodic audits to continuous market surveillance to manage complexity at scale; finally credibility in capital markets is now maintained not by disclosure alone but by integrity architecture embedded directly into how markets operate.

Why Verification Remains Procedural Instead of Systemic: Audits at Scale Without Continuous Integrity

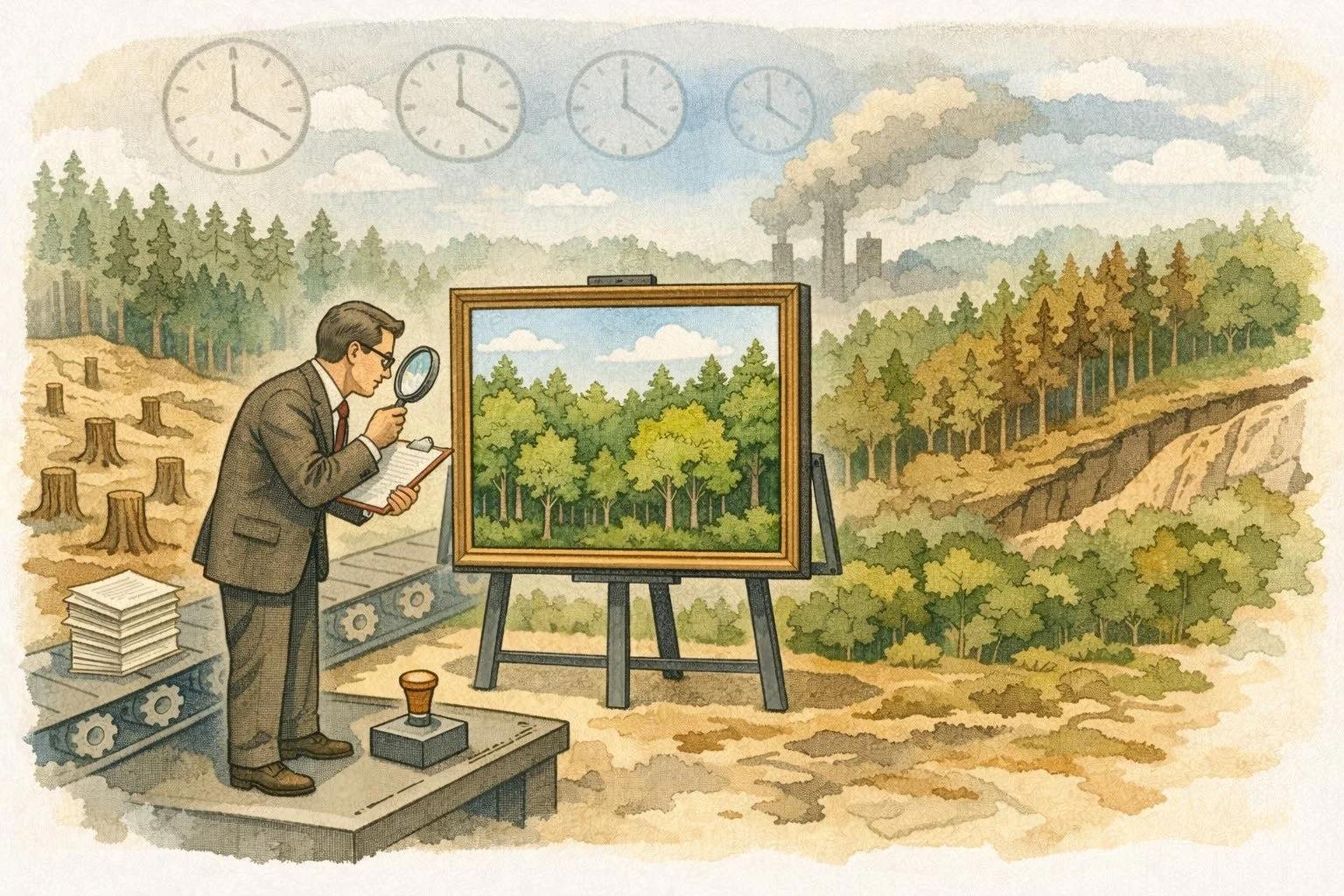

This illustration shows an auditor carefully inspecting a single, pristine snapshot of forest health while the broader landscape quietly degrades around it, symbolizing how carbon verification systems rely on periodic, narrow reviews rather than continuous, system-wide oversight. The framed scene represents compliant documentation and approved evidence, while the surrounding deforestation, smoke, and erosion reveal risks that remain invisible between audits, highlighting how procedural verification can miss slow-moving but structural integrity failures as markets scale.

As carbon markets expanded in both regulatory compliance systems and voluntary project pipelines, verification mechanisms were expected to evolve alongside rising credit volumes, digital MRV adoption, and financial flows. From the policy infrastructure perspective, standards bodies and regulators required independent third-party validation to maintain legitimacy, legal defensibility, and public trust. From the market perspective, project developers and corporate buyers needed predictable, certifiable processes that enabled credits to be issued and retired with confidence while minimizing delays and transaction costs. In response, verification was not rebuilt as real-time integrity infrastructure. It was digitized as an administrative workflow layered on top of legacy audit logic. This produced a modern verification architecture centered on: (i) consultant-driven episodic audits; (ii) snapshot digital evidence reviews using satellite imagery and documentation uploads; and (iii) standardized third-party certification pipelines aligned to individual standards. Each remains procedural rather than systemic.

From the policy perspective, this preserves legal accountability, independence, and professional standards familiar to regulatory regimes. From the market perspective, it creates predictable approval cycles that allow credit issuance schedules to be modeled financially. However, episodic audits cannot detect dynamic changes in project performance, shifting economic conditions, evolving land-use risks, or systemic over-crediting patterns across portfolios. Integrity becomes a periodic snapshot rather than a continuously monitored reality. Once a project passes verification, credits may be issued in bulk based on past conditions that no longer hold.

Professional oversight scaled. Continuous climate reality did not.

(i) Consultant-Driven Audits: Scaling Human Review Rather Than Continuous Oversight: Across both compliance and voluntary markets, verification remains dominated by accredited auditing firms and designated operational entities that conduct periodic project reviews. Large consultancies, environmental audit firms, and specialized carbon verification bodies review monitoring reports, baseline calculations, additionality claims, and evidence packages submitted digitally through registry workflows. In practice, forestry projects, renewable installations, industrial mitigation facilities, and removal initiatives typically undergo verification every one to three years depending on methodology. From the policy perspective, this preserves legal accountability, independence, and professional standards familiar to regulatory regimes. From the market perspective, it creates predictable approval cycles that allow credit issuance schedules to be modeled financially. However, episodic audits cannot detect dynamic changes in project performance, shifting economic conditions, evolving land-use risks, or systemic over-crediting patterns across portfolios. Integrity becomes a periodic snapshot rather than a continuously monitored reality. Once a project passes verification, credits may be issued in bulk based on past conditions that no longer hold.

Professional oversight scaled. Continuous climate reality did not.

(ii) Digital Evidence Reviews: Modern Tools, Legacy Logic: Modern MRV platforms increasingly incorporate satellite imagery, sensor data, photographic evidence, and automated reports into digital verification packages. Forestry developers upload deforestation alerts, canopy change maps, and fire detection overlays. Industrial projects provide automated energy logs and emissions dashboards. From the policy infrastructure side, this improves traceability, documentation quality, and audit transparency. From the market side, it shortens verification cycles and reduces physical inspection costs dramatically. Yet the review process itself remains episodic and case-by-case. Evidence is checked against methodology criteria rather than evaluated within a continuous systemic risk framework. There are no automated cross-project plausibility checks comparing baselines across regions, no real-time monitoring of market-wide credit inflation trends, and no integrated risk scoring that evolves as new data arrives. Digital tools enhance evidence submission but not integrity intelligence.

Evidence got richer. Systemic oversight remained static.

(iii) Standard-Bound Certification Pipelines: Integrity in Silos: Verification remains tightly coupled to individual standards such as Verra, Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve, national ETS authorities, and emerging carbon removal registries. Each operates its own approval logic, audit rules, buffer pools, risk frameworks, and issuance thresholds. From the policy side, this allows methodological specialization and sector-specific governance. From the market side, it enables rapid experimentation and diverse project typologies. But it also creates isolated integrity systems. Over-crediting patterns within one standard rarely trigger alerts in another. Baseline inflation in forestry may not be comparable to industrial methodologies. Risk is assessed per project, not across markets. No unified verification intelligence layer exists to evaluate climate performance system-wide.

Certification scaled. Market-wide integrity did not.

Structural Synthesis—Verification Became Faster, Not Smarter: Across modern carbon markets, digital MRV tools undeniably transformed the operational mechanics of verification by dramatically improving documentation quality, lowering audit costs, and accelerating credit issuance timelines. From the policy infrastructure perspective, regulators and standards bodies gained administrative scalability that made it possible to oversee exponentially larger project pipelines than legacy paper-based systems ever could. From the market perspective, project developers and corporate buyers benefited from faster approvals, predictable issuance cycles, and reduced transaction friction, allowing capital to move more efficiently across geographies and project types.

Yet despite these efficiency gains, verification logic itself never transitioned from procedural review to systemic integrity architecture. What was modernized was the speed of evidence submission and audit processing — not the underlying governance intelligence required to continuously validate climate outcomes at scale. Audits remain fundamentally episodic rather than continuous, meaning environmental performance is still assessed through periodic snapshots rather than real-time monitoring frameworks. Risk remains structurally siloed within individual projects and standards, with little capacity to detect over-crediting patterns, baseline inflation trends, or methodological distortions across markets as a whole. Oversight continues to operate project by project, even as markets function as interconnected financial ecosystems.

At the same time, no continuous plausibility engines exist to stress-test baseline assumptions as economic conditions shift, no market-wide analytics systematically flag abnormal credit volumes across regions or methodologies, and no real-time integrity layers adapt dynamically as environmental data streams evolve. Digital systems have become exceptionally good at moving documentation, processing calculations, and issuing credits faster than ever before, but they were never architected to function as live verification intelligence platforms capable of managing systemic climate risk.

In effect, verification systems scaled audit throughput and documentation flow while remaining structurally incapable of continuous market-wide risk detection, baseline stress-testing, or real-time integrity oversight. Speed scaled. Throughput expanded. Yet the capacity to ensure durable environmental credibility did not evolve in parallel. The modern carbon ecosystem therefore operates with high operational efficiency layered atop governance mechanisms still designed for small, slow, document-driven programs. The result is a verification regime that processes more projects than ever before while remaining structurally incapable of continuously safeguarding integrity across a rapidly expanding global climate market.

How Current Software Misses the Mark: first most MRV and registry platforms modernized evidence submission through satellite uploads, automated reports, and digital audit trails while preserving periodic human review as the primary integrity control mechanism; second verification workflows remain anchored to fixed monitoring cycles, meaning environmental performance is assessed in snapshots rather than continuously tracked against evolving real-world conditions; third no dominant platforms embed automated plausibility engines capable of flagging baseline inflation, abnormal issuance spikes, or cross-project anomalies before credits are approved; fourth risk remains siloed within individual project assessments rather than analyzed across portfolios, sectors, and geographies in real time; finally verification success is measured by processing efficiency and audit completeness rather than by systemic detection of over-crediting patterns or long-term outcome durability.

What We Learned from Real Country Experience: first compliance authorities operating large emissions trading systems — including those within the European Union, South Korea, and emerging national carbon markets in China — dramatically improved reporting and audit throughput through digital registries while continuing to rely on periodic inspections and document-based reviews for integrity control; second forestry oversight agencies integrating satellite monitoring across national REDD+ programs improved deforestation detection but still issued credits based on baseline scenarios reviewed episodically rather than continuously stress-tested; third regulators found that while digital MRV lowered verification costs and expanded coverage, it also increased project volumes faster than institutional capacity to analyze systemic risk; fourth oversight bodies increasingly depend on post-hoc investigations, academic reviews, and journalistic exposure to uncover integrity failures rather than automated market surveillance; finally credibility issues consistently emerged not from lack of monitoring technology but from absence of continuous governance architecture capable of evolving alongside market complexity.

Lessons from Capital Markets: first modern financial oversight shifted away from episodic audits toward continuous market surveillance precisely because snapshot reviews failed to detect systemic risk buildup; second regulators now deploy automated transaction monitoring, anomaly detection, and real-time risk analytics across entire markets rather than relying solely on firm-by-firm inspections; third stress testing became a permanent infrastructure function rather than a periodic compliance exercise; fourth systemic supervision allows early detection of asset inflation, leverage accumulation, and correlated risk exposures before crises emerge; finally market credibility today is sustained not by faster audits but by embedded integrity intelligence operating continuously across financial systems.

Fragmented Governance Embedded in Software Design: When Code Mirrors Institutional Silos

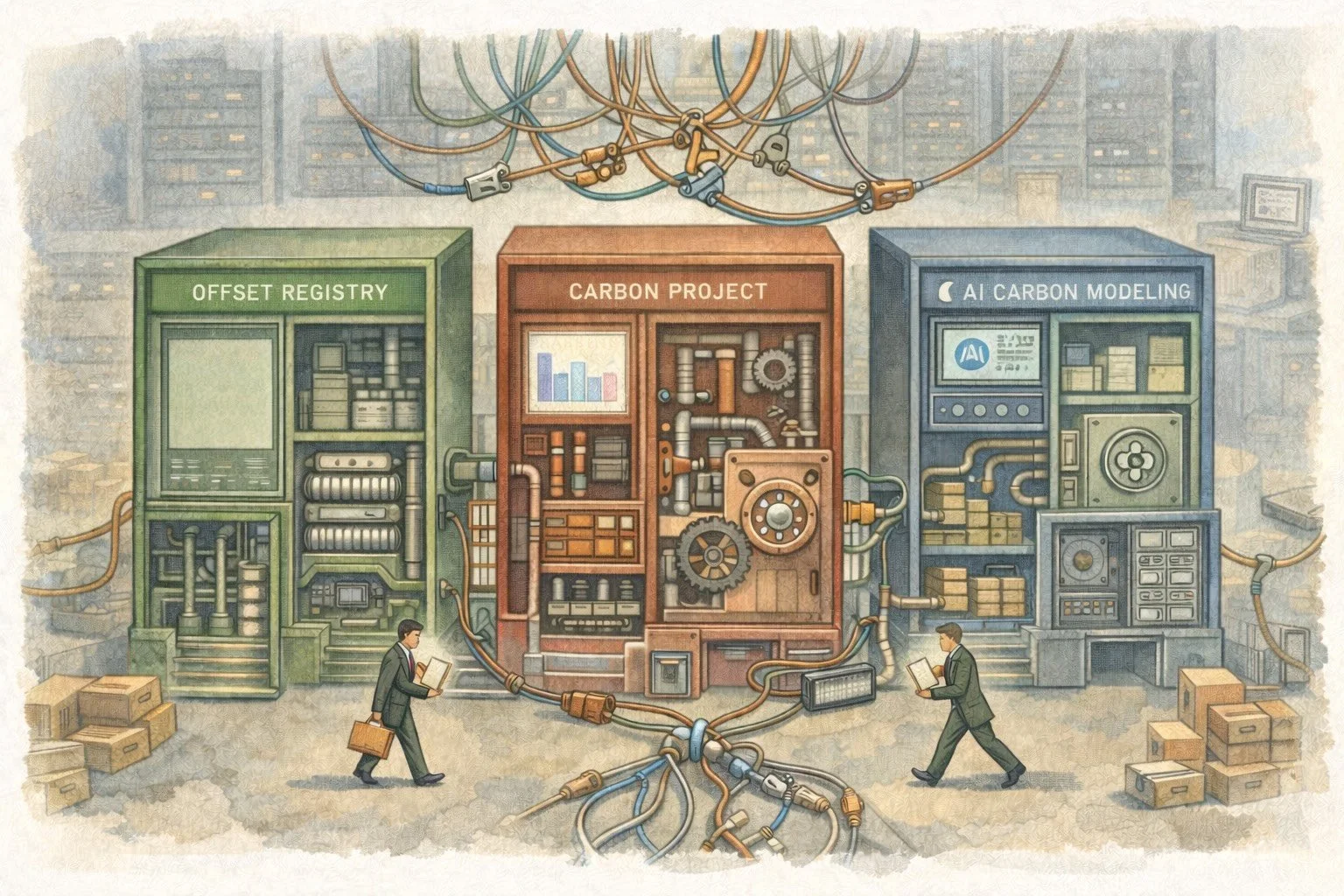

This illustration shows three separate carbon “systems” operating side by side, an offset registry, a project engine, and an AI modeling stack, each internally sophisticated yet structurally disconnected from the others. Tangled cables and improvised adapters suggest attempted integration, but no unified backbone governs them. The scene captures how modern carbon markets digitize components of the workflow while lacking a shared operating system that embeds integrity, interoperability, and systemic oversight across the full market architecture.

As carbon markets expanded across compliance regimes, voluntary standards, corporate net-zero frameworks, and emerging removal registries, governance fragmentation did not simply persist at the institutional level — it became embedded directly into software architecture itself. From the policy infrastructure perspective, each standard evolved independently to address sector-specific needs, political constraints, and methodological philosophies. From the market perspective, this fragmentation allowed rapid innovation, competitive differentiation, and faster adaptation to new project types such as nature-based solutions and engineered removals. However, because software platforms are built to operationalize specific standards and rulebooks, they inevitably encode those fragmented governance logics into digital systems. Rather than converging toward a unified integrity backbone, the carbon technology stack replicated and accelerated institutional silos. This embedded fragmentation manifests across three structural layers: (i) standard-specific logic engines that cannot communicate across systems; (ii) registry-bound data structures that limit interoperability; and (iii) non-harmonized MRV schemas that prevent cross-market comparability.

(i) Standard-Specific Logic Engines: Methodologies as Isolated Code Silos: Most carbon platforms are built to execute the rulebook of a particular standard or regulatory regime. Methodology formulas, buffer pool requirements, permanence risk calculations, and additionality tests are encoded directly into software engines tailored to specific registries or compliance systems. From a policy perspective, this allows standards bodies to preserve methodological sovereignty and adapt rules without external interference. From a market perspective, it enables rapid deployment of projects under diverse crediting approaches and supports innovation across sectors. Yet the result is a proliferation of isolated logic engines. A forestry baseline model under one standard may use fundamentally different assumptions than an adjacent project under another. Removal credits may apply different permanence buffers, leakage rules, or risk discounting methodologies depending on registry affiliation. Because these rules are encoded in separate software stacks, there is no automatic cross-standard stress testing. What appears as diversification from above becomes structural non-comparability beneath the surface.

Governance diversity accelerated. Systemic coherence did not.

(ii) Registry-Bound Data Structures: Ownership Without Interoperability: Digital registries, whether compliance-based or voluntary, operate as discrete ledgers with their own issuance formats, serial numbering conventions, retirement processes, and transaction histories. From the policy perspective, this structure prevents double counting within each registry and preserves regulatory authority over credit flows. From the market perspective, it creates liquidity within defined ecosystems and ensures transactional clarity. However, registry data structures are rarely interoperable at the architectural level. Data formats differ. Risk classifications differ. Project metadata is not standardized across systems. Cross-registry analytics must often rely on manual aggregation or third-party data scraping rather than embedded interoperability protocols. Even when blockchain overlays are introduced, they frequently replicate registry silos rather than unify them. As a result, markets operate as parallel micro-systems rather than as components of a unified climate infrastructure. Credits may be financially fungible within a registry, but environmental comparability across registries remains opaque.

Transaction certainty improved. Cross-market transparency did not.

(iii) Non-Harmonized MRV Schemas: Data Abundance Without Shared Semantics: Modern digital MRV systems ingest massive volumes of satellite imagery, sensor data, project reports, and corporate disclosures. From the policy infrastructure perspective, this dramatically increases observational capacity. From the market perspective, it expands coverage and lowers monitoring costs. Yet MRV schemas differ widely across standards and platforms. Definitions of baseline years, leakage accounting rules, permanence horizons, and risk classifications are not universally harmonized. Even core data categories may be labeled differently across systems, complicating aggregation. AI models trained within one platform may not be transferable to another because underlying data ontologies differ. Without shared semantic frameworks, the carbon ecosystem accumulates data without generating unified intelligence. Policymakers struggle to compare performance across programs. Buyers cannot easily benchmark credit quality across standards. Systemic risk detection becomes nearly impossible when data categories are structurally incompatible.

Data volume exploded. System-wide insight remained constrained.

Structural Synthesis—Fragmentation Scaled Through Code: The fragmentation long recognized at the institutional level has now been deeply encoded into the digital layer of carbon markets. Each standard’s logic is replicated in software. Each registry’s ledger is architected in isolation. Each MRV platform optimizes for its own schema rather than collective comparability. From the policy perspective, this fragmentation enabled flexibility, rapid experimentation, and political feasibility across jurisdictions. From the market perspective, it fostered innovation, competitive differentiation, and accelerated capital mobilization. Yet at the systemic level, digital platforms encoded institutional silos directly into software logic, causing methodological divergence, registry isolation, and data incompatibility to scale alongside market volume rather than converge toward system-wide integrity. Cross-market stress testing remains limited. Baseline plausibility cannot be evaluated consistently across regions. Inflation patterns in one segment do not automatically trigger alerts elsewhere. Governance becomes a patchwork of rulebooks executed at digital speed. The result is a technologically advanced but institutionally segmented ecosystem where efficiency grows horizontally while coherence weakens vertically. Markets scale outward in volume and geography, yet the infrastructure required to evaluate environmental truth across the system as a whole remains absent.

Fragmentation moved from paper into software. Silos became digital. Interoperability remained aspirational rather than architectural.

How Current Software Misses the Mark: first most platforms are architected to execute the rulebook of a single standard or registry, embedding methodological assumptions directly into proprietary code rather than enabling cross-standard comparability; second baseline logic, permanence buffers, and additionality thresholds differ across software systems with no shared integrity layer capable of stress-testing inconsistencies; third registry infrastructure treats credits as valid within isolated ecosystems while lacking embedded mechanisms to compare environmental quality across markets; fourth MRV platforms optimize around their own data ontologies, making cross-platform analytics complex, manual, and often impossible in real time; finally governance fragmentation that was once institutional is now digital, meaning software accelerates silo behavior rather than correcting it.

What We Learned from Real Country Experience: first multi-registry environments across Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia consistently saw overlapping standards operating simultaneously with limited interoperability despite digital modernization; second compliance authorities attempting to align domestic markets with international offset programs struggled to reconcile methodological differences encoded directly into registry software; third governments integrating multiple voluntary standards into national carbon frameworks encountered data incompatibility that prevented unified oversight dashboards; fourth regulatory pilots aiming to harmonize credit quality discovered that fragmented software architectures required costly custom integration layers rather than native interoperability; finally fragmentation persisted not due to political resistance alone, but because digital systems had hard-coded governance separation into their core design.

Lessons from Capital Markets: first modern financial markets allow diverse institutions to coexist precisely because they share common clearing, reporting, and settlement infrastructure; second standardized data schemas enable regulators to monitor systemic risk across banks, exchanges, and asset classes in real time; third interoperability allows asset comparability regardless of which institution issued them; fourth fragmented markets historically produced arbitrage and crises until shared infrastructure was implemented; finally capital markets demonstrate that institutional diversity can thrive only when built atop unified integrity architecture.

The Full-Stack Gap: Dashboards Versus Carbon Operating Systems

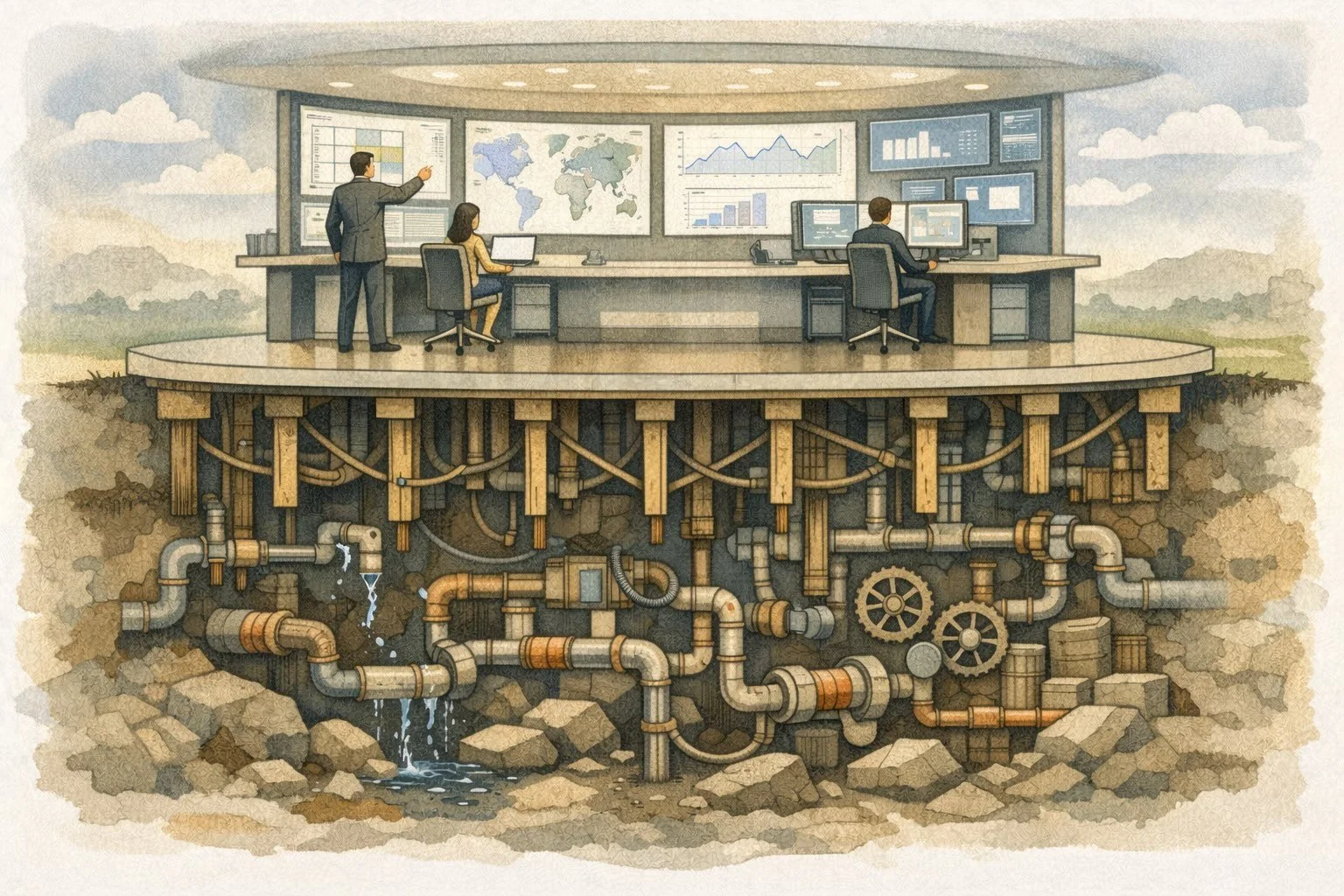

This illustration shows a polished, data-rich dashboard environment where professionals confidently manage carbon metrics above ground, while beneath the surface a tangled, fragile web of pipes, gears, and leaking systems struggles to hold everything together. The calm efficiency of the visible interface contrasts sharply with the unstable infrastructure below, symbolizing how modern carbon platforms prioritize sleek reporting and workflow automation while neglecting the deeper integrity architecture required to govern verification, risk, and trust at market scale.

As carbon markets digitized, most technology platforms naturally evolved around visible operational pain points—reporting complexity, documentation delays, audit bottlenecks, and fragmented data flows. From the market perspective, this made intuitive sense: sustainability teams needed usable interfaces to manage emissions data, project developers needed workflow tools to accelerate credit issuance, and buyers needed dashboards to track portfolios and climate claims. From the policy infrastructure perspective, regulators and standards bodies needed digital submission portals, registry automation, and scalable administrative systems capable of handling surging market volumes. The result was a generation of platforms optimized around front-end usability and workflow efficiency rather than back-end integrity architecture. In effect, the industry built sophisticated visualization and workflow layers while leaving governance intelligence, continuous verification, and systemic risk management outside the core market infrastructure. This distinction is not cosmetic. It is structural: a dashboard organizes information for users, and an operating system governs how a market functions. Modern carbon software overwhelmingly excels at visualization, reporting automation, and process orchestration. What it largely lacks is embedded governance logic capable of continuously verifying environmental reality, stress-testing economic assumptions, and managing systemic integrity risk across the full lifecycle of emissions measurement and credit issuance.

In essence, this pressure did not produce a unified integrity architecture. Instead, it produced a layered software ecosystem optimized around: (i) dashboard-centered design focused on visibility and user interaction; (ii) workflow automation engines built to orchestrate documentation, validation, and issuance processes; and (iii) the absence of a true carbon operating system capable of embedding continuous verification, cross-market intelligence, and systemic risk management into market function itself. Each of these layers improved operational efficiency. None of them fundamentally redesigned trust infrastructure.

(i) Dashboard-Centered Design: Visibility Optimized Without Embedded Validation: Most carbon platforms are architected first and foremost around sophisticated user interfaces that aggregate emissions data, project metrics, satellite imagery, financial flows, and reporting outputs into visually intuitive dashboards. From the market perspective, these interfaces empower sustainability teams, traders, and project developers to monitor performance in real time, identify footprint hotspots, manage credit portfolios, and track progress against net-zero commitments. From the policy infrastructure perspective, dashboards enable standardized data presentation that supports regulatory reviews, disclosure requirements, and oversight processes.

However, dashboards function fundamentally as presentation layers. They display outputs generated by underlying models and workflows — they do not independently verify whether those outputs are environmentally plausible, economically realistic, or methodologically sound. A forest project may show increasing carbon stocks without the system questioning baseline inflation. An industrial offset may display avoided emissions without stress-testing counterfactual assumptions. A corporate footprint dashboard may visualize Scope 3 emissions while relying almost entirely on emissions-factor estimates rather than primary supplier data.

Visibility improved dramatically, yet validation logic remained largely external and procedural. The interface layer became more sophisticated, but the integrity layer beneath it did not evolve into a continuous verification system.

(ii) Workflow Automation Engines: Process Discipline Without Systemic Oversight: Behind dashboards sit workflow engines that orchestrate data submission, documentation review, verification steps, approval sequences, and credit issuance processes. From the market perspective, these engines drastically reduce administrative friction and compress time-to-issuance, allowing developers to scale project pipelines across geographies. From the policy infrastructure perspective, they provide standardized review pathways, digital audit trails, and administrative scalability that manual systems could never support. Yet workflow engines are designed primarily to ensure that required steps occur in the correct order — not that the content flowing through those steps is substantively credible at system scale. A baseline model is uploaded, a verifier reviews it, a registry approves it, and credits are issued. The workflow executes flawlessly. What remains absent is any embedded system that continuously compares baselines across sectors, regions, and historical patterns, stress-tests economic plausibility in real time, or detects systemic over-crediting trends across hundreds of projects simultaneously. Oversight remains bounded to individual project reviews rather than market-wide integrity intelligence.

Process compliance scaled efficiently, while systemic risk management remained largely nonexistent.

(iii) Absence of Carbon Operating Systems: Markets Without Embedded Integrity Infrastructure: What today’s platforms largely lack is the equivalent of a true carbon operating system — infrastructure that embeds trust directly into market function rather than layering verification on top of workflows. From the policy infrastructure perspective, such systems would include programmable governance rules, unified data standards, automated methodological stress-testing, continuous risk monitoring, and interoperable registries operating under shared integrity logic. From the market perspective, they would provide credible asset quality assurance, lower reputational risk, improved capital allocation efficiency, and the ability for markets to scale without recurring credibility collapses.

A genuine carbon operating system would integrate several core components. First, continuous plausibility engines would stress-test baselines against real economic data. Second, cross-market analytics would detect inflation patterns and integrity risks in real time. Third, verifiable data pipelines would link measurement directly to issuance rules. Fourth, interoperable registry infrastructure would be built on shared governance logic. Finally, adaptive methodology governance would be capable of evolving dynamically. In such an architecture, verification would no longer be an episodic human checkpoint, it would become an always-on infrastructure layer.

Trust would be engineered into the market itself rather than audited after the fact.

Structural Synthesis — Productivity Scaled, Integrity Was Never Architected: Across dashboards, workflow engines, and automated reporting layers, modern carbon platforms achieved extraordinary operational efficiency. From the market perspective, transaction costs fell, issuance accelerated, and participation expanded globally. From the policy infrastructure perspective, administrative scalability and regulatory visibility improved dramatically. Yet across every architectural layer, the same structural limitation persists: systems optimize execution rather than truth. Baselines remain modeled, additionality remains narrative, verification remains episodic, and governance remains fragmented. Software industrialized these assumptions rather than redesigning them. The modern carbon technology stack therefore resembles a high-speed financial network built atop pre-digital regulatory logic — capable of moving assets faster and processing data cheaper, but never designed to continuously validate environmental reality or manage systemic integrity risk.

Digitization improved throughput. It did not redesign trust, and it is precisely this architectural gap—not lack of data, not lack of software, and not lack of innovation — that engineered today’s credibility crisis by scaling workflows without rebuilding the infrastructure of verification, governance, and integrity itself.

How Current Software Misses the Mark: first enterprise platforms such as Watershed, Persefoni, Salesforce Net Zero Cloud, Microsoft Sustainability Manager, and Sweep primarily function as visualization and reporting layers that organize emissions data without embedding integrity validation logic; second project platforms like Patch, Carbonfuture, Sylvera, and numerous MRV SaaS tools focus on coordinating documentation and credit flows rather than governing methodological plausibility in real time; third registry systems including Verra, Gold Standard, and national ETS platforms operate as transactional ledgers without integrated scientific performance engines; fourth AI-enabled MRV tools process massive environmental datasets yet feed outputs into the same procedural approval structures rather than into continuous market-wide integrity monitoring; finally no major platform today integrates measurement, issuance, governance, and systemic risk intelligence into a unified operational backbone.

What We Learned from Real Country Experience: first national MRV digitization programs in countries such as Colombia, Indonesia, Kenya, and Ghana successfully deployed emissions dashboards and automated registries that improved transparency and reporting speed while still relying on manual methodology oversight; second compliance markets such as the EU ETS achieved high-speed allowance tracking and reporting but continue to manage baseline and allocation policy through separate regulatory processes outside platform infrastructure; third voluntary market pilots embedded in national climate registries across Africa and Southeast Asia integrated project dashboards without creating cross-program integrity intelligence; fourth governments investing in climate data portals consistently improved administrative efficiency but lacked tools to detect over-crediting or methodological arbitrage across programs; finally software modernization strengthened visibility while leaving systemic trust architecture external to digital systems.

Lessons from Capital Markets: first modern financial systems distinguish clearly between user interfaces and market infrastructure, where dashboards are layered atop clearinghouses, settlement systems, and continuous risk controls; second trading platforms do not themselves define asset integrity — centralized infrastructure enforces solvency, transparency, and systemic stability; third regulators monitor markets through integrated real-time risk engines rather than through periodic document reviews; fourth financial operating systems coordinate data ingestion, transaction settlement, compliance enforcement, and systemic oversight simultaneously; finally without such full-stack infrastructure, financial markets historically suffered repeated credibility collapses similar to what carbon markets now experience.

Institutional Design Matters as Much as Code: Who Owns Integrity in Carbon Markets

This illustration shows two contrasting visions of carbon market governance: on one side, integrity rests on a clearly structured foundation of rules, oversight, and aligned incentives; on the other, fragmented actors operate through disconnected systems built over unstable ground. The chasm between them symbolizes the institutional gap that technology alone cannot bridge. Without clear ownership of baseline realism, methodology evolution, and enforcement authority, even the most advanced software remains layered atop foundations that determine whether markets ultimately earn or erode trust.

As discussions about carbon market reform increasingly focus on technology upgrades, AI-powered MRV, and digital transparency, a deeper structural issue often remains under-examined: software cannot compensate for weak institutional design. From the market perspective, participants seek predictable rules, stable credit quality, enforceable ownership rights, and low reputational risk. From the policy infrastructure perspective, regulators and standards bodies must ensure environmental integrity, political legitimacy, legal defensibility, and cross-border coherence. Yet modern carbon markets were not built around a clearly defined integrity authority or unified governance layer. Instead, oversight responsibilities are distributed across standards bodies, registries, verification firms, project developers, rating agencies, corporate buyers, and occasionally sovereign regulators. This diffusion of authority has now been encoded into digital systems. The integrity challenge therefore reflects not merely technological limitations, but institutional fragmentation across three structural dimensions: (i) baseline ownership and economic counterfactual authority; (ii) methodology governance and rule evolution; and (iii) dispute resolution and accountability mechanisms across fragmented markets.

Each reveals why infrastructure cannot be purely technical.

(i) Baseline Ownership: Who Defines the Counterfactual? At the core of carbon credit valuation lies the baseline — the projection of what emissions would have occurred in the absence of intervention. From the market perspective, baselines directly determine credit volumes and therefore financial returns. From the policy infrastructure perspective, baselines represent the environmental credibility foundation upon which the entire market rests. In most current systems, baselines are defined within methodologies created by standards bodies, then operationalized by project developers and validated by third-party auditors. Software platforms apply these baseline formulas automatically, but they do not independently challenge or stress-test them against broader economic conditions.

No single institutional authority systematically reviews whether baseline assumptions remain realistic as energy markets evolve, commodity prices fluctuate, regulatory environments shift, or deforestation risk declines independently of carbon finance. In some sectors, renewable energy baselines were originally calibrated to markets where projects required carbon revenue to be viable. As technology costs declined, many projects became economically feasible without offsets — yet baseline methodologies did not always adjust dynamically.

When no institution clearly “owns” baseline realism at market scale, software merely executes inherited assumptions. Integrity becomes dependent on static rulebooks rather than adaptive economic governance.

(ii) Methodology Governance: Rulebooks Without Systemic Stress Testing: Methodologies define eligibility criteria, additionality tests, leakage accounting, permanence buffers, and crediting periods. From the policy perspective, methodology governance provides formalized environmental standards and procedural safeguards. From the market perspective, it provides predictability, enabling developers to finance projects under known issuance frameworks. However, methodologies are typically revised through committee processes that can take years. Reforms often occur reactively following investigative scrutiny or academic critique rather than through continuous systemic monitoring. While software platforms automate methodology execution, they rarely incorporate dynamic feedback loops that flag statistical anomalies across projects or sectors. For example, if a specific forestry methodology systematically produces higher credit volumes relative to comparable ecological regions under other standards, no unified integrity engine exists to detect that divergence automatically. Instead, corrections depend on external analysis, journalistic exposure, or voluntary reform initiatives.

Code enforces rulebooks. It does not evaluate whether rulebooks themselves are structurally inflationary. Methodology governance remains institutional and political. Software merely operationalizes decisions already made.

(iii) Dispute Resolution and Accountability: Fragmented Enforcement in a Global Market: When integrity concerns arise — whether related to over-crediting, permanence reversals, additionality failures, or fraudulent reporting — accountability mechanisms vary widely. From the policy infrastructure perspective, some compliance markets possess statutory enforcement authority. From the market perspective, voluntary systems rely heavily on reputational pressure, buffer pools, and standard-led corrective measures. Yet there is no unified global arbitration layer capable of resolving cross-standard disputes, harmonizing credit invalidation rules, or reallocating liability when environmental reversals occur. A wildfire that destroys credited forest carbon may trigger buffer pool adjustments within one registry, but not necessarily across interconnected markets. If credits are later found to be over-issued, retrospective correction mechanisms differ by standard. Software systems reflect these fragmented accountability structures. Registries track issuance and retirement efficiently, but they are not designed to adjudicate systemic liability disputes or cross-market correction cascades. Rating agencies may downgrade project scores, but they lack formal enforcement authority. Corporate buyers may pause purchases, yet they do not govern methodology reform.

Markets operate globally. Accountability remains locally bounded. Without a clearly defined institutional integrity authority embedded into market architecture, governance becomes reactive rather than systemic.

Structural Synthesis—Integrity Is an Institutional Function Before It Is a Technical One: Across baseline ownership, methodology governance, and dispute resolution mechanisms, the same structural reality emerges: carbon market credibility depends as much on who governs integrity as on how software executes calculations. From the market perspective, predictable and credible governance reduces asset risk, lowers reputational exposure, and supports capital mobilization. From the policy infrastructure perspective, institutional coherence ensures environmental legitimacy, public trust, and regulatory durability. Yet current carbon systems distribute integrity responsibilities across fragmented actors without a unified oversight architecture. Software platforms encode these divisions rather than resolve them. Dashboards, workflow engines, and automated registries may operate flawlessly, but they do so within governance frameworks that remain politically negotiated, jurisdictionally fragmented, and episodically reformed.

Integrity cannot be fully digitized if it is not first institutionally centralized or coherently coordinated. Technology can enforce rules. Only institutional design can define credible rules.

Until governance authority, baseline oversight, methodology evolution, and accountability mechanisms are architected as integrated infrastructure rather than dispersed responsibilities, carbon markets will continue to rely on procedural audits layered atop structurally fragile foundations.

How Current Software Misses the Mark: first platforms such as Verra Registry systems, Gold Standard Impact Registry tools, Patch pipelines, and Carbonfuture marketplaces operationalize individual standards without integrating cross-standard integrity intelligence; second corporate accounting platforms like Persefoni and Watershed ingest emissions data but do not govern baseline assumptions embedded within project credit supply; third MRV SaaS providers automate methodological execution without possessing authority to recalibrate rules when economic conditions shift; fourth registries function as ownership ledgers rather than as systemic integrity regulators; finally no software layer currently possesses mandate or architecture to coordinate market-wide oversight across voluntary and compliance regimes.

What We Learned from Real Country Experience: first the European Union centralized emissions compliance authority within the EU ETS while leaving voluntary offset governance outside regulatory scope, producing two parallel integrity regimes operating through separate digital systems; second countries such as Chile, Colombia, and South Africa developed national carbon registries connected to Paris Agreement Article 6 mechanisms, yet baseline methodologies and verification rules remain largely inherited from international standards bodies; third Indonesia’s jurisdictional forestry credit frameworks integrate national oversight but still rely heavily on Verra-style methodologies executed through external platforms; fourth Kenya and Ghana piloted digital MRV and registry infrastructure while governance of additionality and crediting thresholds remained fragmented across ministries and private verifiers; finally governments consistently improved transaction transparency while lacking centralized authority to recalibrate integrity rules dynamically as markets evolved.

Lessons from Capital Markets: first modern financial systems consolidated integrity authority through central banks, securities regulators, clearinghouses, and systemic risk monitors rather than dispersing it across individual trading platforms; second asset valuation rules, disclosure standards, and risk controls are governed institutionally rather than left to market participants; third market infrastructure entities possess explicit mandates to halt trading, adjust requirements, and enforce corrective actions when systemic risk emerges; fourth technology executes these rules but does not define them; finally financial market credibility depends on centralized institutional ownership of integrity layered into digital infrastructure itself.

What True Carbon Infrastructure Requires: From Workflow Digitization to Programmable Integrity Architecture

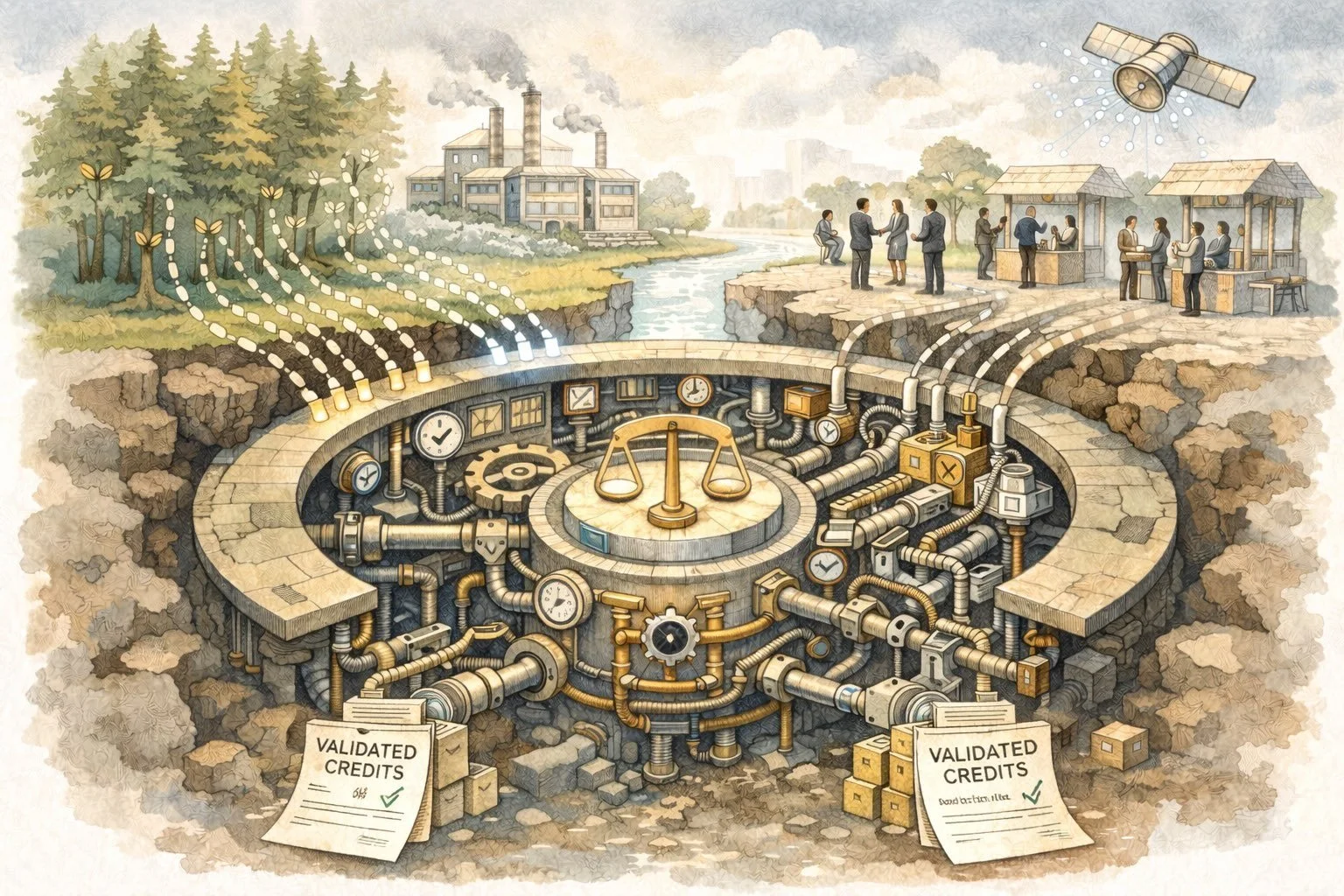

This illustration shows what seems like an integrity engine beneath the surface of carbon markets, where real-world environmental data flows through multiple verification channels before converging inside a central governance machine that transforms raw inputs into validated credits, emphasizing that trust is not created by reporting alone but engineered through continuous oversight, interconnected systems, and institutional checks that operate quietly yet decisively below the visible marketplace.