Tracing French Urban DNA:

Exploring Planning Legacies in U.S. Cities

OHK Study Reveals How French Planning Shaped the Spatial Logic of Major U.S. Cities—Analyzing Historical Foundations Through the Lens of Urban Form and Civic Design

At OHK, our commitment to urban regeneration and historical preservation has taken us across continents, from the intricate street grids of 19th-century Cairo to the dense courtyards of colonial North African towns. A defining thread in many of these projects has been the enduring influence of French urban planning principles—manifested in axial alignments, monumental civic spaces, and elegant public squares. Our recent leadership role in the revitalization of Downtown Cairo, a district deeply shaped by French planning ideals during the time of Khedive Ismail, served as both a proving ground and a springboard. It pushed us to ask: where else have these same planning logics shaped cities in ways we no longer fully see or name? This inquiry led our U.S.-based team to organize a research workshop exploring the French planning legacy in American cities—an influence often overshadowed by Anglo-American colonial narratives or later industrial grids. We found that the French imprint, while subtler in some cases, is undeniable and foundational in others. From the radial geometry of Washington, D.C., inspired directly by French engineer Pierre L’Enfant and his Baroque ideals, to the courtyard urbanism and arcaded streets of New Orleans, shaped by French and Caribbean crosscurrents, American cities reflect more French DNA than many realize.

This investigation charts that legacy across four urban centers: Washington, D.C., New Orleans, St. Louis, and Detroit. Each city offers a unique case: Washington reflects ceremonial urbanism, symmetry, and power through monumental space; New Orleans, the most visibly “French” city in America, retains colonial layouts, compact density, and climate-responsive design; St. Louis preserves traces of early French spatial logic in the area around Laclede’s Landing; and Detroit, shaped by French ribbon farms and a Baroque-inspired radial plan, shows the deep structural mark of French surveying and Enlightenment rationality. In what follows, we unpack the specific planning features of each city and pair them with their closest French or French-colonial precedents. This isn’t just an exercise in historical curiosity—it’s part of OHK’s ongoing mission to understand how past spatial ideologies can guide future regeneration. Recognizing these embedded design patterns helps cities reclaim and reinterpret their identities—not as generic urban centers, but as layered, historically shaped places of meaning.

Reading Time: 35 min.

Unlike other cities shaped by French planning—where French influence was layered atop existing urban fabrics or colonial settlements—Washington, D.C. stands apart as the rare case of a capital city designed from scratch, with French Baroque principles embedded at its very core rather than merely adapted.

📍 L’Enfant’s Republic: How French Planning Principles Shaped the Foundation of Washington, D.C.—The aerial view of the National Mall in Washington, D.C.—a grand axial space envisioned by Pierre Charles L’Enfant in 1791. This monumental vista, stretching from the Capitol to the Lincoln Memorial, reflects the deep imprint of French Baroque planning ideals: symmetry, hierarchy, and visual drama. The orderly rhythm of tree-lined paths and open lawns echoes the spatial language of Versailles and Paris.

Though adapted for a democratic republic, the design’s ceremonial logic (as shown in the photo) mirrors the very European traditions that inspired it—underscoring how D.C.’s identity as a capital is rooted in a uniquely French vision of civic space and urban power. When we trace the spatial logic of Washington, D.C., we find that the imprint of French planning is not just symbolic—it is foundational. This legacy begins with the appointment of Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a French-born engineer and former officer under George Washington during the Revolutionary War, who in 1791 was tasked with designing the new capital city of the United States. Drawing on the grandeur of Baroque French planning, L’Enfant envisioned a city that would physically express the ideals of the republic: open, ordered, and monumental. Rather than replicate the rigid colonial grids found in Philadelphia or Boston, L’Enfant proposed a layered scheme—a rational grid overlaid with ceremonial diagonals, punctuated by grand vistas, circles, and civic axes. It was a revolutionary plan that drew deeply from the French urban tradition, particularly the planning of Versailles, Paris, and other European capitals where geometry and power were tightly intertwined.

Though his relationship with Congress broke down and his plan was only partially implemented at first, L’Enfant’s vision endured. Over the 19th and early 20th centuries, planners and architects—particularly those influenced by the École des Beaux-Arts—returned to his original drawings, restoring and expanding them through efforts like the McMillan Plan of 1901. This re-centering of L’Enfant’s Baroque vision solidified Washington’s identity as a city of ceremonial grandeur, axial composition, and monumental space. In this section, we explore how these French planning ideas shaped five defining features of Washington’s design. Each is paired with its closest French or European counterpart to show how spatial ideologies crossed the Atlantic—and how they helped turn Washington, D.C. into a uniquely American capital with unmistakably French bones.

While cities like Algiers, Hanoi, or New Orleans incorporated French elements into preexisting grids or topographies, Washington D.C. was conceived as a tabula rasa—an opportunity to translate Old World grandeur into New World ideals. This made it not just a city with French influence, but a city born of French spatial thinking, repurposed to express republicanism rather than monarchy. The result is a uniquely American civic landscape, one that embodies Enlightenment geometry but eschews the palace—centering instead on the Capitol and the people’s institutions.

📍 Grand Radial Avenues that Intersect a Grid: Washington, D.C.’s Diagonal Plan and Paris’ Place de l’Étoile—The picture above shows Pennsylvania Avenue, which serves as one of Washington, D.C.’s principal diagonal avenues—linking the White House to the Capitol and embodying the ceremonial and symbolic intent of L’Enfant’s French-inspired urban plan. One of the most direct and compelling precedents for Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s plan for Washington, D.C. is the Place de l’Étoile in Paris, where twelve grand avenues radiate outward from the Arc de Triomphe, forming a dramatic star-like pattern at the city's western edge. This hub of radiating boulevards, first laid out in the mid-19th century and later formalized under Baron Haussmann, was not just a transportation strategy—it was a deliberate expression of ceremonial geometry. The form symbolizes centralized power, spatial clarity, and the orchestration of urban movement toward monumental space. L’Enfant, trained in European design traditions and influenced by the French Baroque, applied similar logic to the American capital a full half-century earlier. His 1791 plan for Washington superimposed a radial system over a rectilinear grid—diagonal avenues like Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and Connecticut Avenues cut across the Cartesian logic of the grid, linking important civic destinations and generating symbolic vistas. These diagonals culminate in circles, squares, and civic monuments, producing a sense of movement and hierarchy in space.

While the medieval street layout of Paris necessitated Haussmann’s later interventions, Washington was a blank slate. Yet the underlying principle was the same: merge geometry with symbolism. The combination of radial and orthogonal elements in both cities generates what urban theorists call layered legibility—a hierarchy of movement and attention that guides people both intuitively and ceremonially. In both Paris and Washington, the radial-grid hybrid serves to anchor the city around nodes of civic power. In Place de l’Étoile, it is the Arc de Triomphe; in D.C., it is the Capitol, the White House, and major circles like Dupont and Logan. These spatial convergences elevate otherwise functional intersections into places of identity, orientation, and symbolic gravitas.

📍 Axis of Ideals: Monumentality and Sightlines from Paris to Washington, D.C.—The Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris viewed from the Arc de Triomphe is a grand axial boulevard exemplifies the ceremonial power of French urban planning. As the spine of the Axe Historique—a ceremonial east–west axis that begins at the Louvre, runs through the Place de la Concorde, continues past the Arc de Triomphe, and stretches into La Défense, it links the city’s monumental past to its civic present, offering a clear visual and symbolic alignment that inspired the design of Washington, D.C.’s National Mall—where similar sightlines structure civic space around democratic ideals. Monumental axes are among the most powerful tools in the urban design tradition, and no two cities better exemplify this strategy than Paris and Washington, D.C. In both capitals, urban grandeur is staged through deliberate linearity: long, open sightlines that culminate in symbols of political, cultural, or historical authority. This choreography of space does more than organize movement—it narrates power. This alignment links monarchic history, revolutionary memory, and modern finance, creating a continuous narrative of French statehood through urban space.

Similarly, Washington, D.C.'s National Mall functions as its own axis of ideals. Designed initially by Pierre L’Enfant and later reimagined through the McMillan Plan of 1901—a comprehensive urban redesign proposal for Washington, D.C., created by the Senate Park Commission to restore and expand Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s original 1791 vision for the capital, the Mall connects the Capitol on the east with the Lincoln Memorial on the west, and aligns the Washington Monument and White House on a secondary axis. This spatial layout was heavily influenced by French Baroque planning, particularly Versailles and Paris, but it was adapted to convey republican symbolism rather than imperial spectacle. What sets Washington apart is its democratic reinterpretation of the monumental axis. Where Paris centers on monuments to royal and national power, D.C.'s axis anchors itself in institutions of governance and civic memory. The Capitol is not a palace; it’s a forum. The Mall is not a royal garden; it’s a public common. In both cities, however, the logic remains: the axis frames the state as visible, ordered, and symbolically elevated. Sightlines discipline the landscape, and in doing so, guide the citizen’s eye—and imagination—toward national ideals. This French legacy, refashioned in the American context, underscores how urban design can shape not only the movement of people, but the meaning of place.

📍 Avenue as Aesthetic and Order: Haussmann’s Paris and the Boulevards of Washington, D.C.—Boulevard Haussmann in Paris, a hallmark of Haussmann’s 19th-century transformation of the city, combines tree-lined elegance with rational planning. This model directly influenced the broad, axial boulevards of Washington, D.C., where similar design logic was adapted to express democratic ideals and civic openness. One of the most enduring elements of French planning influence on Washington, D.C. is the presence of broad, tree-lined boulevards—a feature directly inspired by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s transformation of Paris in the mid-19th century. Under Emperor Napoleon III, Haussmann redesigned the French capital by carving sweeping boulevards through its dense, medieval fabric. These boulevards—such as Boulevard Haussmann, Boulevard Saint-Michel, and Avenue de l’Opéra—were not just about beauty; they were tools of modernization, combining aesthetic grandeur, public health, and social control. Haussmann’s boulevards were wide, symmetrical, and flanked by rows of trees, allowing for fresh air, sunlight, and efficient movement. Their openness created visual rhythm and long vistas, while their scale accommodated carriages, pedestrians, and—crucially—military troops. The design also allowed for uniform building facades, turning streets into galleries of urban order.

In Washington, D.C., this concept was reinterpreted with American democratic values in mind. Avenues like Massachusetts Avenue, Connecticut Avenue, and Pennsylvania Avenue were laid out to echo Haussmann’s logic—long, axial corridors lined with trees and intersecting circles. Though D.C. did not have the medieval density Paris once did, the boulevards still served to promote public hygiene, frame civic buildings, and symbolize national openness. Tree-lined streets in D.C. became both functional and ceremonial. They softened the scale of monumental architecture, provided shade and comfort in the capital’s humid climate, and symbolized rational governance in spatial form. Unlike Haussmann’s boulevards, which often displaced communities and imposed top-down authority, Washington’s avenues were designed into the city from the start—woven into L’Enfant’s plan and later reinforced by the McMillan Commission. The result is a capital where movement feels stately rather than rushed, and where the urban landscape supports both civic pride and democratic accessibility. The boulevard, in both cities, is more than a street: it is a visual and spatial ideology, making political order legible to the public through trees, width, and rhythm.

📍 Civic Centers of Geometry: French Plazas and Washington’s Democratic Circles—Place des Vosges in Paris, a model of geometric symmetry and civic grace, inspired the spatial logic behind Washington, D.C.’s iconic traffic circles. Both serve as anchors of urban order and public life. While Place des Vosges in Paris and Washington, D.C.’s traffic circles differ in form—square vs. circular—they are linked by a shared planning philosophy rooted in French spatial order, symmetry, and ceremonial punctuation. The inspiration lies less in geometry and more in urban function and symbolism. Place des Vosges, built in the early 17th century under Henri IV, was one of the first planned public squares in Europe, organized with a central void framed by regular, harmonious facades. It served as both an architectural showpiece and a civic space—a place where movement slowed, gatherings occurred, and power was quietly framed in symmetry. In Washington, D.C., Pierre L’Enfant adopted this logic of geometric punctuation in his 1791 plan—not as squares, but as circles placed strategically at the intersections of major diagonal avenues and the city’s orthogonal grid. Circles like Dupont, Logan, and Scott create formal pauses in the city’s movement, acting as urban anchors, much like Place des Vosges. Place des Vosges inspired Washington not by direct imitation, but through a planning philosophy: that cities should be structured around geometrically defined public spaces that blend beauty, symbolism, and social purpose. In that sense, Washington’s traffic circles are a democratic reinterpretation of Paris’s aristocratic square—open, accessible, and woven into the life of the republic.

The integration of public squares and civic gathering spaces is a hallmark of French urbanism, and its reinterpretation in Washington, D.C. illustrates how form and meaning travel across continents and political ideologies. While many European cities rely on rectilinear plazas or piazzas, D.C. stands apart in its use of circles—notably Dupont Circle, Logan Circle, Scott Circle, and others. These circular spaces serve as traffic organizers, civic landmarks, and social commons, echoing the spatial principles of French plazas while reimagining them in the language of the American capital. A strong French precedent lies in the Place des Vosges in Paris, as noted; this plaza was not simply decorative—it was a civic space designed for public interaction, commerce, and courtly leisure. Similarly, Place Bellecour in Lyon—one of the largest open squares in Europe—balances openness with surrounding architectural rhythm, anchoring the city’s spatial order while remaining entirely walkable and civic in scale. Washington, D.C.’s circles depart from the square tradition but embody the same logic of centering and spatial punctuation. Dupont Circle, for instance, operates as a convergence point for radial avenues while maintaining a landscaped core, surrounding benches, public art, and layered pedestrian access. These circles calm traffic, orient the street grid, and elevate public space into something legible, legible, and symbolic. The inclusion of monuments and statuary, much like in French plazas, enhances their role as spaces of collective memory. What distinguishes D.C. is how these French spatial ideals are made democratic. Where French plazas were once elite domains—designed for royal processions or aristocratic promenades—Washington’s circles are open, egalitarian, and civic in function. They embody L’Enfant’s vision of a city where space reflects accessible governance and geometric beauty, rather than inherited privilege. In both cities, these public spaces are not just voids, but designed pauses—places where the city breathes, reflects, and gathers.

📍 Dupont Circle from Above: A Democratic Geometry Inspired by French Civic Space—This aerial image of Dupont Circle in Washington, D.C. captures more than just a traffic junction—it reveals a deeply intentional piece of urban choreography, designed to structure movement, frame public life, and elevate civic experience. From this perspective, we see the intersection of diagonals and grid lines, with avenues like Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire radiating from the circle like spokes from a hub. At the center: a tranquil, tree-shaded plaza with a fountain ringed by pathways, seating, and greenery—clearly inviting not just motion, but pause. Dupont Circle, like other traffic circles in D.C., reflects L’Enfant’s vision for a city composed of layered geometries, intentionally broke from the rigid colonial grid to integrate radial avenues and punctuating nodes—a language inherited from cities like Versailles and Paris. In contrast to many traffic rotaries in American cities, Dupont Circle is not merely infrastructural. It is a civic space embedded within the transportation network, a democratic island of calm amid urban velocity. Its tree-lined green core softens the built environment, offers shade and reflection, and hosts impromptu gatherings, protests, musical performances, and conversations. It is a space that belongs to the people—not fenced off, not privatized, but integrated into everyday life.

Instead of monumentalizing monarchy, spaces like Dupont Circle center human scale, visibility, and access. The geometry may recall absolutist traditions, but its use—open, layered, collective—is entirely republican. Seen from above, Dupont Circle is more than a round park; it is a confluence of planning ideals: beauty and utility, movement and rest, hierarchy and openness. It exemplifies how urban form can reflect political philosophy, turning even a traffic circle into a gesture of public dignity. In his letter to George Washington accompanying the plan, L’Enfant wrote that his design aimed to “combine the convenience of regularity with the agreeable diversity of varied views.” He spoke of placing public buildings on prominent sites, connected by broad avenues that would "open to public edifices" and “invite the eye.” That’s not just traffic planning—that’s spatial storytelling. While the geometry recalls absolutist planning, L’Enfant recast it for the American context. For example: Capitol Hill replaces the palace as the visual anchor, circles like Dupont and Logan are not parade grounds but livable green spaces, and the axes do not radiate from a king’s bedroom, but from public institutions of governance. Therefore, it is reasonable to say, L’Enfant deliberately took the symbolic tools of royal urbanism and retooled them to serve a new political vision. In doing so, he helped invent a uniquely American ceremonial urbanism—one where power is visible but not imposing, elevated but not exclusive, and shared across a city designed for civic engagement.

📍 From Absolutism to Republic: Ceremonial Space from Versailles to Washington, D.C.—This diptych presents two masterplans of ceremonial urbanism: the 1746 plan of Versailles by Abbé Delagrive (left) and the 1901 McMillan Plan for Washington, D.C. (right). Abbé Delagrive’s engraving, titled “Plan of Versailles, of the small park, and its outbuildings…” (Bibliothèque nationale de France), documents the gardens, palace, and urban dependencies with extraordinary precision—emphasizing the absolute centrality of the king’s domain, where all geometry radiates from royal authority. On the right, the McMillan Plan translates this spatial logic to a democratic context. Building upon Pierre L’Enfant’s original 1791 layout, the plan reinstates grand axes, radial boulevards, and a monumental core centered on civic buildings—the Capitol, the Mall, and the Lincoln Memorial. Together, these two plans illustrate how geometry, order, and visibility have long been tools of statecraft—first to glorify monarchy, then to embody republican ideals.

Of all the legacies of French planning visible in Washington, D.C., none is more profound—or more politically symbolic—than its commitment to ceremonial urbanism. This is the practice of designing cities not merely for function, but to stage power, structure hierarchy, and express governance through space. The clearest French precedent for this is the Palace of Versailles, where the landscape and city plan were deliberately crafted to reflect and amplify absolute monarchical authority. At Versailles, all roads, gardens, and sightlines radiate from the central axis of the Château, reinforcing King Louis XIV as the focal point of the nation. This is power materialized in geometry: axial avenues, monumental entrances, and controlled vistas all served to script social order and elevate royal prestige. The physical layout imposed a visual and behavioral discipline that reflected—and reinforced—France’s centralized state. In Washington, D.C., Pierre L’Enfant absorbed these lessons but reinterpreted them through the lens of republican ideals. His plan placed Capitol Hill at the symbolic center of gravity—elevated both literally and ideologically. From it radiate the principal avenues of the city, including Pennsylvania Avenue, which connects the Capitol with the White House. This structure evokes Versailles, but replaces the palace with the seat of representative government, making power accessible, visible, and civic. Yet the theatricality of space—the grand processional avenues, the dramatic vistas, the placement of monuments along axial alignments—remains deeply French in its origins. The idea is not just to move through the city, but to experience a sequence of symbolic spaces that guide the citizen’s understanding of authority, memory, and national purpose. Whereas Versailles projected the glory of one ruler, D.C. monumentalizes the institutions of democracy. The spatial hierarchy remains, but its meaning has shifted—from divine kingship to civic participation. What unites both cities is a belief that urban form can teach political values, and that power, to be legible, must be inscribed on the landscape.

While L’Enfant did not design Versailles, he was deeply influenced by the French Baroque planning traditions it embodied—traditions he would have absorbed through his training as a military engineer and his exposure to France’s classical urbanism. The 1746 engraving by Abbé Delagrive, featured on the left, predates L’Enfant’s birth but captures the spatial logic that shaped his thinking: axiality, radial geometry, and hierarchical organization centered on symbolic structures. On the right, the McMillan Plan of 1901, developed more than a century after L’Enfant’s original 1791 plan for Washington, D.C., was not a replacement but a restoration and amplification of L’Enfant’s vision. Where L’Enfant proposed a city of symbolic diagonals and civic nodes, the McMillan Commission refined this into a more unified and formally monumental core—especially in the design of the National Mall. Thus, although L’Enfant is the key figure in shaping D.C.’s ceremonial logic, the diptych pairs Delagrive’s engraving as a source of influence, and the McMillan Plan as its enduring legacy.

New Orleans’ French Quarter stands as the most enduring French urban imprint in the United States. Unlike cities where French influence was overlaid, New Orleans synthesized French planning, Caribbean climate responses, and local cultural adaptation into a living urban model of density, civic space, and architectural identity that persists today. New Orleans reflects the functional, gridded rationalism of colonial town-making, shaped by climatic necessity and Creole adaptation. Washington D.C., on the other hand, is the grand-scale expression of ceremonial urbanism, shaped by French Baroque ideals but applied to a new republic, where power would be housed not in a palace but in civic institutions.

📍 From Grids to Courtyards — Colonial Housing Adapted for Climate and Culture and Courtyard Houses, Arcades, and Galleries Blending French with Caribbean Adaptations—French domestic architecture traditionally emphasized inward-facing courtyard houses, especially in the southern towns of Avignon and Montpellier, where narrow plots and thick walls moderated Mediterranean climates. In New Orleans, these forms arrived not just through the architects of France but through the migratory exchanges of empire—with architectural DNA shaped by Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), Guadeloupe, and Saint-Louis (Senegal). New Orleans was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, under the authority of the French Crown and the Company of the Indies, and laid out by engineer Adrien de Pauger in 1721. De Pauger’s plan followed the orthogonal grid system favored in French colonial towns, aligning with military and administrative models developed by Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, Louis XIV’s chief military engineer. The plan featured a rectilinear street layout, central civic plaza (Place d’Armes, now Jackson Square), and uniform lot divisions—echoing the planning templates used in French Caribbean colonies like Cap-Français (Haiti) and Saint-Louis, Senegal.

What arrived in New Orleans was not just form, but state-directed planning ideology. The 1721 grid—adapted to a soft, low-lying riverfront site—was overlaid with architectural responses drawn from the French and Caribbean experience. The Creole townhouse, which became the defining urban typology of the French Quarter, fused this administrative planning order with climatic pragmatism. These homes, tall and narrow, were aligned tightly within their blocks, often featuring central courtyards, arcaded ground floors, ironwork balconies, and pitched tile or slate roofs adapted for heavy rains and ventilation. Unlike the grand stone hôtels particuliers of Paris, the Creole townhouse was a product of imperial pragmatism—balancing French spatial logic with the hybrid material culture of empire. Its pastel-colored plaster walls, tall shuttered windows, and shaded galleries reflect African craftsmanship, Caribbean color sensibilities, and Spanish building regulations—all within a spatial framework first laid out by French colonial planners. These homes weren’t scattered organically—they were built within a deliberately gridded system that privileged walkability, density, and civic visibility. The uniformity of parcels allowed for efficient taxation and military control, but their architectural evolution revealed a much looser negotiation between regulation and adaptation. The result was a built environment that held tight to French geometry but absorbed Creole fluidity—creating what is now one of the most resilient and distinctive urban housing landscapes in North America.

On the left: The map above, titled Plan de la Nouvelle-Orléans, is a 1764 engraving by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin, one of France’s most prominent Enlightenment-era cartographers. Based on Adrien de Pauger’s original 1721 plan, the map illustrates the precise orthogonal grid that laid the foundation for what is now the French Quarter. Bellin’s map not only preserves this urban logic but also marks it as a significant example of 18th-century French colonial statecraft. The layout consists of a compact rectilinear grid approximately 11 blocks wide by 6 blocks deep, with each block measuring around 300 feet by 300 feet. Streets within the Quarter are relatively narrow—typically 30 to 35 feet wide—creating a dense, walkable fabric ideal for both shade and social interaction in a humid subtropical climate. The grid was designed for efficiency, visibility, and defense, organizing religious, civic, commercial, and residential functions around a central square—the Place d’Armes (now Jackson Square). Lots were typically subdivided to include inward-facing courtyard homes, forming a spatial typology suited to climate and cultural fusion. The scale of the Quarter reflects the priorities of a riverfront trading post: proximity, compactness, and modest urban infrastructure. Within this spatial framework, the Creole townhouse and climate-adapted courtyard typology emerged—not as informal vernacular, but as a direct architectural response to a formally imposed, rational French urban order.

On the right: The image captures the hybrid elegance of a Creole townhouse—a building type that exemplifies the adaptation of French planning ideals to the realities of life in colonial Louisiana. While rooted in French urban models—such as the enclosed courtyard townhomes of northern France or the Parisian multi-story houses of the 18th century—Creole architecture evolved into something entirely new in the New World. Unlike the fully imported British and Spanish building types, Creole houses were born of mixture: of French form, West Indian climate adaptations, African and Caribbean construction techniques, and Spanish colonial building codes. The townhouse’s distinctive features—flush street facades, iron balconies, rear service wings, and courtyards connected by porte-cochères—mirror the spatial hierarchy found in Parisian homes, yet its materials and layout respond to Louisiana’s humid climate, riverine landscape, and multicultural labor force. Similarly, the Creole cottage, with its high-pitched roofs, raised piers, and deep front galleries, drew on both Norman timber framing and Caribbean loggia traditions. Here, architectural theory met survival: houses were built to breathe, shade, and endure. Whether a plantation house near the Mississippi or a townhouse in the French Quarter, Creole buildings were designed within the 1721 orthogonal grid. The layout provided order; the architecture brought life. Together, they represent one of the only truly New World evolutions of colonial architecture—an inheritance of French Enlightenment planning tempered by Creole pragmatism, social complexity, and local climate.

By contrast, Washington, D.C. employs a vastly more expansive and symbolic interpretation of French planning principles. While L’Enfant also used a rectilinear base grid, his city was overlaid with radial avenues, circles, and ceremonial axes, producing a Baroque-inflected spatial composition reminiscent of Versailles. The typical city block in L’Enfant’s plan measures roughly 600 feet by 600 feet, or about four times the area of a New Orleans block. Streets and boulevards in Washington were designed to accommodate processions, monumental vistas, and federal authority—many exceed 100 feet in width. The city’s symbolic heart, the National Mall, spans over 1.9 miles (3 kilometers) from the Capitol to the Lincoln Memorial, reinforcing a visual narrative of democratic order through axial alignment. While New Orleans’ plan aimed to function within the physical and economic constraints of colonial trade, Washington’s plan was an ideological project—a spatial manifestation of the Enlightenment ideals of republicanism, civic hierarchy, and national identity. In essence, both cities were shaped by French spatial thinking, but executed with different scales, functions, and legacies in mind.

📍 Civic Squares and Social Geometry: From Place d’Armes to Jackson Square—At the heart of New Orleans lies Jackson Square, a public space that has anchored the French Quarter since the early 18th century. Originally named Place d’Armes, this civic square follows a logic laid down in France’s earliest examples of urban planning—particularly the Place des Vosges in Paris and Place du Parlement in Bordeaux. These spaces were defined by symmetry, enclosure, and order. They were not accidental voids, but carefully proportioned pauses in the urban rhythm. Designed for processions, markets, military drills, and political theater, French squares were both symbolic and practical—a place to gather, but also to reinforce civic identity. Jackson Square carries that same DNA. Framed by the St. Louis Cathedral, Cabildo, and Presbytère, and fronted by symmetrical Pontalba Buildings, it forms a spatial anchor for the French Quarter. The use of uniform façades, arcaded walkways, and a central green with walkways radiating outward echoes the ideals of Baroque spatial order. Unlike the wide avenues of Paris or Washington, New Orleans maintains a tight, walkable scale. Its streets draw you toward the square rather than away from it. That scale encourages interaction—between residents, architecture, and public life. As with the plazas of French port cities like La Rochelle or Marseille, New Orleans’ public square functions as a social condenser, binding city, religion, commerce, and daily routine into a coherent civic ritual.

This aerial view in the photo above of Jackson Square captures the enduring influence of French Baroque urbanism on American colonial planning, Jackson Square was designed as a symmetrical civic void, framed by harmonious façades and aligned with symbolic institutions. At its center is a formally planted green, ringed with paths that radiate outward in geometric order, recalling the controlled vistas and radial geometry found in French squares and gardens. The buildings surrounding the square reinforce its ceremonial structure: the St. Louis Cathedral sits squarely on the central axis, flanked by the Cabildo and Presbytère, which once housed colonial government offices and legal courts. Opposite them, the Pontalba Buildings provide rhythmic, arcaded façades that echo the uniform building fronts of Paris’s aristocratic squares. The design is no accident—it reflects the early 18th-century planning ideals brought by Adrien de Pauger, who laid out New Orleans in 1721 under French colonial authority. In this image, the square’s geometry is clearly visible: a carefully proportioned civic centerpiece, compact and accessible, integrated into the walkable grid of the Vieux Carré. Jackson Square offers a more intimate civic experience, rooted in the social geometry of French port towns, yet adapted for the Creole, Catholic, and commercial rhythms of New Orleans life.

This differs sharply from other U.S. colonial cities, such as Philadelphia or Savannah, whose British planners favored larger blocks, wider boulevards, and a separation of civic functions. Philadelphia’s rational grid, while innovative, spread public institutions across a sprawling layout, diluting their symbolic focus. Savannah’s squares, while frequent, emphasized modular repetition rather than formal centrality. Spanish colonial cities like St. Augustine were often planned according to the Laws of the Indies, prioritizing military control and ecclesiastical hierarchy. In contrast, Jackson Square integrates layers of urban life into a single, harmonized space that promotes walkability, interaction, and civic ritual. Even Boston’s organic street pattern—born of pre-existing paths and topography—lacks the formal geometry and symbolic clarity that define Jackson Square. What makes the French approach in New Orleans so distinct is that it brings the elegance and ceremony of European plaza-making into a colonial port town, scaled for intimacy but structured for authority. It is less about grandeur, more about rhythm, proportion, and spatial civility.

📍 The Last French City — Why New Orleans Endures When Others Faded—While cities like Detroit, St. Louis, and Mobile began as French settlements, New Orleans remains the only major American city where French planning, architecture, and cultural logic have endured at scale. What accounts for this rare survival? First, New Orleans’ geographic isolation and its strategic role as a port city helped preserve its original form. Unlike Midwestern French-founded cities that industrialized rapidly and overbuilt their colonial cores, New Orleans grew incrementally. Its tight orthogonal grid—laid out in 1721—remained functional even as the city expanded. This slower growth allowed preservation to coexist with evolution, rather than being erased in the name of progress. Second, the city's character was shaped by cultural layering, not replacement. French planning ideals were filtered through Spanish rule, African craftsmanship, and later Creole and Cajun adaptations. The result is an urbanism that’s hybrid yet cohesive, where French language, legal codes, and land-use practices remained embedded in the fabric of daily life. The French Quarter’s endurance owes as much to its mixed-use zoning, pedestrian-friendly density, and social rhythm as it does to its iron balconies and pastel façades. Third, New Orleans resisted the full force of 20th-century urban modernization. While other American cities bulldozed historic neighborhoods for highways and glass towers, New Orleans became a pioneer of preservation. Early efforts to protect the Quarter culminated in the creation of the Vieux Carré Commission in 1936, one of the country’s first legal mechanisms to protect a historic district’s architectural integrity. Crucially, the French Quarter was never fossilized—it remained a living neighborhood, populated by residents, artists, musicians, and merchants. In the diptych above — Left: This bustling French Quarter street scene—with French signage, preserved façades, and pedestrians—reveals a city still animated by the rhythms of its past. Unlike other former colonial cities where heritage is either staged for tourism or erased by development, New Orleans lives its French legacy daily—in its architecture, laws, celebrations, and street life.

In the diptych above — Right: This image shows the signage at the headquarters of the Vieux Carré Commission (VCC), one of the oldest historic preservation bodies in the United States. Created by the Louisiana State Legislature and enshrined in the New Orleans City Charter, the VCC was a direct response to growing concerns that the French Quarter—then under threat from modernization and demolition—would lose its unique architectural and cultural identity. The tipping point came as developers eyed historic buildings for parking lots, high-rises, and hotels. Civic advocates pushed back, recognizing the value of preserving not just individual structures but the entire urban fabric of the Quarter. The Commission was granted unusual authority for its time: the legal power to regulate the exterior appearance of buildings within the Vieux Carré (the original city footprint laid out by French colonial planners). This was not just about aesthetic control—it was about protecting the integrity of a living, functioning neighborhood whose architecture, materials, and scale told the story of a unique cultural heritage. The Commission’s jurisdiction covers the design, construction, alteration, maintenance, and even signage on any building in the district, requiring that all visible changes be reviewed and approved. What makes the VCC distinctive is that it governs an urban space that is still in use—not a museum or reconstructed village. The French Quarter remains a vibrant, evolving neighborhood with residents, businesses, music, religious processions, and political demonstrations. The Commission helps ensure that change happens within a framework of continuity. Unlike many U.S. cities where historic areas were sacrificed to highways or zoning-based redevelopment, New Orleans formalized preservation as a civic priority early on. Today, the VCC continues to operate under the Department of Safety & Permits in New Orleans. It plays a daily role in maintaining the district’s visual and structural authenticity, fielding permit requests for everything from paint colors to ironwork repairs. While tourism has brought both opportunity and pressure, the VCC acts as a stabilizing force—balancing growth with preservation. Nearly a century after its founding, it remains a key reason why the French Quarter still looks, feels, and functions like the last great French city in America.

St. Louis reflects French colonial grid planning rooted in trade and frontier settlement, unlike Washington, D.C., which showcases French Baroque ceremonial geometry, and New Orleans, which blends French and Caribbean influences in a denser, more organic colonial urban fabric. St. Louis employs a rectilinear French colonial grid with uniform parcels and axial alignment, optimized for riverfront trade, modular land division, and civic structuring—reflecting pragmatic adaptations of bastide planning principles to a flat, commercial frontier context.

📍 Foundations in the Frontier: The Bastide Logic Behind St. Louis’ Colonial Grid—St. Louis was founded in 1764 by Pierre Laclède, a French fur trader, and his stepson Auguste Chouteau, who together selected a site on the west bank of the Mississippi River to serve as a new trading post for the Louisiana Territory. But what they built was more than a trading depot—it was a planned colonial settlement, grounded in urban design principles deeply rooted in French military and civic planning traditions. The town’s layout followed a regular orthogonal grid, deliberately anchored around a central plaza and Catholic church. This mirrored the structure of French bastide towns like Monpazier and Aigues-Mortes, which had emerged in the 13th and 14th centuries across southwest France. These medieval planned towns were designed for both defense and governance, featuring a central open square that served as a marketplace and civic gathering space, with churches or town halls placed at or near the center. Their rectilinear street grids allowed for organized land division and future expansion, while also facilitating surveillance and military maneuvering. In colonial St. Louis, this logic translated to a settlement that was compact, clear, and civic-minded. The grid ensured efficient land use and access to the riverfront, essential for the fur trade. The placement of the Catholic church—a key institution in French colonial life—signaled the town’s cultural and spiritual orientation. Around the central square, civic and economic life unfolded, reinforcing the notion of an ordered community in what was otherwise considered frontier territory. This planning model wasn’t unique to St. Louis; similar layouts had been employed in Quebec City and New Orleans, both products of French colonial urbanism. But St. Louis was distinctive in its geographic isolation and in how successfully this spatial logic endured. While later waves of development and industrialization transformed the city, traces of the original plan remain visible in Laclede’s Landing, where the street grid still follows the early plat drawn under Laclède’s direction. Even after centuries of growth and upheaval, the DNA of French urban rationalism survives—a geometric imprint of colonial ambition, civic structure, and the belief that even in the wilderness, a city could be founded on clarity, center, and communal life.

In the photo above, Laclede’s Landing, St. Louis —This historic street preserves the layout of the city’s original French colonial grid. Inspired by the bastide towns of southern France, the narrow blocks and axial clarity remain visible today, framed by 19th-century brick buildings and shaded by trees. In the distance, the Gateway Arch rises—a symbol of westward expansion layered over a colonial urban core. Bastide towns are a distinctive form of planned medieval settlements constructed primarily in southwest France during the 13th and 14th centuries. Developed especially under the reigns of King Louis IX of France (Saint Louis) and King Edward I of England—at a time when parts of France were under English rule—these towns were instruments of economic expansion, strategic control, and civic organization. Originally, the term “bastide” referred broadly to any fortified structure or settlement, but over time, it came to specifically denote the planned towns founded in southwestern France during the 13th and 14th centuries, often under royal or seigneurial charters. These towns were not necessarily militarized fortresses but rather strategic urban foundations that promoted settlement, trade, and governance in frontier or contested regions. So, while bastide originally implied defense, its later use in urban planning emphasized rational design, civic order, and economic function as much as physical protection.

📍 Planning the Frontier: How a Medieval French Town Shaped the Bones of St. Louis—The two stacked photos—Libourne above and Cordes-sur-Ciel below—illustrate the shared spatial DNA of bastide planning, despite their contrasting topographies and historical contexts. The bastide town that most closely parallels St. Louis in terms of urban planning principles, orientation, and founding intent is likely Libourne, founded in 1270 by King Edward I of England near the confluence of the Dordogne and Isle rivers in southwestern France.. Bastide towns were defined by a set of distinctive urban features that set them apart from the irregular medieval settlements of their time. Most notably, they followed a regular orthogonal grid layout, which was highly unusual in the 13th and 14th centuries. At the heart of each bastide was a central square or “place”, often surrounded by arcades, which functioned as the social and economic core of the town. Churches and town halls were typically located directly adjacent to this square, reinforcing the integration of civic and spiritual life. Like St. Louis, Libourne was laid out on flat land using a regular orthogonal grid, a defining trait of bastide planning. Both grids were designed to allow for equal-sized plots, future expansion, and straight streets, supporting civic order and real estate control and laid out to promote clarity, expansion, and defensibility. Unlike hilltop bastides like Cordes-sur-Ciel or Najac, Libourne and St. Louis were both founded more for economic integration and governance than for military defense. Their commercial priorities shaped their scale, geometry, and urban hierarchy.

Bastides were designed to encourage market activity, civic order, and reliable tax revenue, often built rapidly—sometimes within just a few months—under royal or feudal charters to assert territorial control and stimulate development in contested regions. In St. Louis, many of the core principles of bastide planning were effectively translated into the colonial context. St Louise adopted a rectilinear grid oriented along the Mississippi River, echoing the rational geometry of medieval bastide towns. Although the natural topography and commercial priorities shaped some variations, the plan included equal-sized plots and straight, organized streets that facilitated expansion and trade. Libourne features a central marketplace surrounded by arcaded buildings and civic institutions—typical of bastides. St. Louis’s early plan also revolved around a civic and religious center, with the Catholic Church as a spatial anchor, while public gathering spaces supported commerce and governance. This early grid promoted market activity and civic cohesion, aligning with the bastide emphasis on orderly development and local control. While St. Louis lacked a fully arcaded square, its design nonetheless embodied the bastide ideals of clarity, utility, and strategic positioning, adapted to the demands of a growing colonial outpost on the American frontier.

While Cordes-sur-Ciel may symbolize the aesthetic and defensive ideals of medieval bastide towns, Libourne stands as the closest functional and spatial match to St. Louis. The contrast between Cordes and St. Louis reveals the remarkable flexibility of French urban planning principles and how they were adapted to suit vastly different geographic, political, and economic contexts. Cordes-sur-Ciel, founded in 1222 during the aftermath of the Albigensian Crusade, was built with defensibility and visual authority in mind. Perched atop a steep hill in southern France, its layout conforms to the contours of the terrain, resulting in curving streets and irregular blocks. Though it follows the bastide emphasis on centralized civic space, its planning was shaped by the need for military oversight and physical protection. The town’s hilltop position served as both a watchpoint and a symbolic assertion of control, with fortifications embedded in the urban form. Its beauty—narrow alleys, stepped streets, and panoramic views—is a byproduct of its defensive siting rather than a goal of aesthetic design per se. By contrast, St. Louis is on the flat floodplain of the Mississippi River and planned to serve as a commercial and colonial outpost where access to trade routes, civic order, and regular lot division were prioritized over defense. In essence, Cordes-sur-Ciel and St. Louis illustrate two poles of bastide urbanism: one defensive and dramatic, the other rational and expansive—each tailored to its historical moment and geopolitical role.

📍 Echoes of a French Footprint: Laclede’s Landing, the Vanishing Grid, and the Shadow of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial—As St. Louis evolved from a modest fur-trading post into one of America’s largest industrial hubs, the physical traces of its French colonial origins steadily eroded. The original town was laid out along the western bank of the Mississippi River following French colonial norms: a compact orthogonal grid, narrow lots oriented toward the water, and a communal focus around the Catholic Church and central market. This early plat reflected not only a practical response to the riverine terrain, but also a cultural worldview—one that valued walkability, civic integration, and shared natural access. But as the United States expanded westward in the 19th century, St. Louis rapidly transformed into a logistical and industrial powerhouse. Steamboats, railroads, and later highways reshaped the city’s priorities. Tight colonial lanes gave way to wide boulevards; modest French-style parcels were consolidated into sprawling commercial and industrial blocks. In the 20th century, sweeping urban renewal—often championed as progress—further erased the city’s colonial past. Entire neighborhoods were demolished, and the historic river-facing orientation was severed by expressways and modern development.

The most symbolic rupture came with the creation of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial (now home to the Gateway Arch) between the 1930s and 1960s. In preparing the site, the federal government razed more than 40 blocks of historic riverfront structures—many built directly atop the original French grid. Ironically, in celebrating American westward expansion, the project obliterated the French colonial foundation from which that expansion began. Only in Laclede’s Landing, just north of the Arch grounds, do traces of that original layout survive. Narrow lanes, irregular street alignments, and tightly spaced lots subtly defy the Jeffersonian grid that defines most of the Midwest. The area mirrors old French port cities like La Rochelle or Saint-Malo, and like Old Montreal, it preserves a colonial spatial logic amidst modern growth. Though the skyline has changed, the land logic of a French-American frontier town remains legible—offering a rare, living imprint of St. Louis’s origins.

Laclede’s Landing survived not by design, but by being just out of reach—physically, economically, and historically—of the forces that obliterated the rest of colonial St. Louis. Today, it serves as a rare, if partial, spatial memory of the city’s French origins. Laclede’s Landing lies immediately north of the Gateway Arch grounds (shown in the photo above), just beyond the boundaries of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial project. Its proximity to the river and its slight removal from the central area designated for clearing meant it narrowly escaped the wholesale demolition that reshaped the heart of the city in the mid-20th century. Unlike residential neighborhoods that were seen as "blighted" and targeted for clearance, Laclede’s Landing had already transitioned into a warehouse and light industrial district in the 19th century. Its buildings were functional and profitable for shipping, warehousing, and manufacturing—uses that kept the area commercially relevant well into the 20th century. Because it was economically useful, there was less pressure to demolish it. Finally, by the time large-scale preservation movements gained traction in the 1970s and 1980s, Laclede’s Landing had become recognized as a remnant of St. Louis’s early history. Civic leaders and urban planners began to see its potential for heritage tourism, adaptive reuse, and riverfront revitalization. It was designated as a historic district, and developers began repurposing the surviving 19th-century warehouse buildings into restaurants, offices, and entertainment venues.

Detroit stands apart in its French influence—unlike D.C.’s ceremonial plan, St. Louis’s grid overlay, or New Orleans’s preserved core, it fuses rural ribbon farms with Baroque geometry, creating a hybrid civic form where agrarian equity and Enlightenment order co-exist in the very bones of its evolving urban landscape.

📍 From Farms to Avenues: How French Land Divisions and Radial Ideals Shaped Detroit’s Early Urban DNA—Detroit’s planning legacy begins not with industry or automobiles, but with a French colonial idea of land. Founded in 1701 by Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac as Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit, the early French settlement along the Detroit River was structured around a system of ribbon farms—a distinctive land division method brought from France and adapted across New France. These long, narrow plots extended inland from the river, ensuring each landowner access to water for transportation, irrigation, and fishing, while providing space for agriculture deep into the forest. This pattern draws on medieval land practices from Normandy and Alsace, where narrow fields extended from roads or rivers to maximize equity and efficiency. In North America, this system was replicated not only in Detroit but also in Quebec City, Vincennes (Indiana), and Kaskaskia (Illinois). What made ribbon farms unique was their prioritization of equity over geometry—each settler received access to vital resources rather than a standardized block. Although Detroit would later develop an industrial grid, the ghost of these ribbon farms lingers. Streets like Conner Avenue, St. Jean Street, and Livernois still trace original plot lines, curving subtly or stretching in narrow north-south bands. These patterns created a layered urban palimpsest, shaping transportation routes, land value, and neighborhood formation. Unlike cities that erased their colonial footprints, Detroit preserved traces of its rural French DNA, embedded within its industrial frame.

The above triptych (left image)—Aaron Greeley’s 1810 Map of Private Claims—visually captures this system. Most farms were two or three French arpents wide (1 arpent = 191.831 feet), though some reached five. All were forty arpents deep—about 1.5 miles. Borders were marked by ditches, forming a highly legible rural mosaic. What makes this map even more remarkable is the star-like form near the center: the imprint of Judge Augustus B. Woodward’s 1805 radial plan, proposed after the fire that destroyed much of Detroit. Inspired by L’Enfant’s design for Washington, D.C., and French Baroque ideals seen in Place de l’Étoile and Versailles, Woodward rejected the grid in favor of geometric order and visual hierarchy. His plan centered around Grand Circus Park, a semicircular plaza from which Woodward Avenue, Griswold, and Adams radiated outward like spokes. Instead of rigid rectangles, he proposed equilateral triangles, circles, and hexagons—modular units meant to anchor neighborhoods in shared civic space. Though never fully implemented due to landowner resistance and the constraints of the existing ribbon farms, traces remain: non-standard intersections, radial boulevards, and the enduring presence of Grand Circus Park. Woodward’s vision became Detroit’s first urban philosophy—a fusion of French spatial tradition and Enlightenment ideals, reshaping not only how the city functioned, but how it signified meaning through space.

The above triptych traces the enduring geometry—and visible transformation—of Detroit’s Grand Circus Park over the past century. The center image, a 1920s black-and-white aerial photograph, captures the park at a moment when Woodward’s radial plan was fully legible and intact. The semicircular green space is framed by a dense urban fabric, with tightly packed mid-rise buildings and fine-grained street edges that reinforce the symmetry and ceremonial intent of the plan. The pathways within the park—radiating from central fountains and terminating at intersections—reflect the influence of French Baroque models like Versailles and Place de l’Étoile. By contrast, the right image, a contemporary aerial view, reveals what has been lost. While the radial structure remains, the urban enclosure has eroded: several key buildings have been demolished, leaving gaps and surface parking lots where continuous street walls once stood. The fine grain of the early 20th-century city—with small-scale retail, pedestrian-scaled blocks, and layered civic life—has given way to larger footprints, empty lots, and automobile infrastructure. Comerica Park and adjacent developments now dominate the skyline, altering the texture and scale of the area. Yet despite these changes, the bones of the plan endure. Woodward Avenue continues to cut through the city as a ceremonial spine, and the curved outline of Grand Circus Park still anchors the urban core. Together, these images reveal both the fragility of urban form and the resilience of foundational ideas—offering a rare glimpse into how 19th-century ideals of order, symmetry, and public space can survive, even as the surrounding city evolves or recedes.

📍 Geometry After Fire: How Woodward’s Radial Plan Reframed Detroit’s French Colonial Foundations—In the wake of Detroit’s devastating fire of 1805, the city faced more than just physical destruction—it faced a question of identity. Stepping into this vacuum, the Woodward plan was instrumental in sharing a radical rethinking of the city’s future, one that layered Enlightenment ideals over its existing French colonial form. Rather than erase the landscape of ribbon farms that had defined Detroit’s earliest logic, Woodward sought to impose a rational, geometric order atop it—a plan as visionary as it was impractical. At the center of this new vision was the hub-and-spoke model which in urban planning refers to a design in which major streets or avenues radiate outward from a central point, much like spokes on a wheel radiating from the hub. The "hub" is Grand Circus Park—a central, semicircular public space, and the "spokes" are the broad avenues like Woodward Avenue, Griswold Street, and Adams Avenue, which extend outward from that central point, connecting to other parts of the city. This hub-and-spoke model—anchored by Woodward Avenue and intersected by streets like Griswold and Adams—was rare in American urbanism at the time. Woodward’s plan took these monarchical tools and reinterpreted them for a republic. Rather than place a palace at the center, he positioned civic life itself—commerce, circulation, congregation. Unlike the rigid Anglo-American grid, his design embraced circles, equilateral triangles, and hexagons, forming a modular logic for public space and neighborhood development. Though the full plan was never realized—thwarted by landowner resistance and the stubborn geometry of the ribbon farms—it left lasting marks. Non-orthogonal intersections, open plazas, and the enduring orientation of streets toward Grand Circus Park speak to the staying power of that moment. Detroit, in this sense, became a layered city—a place where colonial pragmatism and post-Enlightenment symbolism collided and, in rare places, coalesced. The radial logic of Woodward’s plan did not erase the French foundations; it reframed them. And in doing so, it gave Detroit a civic structure that was neither fully European nor fully American—but something altogether new.

While Woodward’s radial plan was uniquely tailored to post-fire Detroit, its influence extended symbolically to broader conversations about civic form in the United States. Though not widely replicated in its exact layout, the plan became part of a lineage of American cities shaped by French spatial ideals, especially through its synthesis of Baroque geometry, Enlightenment rationalism, and republican civic order. It echoed and reinforced the precedent set by L’Enfant’s design for Washington, D.C., which had already introduced the idea of a ceremonial capital laid out in radial avenues and symbolic axes, adapted from Versailles and Paris. In cities such as Indianapolis (1821) and Buffalo (1804), similar spoke-and-wheel layouts were proposed—often with a central circle or plaza, grand avenues, and modular blocks arranged with geometric logic. Though not always attributed directly to Woodward, these efforts emerged in a cultural atmosphere increasingly open to French and continental European planning principles, often in response to fire, rapid expansion, or the desire to project civic ambition. The fact that Detroit attempted to layer a radial scheme over French agrarian ribbon farms—rather than starting with a tabula rasa—made it a rare case of planning over precedent, not in spite of it. More subtly, Woodward’s plan empowered French colonial urban legacies by proving they could be reframed rather than replaced. In an era when most U.S. cities gravitated toward the Jeffersonian grid—a land division and town-planning system based on a uniform, rectilinear grid which is a hallmark of American expansion in the 18th and 19th centuries, Detroit stood apart—offering a hybridized model rooted in French pragmatism and formal geometry. Though American urbanism would largely favor gridded efficiency in the 19th century, Detroit’s example showed that French spatial logic could endure, adapt, and even be elevated—giving shape to a uniquely American form of civic monumentality without monarchy.

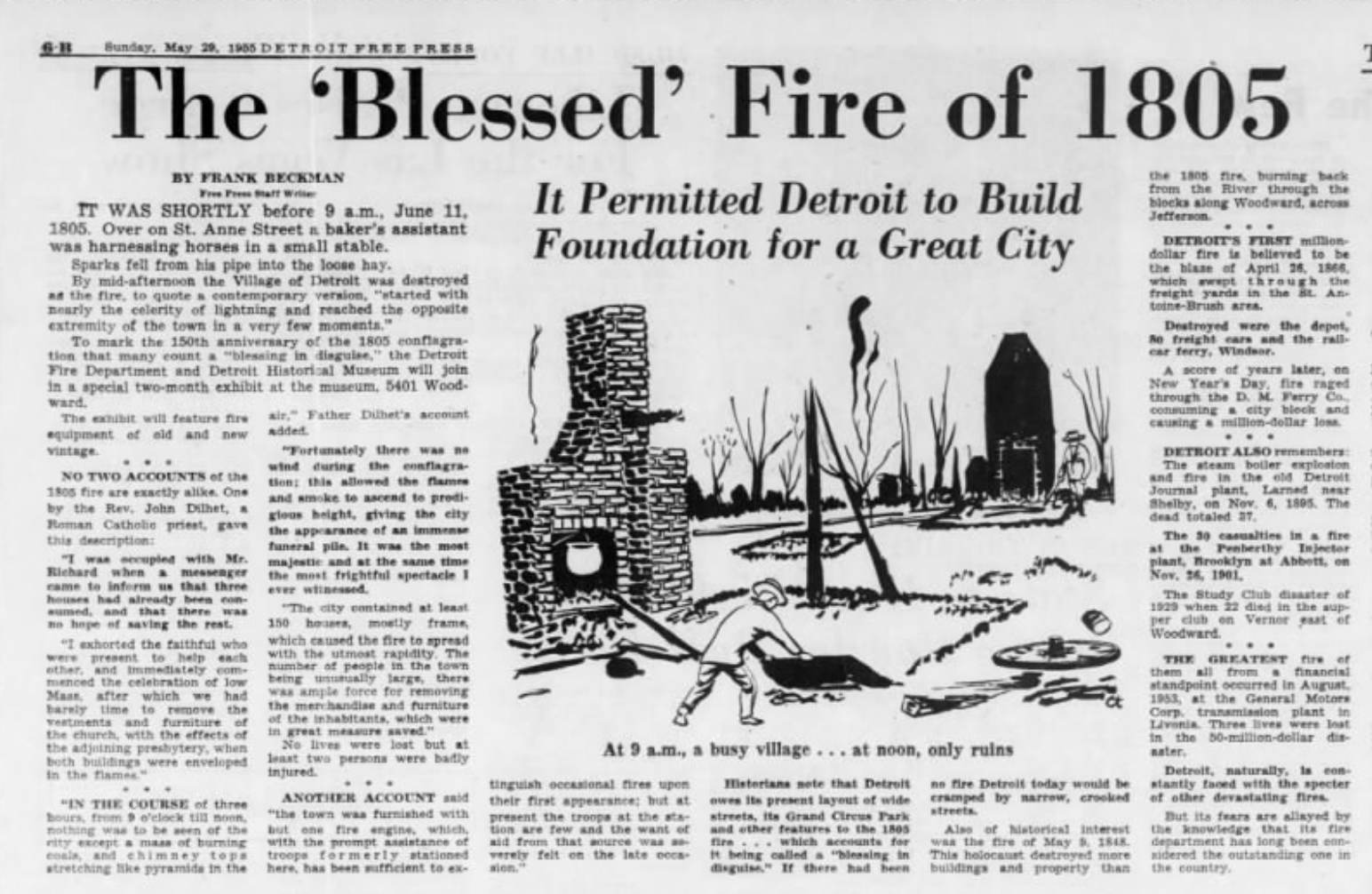

The photo above shows an archival newspaper article—published on the 150th anniversary of the 1805 Detroit fire—frames the city’s destruction as a paradoxical gift: a "blessing in disguise" that allowed for the creation of a radically new civic order. Featured prominently is the idea that the fire cleared the way for Woodward’s visionary radial plan. The article reinforces how deeply the fire was understood not only as a physical rupture, but as a philosophical reset: an opportunity to layer Enlightenment rationality over French colonial pragmatism. This calm visibility of destruction allowed observers—and soon, planners—to see not just what had been lost, but what might now be reimagined. The article concludes that “historians note that Detroit owes its present layout of wide streets, its Grand Circus Park and other features to the 1805 fire,” underscoring how spatial ideals drawn from European ceremonial design were translated into a new republican form. The accompanying illustration, showing the dramatic shift from "a busy village" to "only ruins," heightens the mythic narrative of rebirth through fire.

📍 From River Lines to Urban Layers: Rouen and Detroit’s Shared Urban Memory—We do not need to look far beyond the origins of the ribbon farm itself to find a precedent that mirrors Detroit’s experience. In the Seine Valley of Normandy, where the lanière system of long, narrow agricultural plots first took shape, we see how French rural geometry—designed for equity, access, and efficiency—endured across centuries and adapted to shifting urban conditions. Towns like Rouen evolved not by erasing their agrarian logic, but by layering new forms of civic order over it. As in Detroit, these narrow plots, originally aligned perpendicular to rivers or roads, became the framework onto which later civic, commercial, and infrastructural development was mapped. The result is a uniquely French urbanism—not one imposed upon the land, but grown from it—where Enlightenment planning ideals eventually merged with centuries-old patterns of land use. It is in this continuity, not rupture, that we find a deep parallel with Woodward’s Detroit: a city where the monumental aspirations of geometry and governance coexisted with the enduring traces of French colonial pragmatism.

The diptych above presents two sweeping views of Rouen, both captured from the hill of Sainte-Catherine—one a colored lithograph from 1846 titled Rouen seen from a balloon by Jules Arnout (left), and the other a contemporary photograph of the same urban landscape. Seen side by side, they offer a rare and precise lens into how French spatial logic endures, even as cities modernize and morph across centuries. In the 1846 lithograph, we see Rouen in its early industrial and post-Napoleonic phase, when the city was still deeply shaped by agrarian geometry and medieval boundaries. The Seine River serves as the dominant axis, with development hugging its banks in long, narrow strips—a clear legacy of ribbon farms (lanières) that once lined the valley. Streets run roughly perpendicular to the river, echoing these original land divisions. Rouen Cathedral rises at the center, its spire anchoring the skyline in an otherwise low-rise, fine-grained urban fabric. Despite steady urban growth, the city still breathes with the rhythm of its agrarian past, scaled to foot traffic, horses, and river navigation. By contrast, the 21st-century color photograph reveals a modern Rouen layered over that same enduring geometry. While high-rises, expanded bridges, and broad boulevards now frame the scene, the spatial DNA remains intact. The Seine continues to organize the city's form; the roads maintain their historic orientation; and the cathedral still commands both symbolic and visual centrality. The transformation is significant, yet the underlying logic persists. Like Detroit—where Woodward’s radial plan was layered onto a colonial fabric of French ribbon farms—Rouen demonstrates that urban evolution can emerge through adaptation, not erasure. In both cases, spatial order was not imposed wholesale, but grew from inherited systems: practical, equitable, and deeply embedded in the landscape. These two images remind us that French planning traditions were never static; they were resilient frameworks, able to absorb centuries of change while preserving coherence, hierarchy, and civic identity. Together, this Rouen diptych is more than a visual comparison—it is a quiet manifesto on how cities carry their past forward, sometimes subtly, always spatially.

“Understanding French planning’s layered legacy across American cities invites us to see not just where we’ve built, but how. In these spatial traces, we rediscover identity—not inherited, but drawn, lived, and continuously reinterpreted across centuries. These are not just design decisions; they are civic values inscribed in land—choices about equity, spatial order, and the relationship between people and place that still echo in the structure of our cities today.”

—OHK’s Annual Retreat, Portland 2025

This reflection guided our team retreat in Portland—an annual OHK tradition where we pause to interrogate urban form, community evolution, and our own design values. Each year, we select a city that challenges us to see the built environment with fresh eyes. Portland offered just that. While it bears few direct traces of French colonial planning, it reveals how French spatial logic—particularly its emphasis on equity, orientation, and layered civic space—can echo across time and place. We grounded our retreat in Ladd’s Addition (1891), a historic neighborhood in Southeast Portland that disrupts the city’s Jeffersonian grid with a surprising radial geometry. Centered on a traffic circle and four rose gardens, its spoke-and-diamond layout evokes Baroque ideals of hierarchy, legibility, and symbolic order. Though not modeled explicitly on Paris or Versailles, it shares their DNA: diagonal avenues, symmetry, and public space as an organizing force. In an American city known for its rational grid and progressive urbanism, Ladd’s Addition stands as a European inflection point—an elegant reminder that design can carry civic meaning even in residential contexts. For OHK, walking its streets became an embodied exercise in our own quote. The identity of a place, we saw, isn’t just inherited—it’s drawn, revised, and lived. In Ladd’s Addition, we witnessed how spatial ideas travel, adapt, and resurface—not through replication, but through resonance. The neighborhood’s quiet geometry invites us to rethink how civic values—beauty, orientation, connection—can shape even small-scale planning decisions. And it reminded us that sometimes, the most radical moves are the ones that restore depth, memory, and balance to the urban fabric.

While we focused on Detroit, Washington, D.C., St. Louis, and New Orleans, many other American cities still bear the imprint of French spatial logic. Places like Mobile (Alabama), Vincennes (Indiana), Kaskaskia (Illinois), Prairie du Chien (Wisconsin), Ste. Geneviève (Missouri), Natchitoches (Louisiana), and even parts of Green Bay (Wisconsin) and Baton Rouge (Louisiana) reflect French colonial land divisions, street patterns, or civic hierarchies. Though not explored here to preserve focus and readability, these cities remain compelling examples of how French planning traditions quietly shaped the American built environment—and merit deeper investigation in future work.

Our focus remained on cities where French planning formed the foundational urban logic—not places where French influence arrived later through architectural style or civic aesthetics. For this reason, cities like San Francisco, while rich in Beaux-Arts or Art Nouveau elements, were excluded from this analysis. These omitted cases still merit deeper investigation and may be explored in future work. OHK may consider producing a Part 2 of this article to address these overlooked but equally rich examples, extending the conversation about France’s spatial legacy in the United States.

At OHK, we help governments, cities, and real estate developers reimagine urban futures by reconnecting them with their foundational logics—whether colonial layouts, historic land divisions, or lost civic geometries. Our expertise lies in benchmarking, revitalization, and spatial translation: identifying the DNA of place and drawing it forward through contemporary design, infrastructure, and policy. From restoring the integrity of radial plans and waterfronts to weaving green infrastructure through historic cores, we specialize in projects that don’t overwrite the past but build upon it. Whether transforming a historic district or reactivating a forgotten civic axis, our work bridges time—delivering solutions that are spatially coherent, culturally rooted, and future-ready. Contact us to learn how we can help you realize the transformation of your city’s most valuable urban assets.