Saturday 02.18.17

Vocational Training Transformation in the Age of Global Brands

OHK's insights on building national qualification and vocational

excellence and the transformation of tradition (Part 1)

This blog post is the first of two parts. In this part, OHK’s Ahmed Hassan offers insights from Egypt on how entrepreneurs and successful businesses can help reform national and vocational qualification schemes and offers a tribute to an Egyptian nature activist who made a difference. Part two will describe a recent visit to the Azza Fahmy Design Studio, exploring the challenges and successes of its first few years in operation.

Egypt’s traditional forms of vocational training – ways to organize work and pass on skill – have persisted through the centuries and still exist today in jewelry and other handicrafts, where workers are ranked according to skill and work experience. In this system, An “Osta” is a Master, a “Sanaie,” is a Craftsman, and a “Sabi” is a young assistant or apprentice. This photo, taken on the 1000-year old Mu’ezz Street in Islamic Cairo, depicts five generations of one artisan family that has been making the “fanous,” a traditional decorative lantern that is the signature symbol of Ramadan and is believed to have originated in Fatimid Cairo. Photo © OHK Consultants

In 2005, I was closing out a consulting engagement in Egypt before heading back to Switzerland, where I was living and working at the time. I spent my final week on the Egyptian Red Sea advising the late Amr Ali, then the Managing Director of the Hurghada Environmental Protection & Conservation Association (HEPCA) and a well-known, international environmentalist. As we finished a long day of site visits interlaced with discussions around HEPCA’s future – my advisory was focused on repositioning HEPCA towards growth, diversity and financial independence – Amr suggested a dive at the Hamata Dolphin House. Amr had been occupied with a campaign to lessen the impact of heavy recreational diving on the Red Sea’s spinner dolphin population, focusing on two of their most important habitats: the Red Sea’s Samadai Reef (known in the diver community as "Dolphin House") and Sataya Reef.

This photo, taken in 2004, shows the famed mangroves of the South Red Sea region. At the time, I was drafting on behalf of the Egyptian government a plan for an ecologically-based zoning to preserve the marine and terrestrial ecosystems of highly sensitive coastal areas such as Hamata, Wadi Lahmi, Bernice, and Qulaan. Most women in local beachside villages like the one shown in the photo continue to adorn themselves with traditional jewelry. Photo © OHK Consultants

As we drove back to the resort town of elGouna – a resort development that I had helped strategize with a team of planners and economists from the World Bank a few years earlier – Amr asked me to join him for lunch the following day with a friend. We convened at a popular divers’ hangout in Hurghada, and I was introduced to Amr’s friend Fatma Ghali, the daughter of famed Egyptian jewelry designer Azza Fahmy. Fatma was helping her mother grow the family business, established in Cairo in 1969, from a local eponymous jewelry brand towards a global audience. Amr and I shared the work we were doing together to reposition HEPCA, and I reflected on some of my recent work in South Africa – efforts which I thought might interest a jeweler whose business depends upon skilled labor and apprenticeships. In 2001, I had been part of a team of international consultants and local specialists appointed to review the country’s National Qualification Framework (NQF). The NQF was the post-apartheid government’s effort to restructure its skills and qualification schemes towards national recognition of vocational skills outside of the formal education system, in recognition of the tremendous historical disparities in access to education.

Egypt’s Bedouin adornments are iconic for their functional, wealth-saving, and symbolic values. The antique veils of the Sinai Peninsula are extremely rare and feature traditional motifs, silver coins, and eclectic artistic flourishes. The one shown here, currently in the collection of the Ethnological Museum of Berlin, dates from the late 19th century. Photo © OHK Consultants.

Reflecting on the similar skills gaps in both Egypt and South Africa, I suggested that, absent a comparable push by the Egyptian Government to reform its education and training frameworks, private businesses like Azza’s that have accumulated skills are best positioned to set and measure skill qualifications. Our brainstorming over lunch led to a breakfast rendezvous the next day with the family of three: Azza, her daughter Fatma who today is the company’s Managing Director, and Amina Ghali, its head designer.

Azza Fahmy’s jewelry borrows from the entirety of Egypt’s history, ranging from ancient Pharaonic symbols and “falaheen” (peasant) wedding motifs to patterns of Islamic art and elements of more recent folklore and colloquial poetry. Photo courtesy of Azza Fahmy (David Degner).

Over coffee in the Four Seasons hotel in Giza, we dove into the discussion. I expanded upon my earlier brainstorming with Fatma, and emphasized that Egypt’s creative skill hubs like Azza Fahmy’s workshop should take a page out of South Africa’s book to build an internationally recognized vocational training scheme targeting underprivileged communities. Azza agreed, and asked what would be the strategy to do so. I outlined a five-point approach.

The millennium-old Khan el-Khalili is a major center of economic activity in the heart of the Islamic district of Cairo. The souk is home to Egypt’s largest concentration of jewelry and artisan workshops, and it is where Azza Fahmy started making her first designs in collaboration with master gold- and silversmiths. Despite the incredible richness of skill, the Khan still has no nationally recognized qualification system for its hundreds of artisans. Photo © OHK Consultants

Firstly, it is essential to approach this from a practical, on-the-job qualification perspective, similar to the apprenticeships found at a variety of German brands associated with craftsmanship. In this model, an apprentice goes through a “triple track," splitting their time among classroom lessons, vocational instruction and practice, and on-the-job internships at a company. There is no precise benchmark for quantifying this split, but I advocated to Azza that she should adopt something along a 15-70-15 split, in which 70% goes to vocational instruction and practice, with the remaining divided among classroom and internship components.

The Design Studio by Azza Fahmy is located in Al-Fustat, the first capital of Egypt, built in AD 641 and today a center of traditional crafts known for the diversity of its artisans and handicrafts. Photo © OHK Consultants

Secondly, Azza should promote a mix of both Egyptian trainers sourced directly from local production facilities alongside international masters of the craft. Egypt’s pedagogical systems, whether vocational or otherwise, have not appreciably evolved; this model would enhance and maintain the quality of training by bringing ideas, methods, practices, and skills from other countries. This not only provides an international caliber of training delivery but also allows innovation to enrich the program itself.

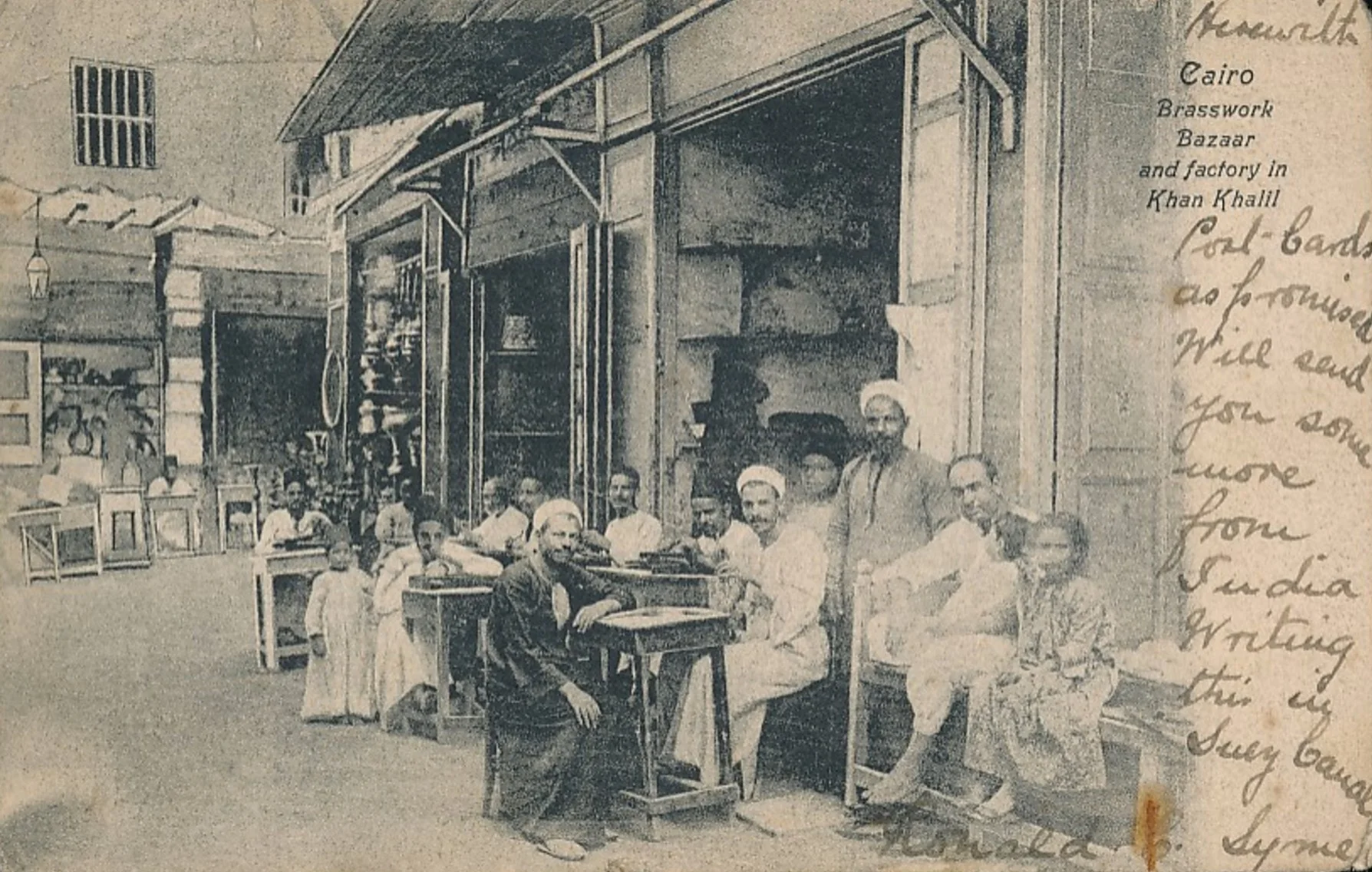

Artisans in Khan el-Khalili, 1908. © OHK Consultants Photo Archives

Thirdly, the apprenticeship program should be combined with a formal “school” organizational setup that is Azza-branded but is run as a “studio” entity separate from the jewelry business. I was careful to note the obsession in Egypt with lecture-based pedagogies, and that such a studio, though a school in name, should not fall into this pattern. The 15% classroom delivery component should still be delivered on production benches, in the spirit of creation rather than theory. The studio itself would be set up like a small factory – an annex to the actual production factory – which in turn can also host the 15% internship component and lead to a permanent job. In countries where talent identification is made even more challenging by a lack of a common qualification, such an apprenticeship can serve as a direct talent pool for its host companies.

Fourthly, the program must be a viable economic concern. Vocational training is rarely profitable but it should at least break even. The presence of international trainers enables the program to be attractive to more affluent aspiring artists in the local market who can afford an internationally-priced program. By marketing 6-month to 1-year qualification tracks to middle- and upper-income Egyptians – particularly fashion-focused entrepreneurs and artists – it is possible to build the consistent revenue needed to attract international instructors, maintain quality of delivery and facilities, and even compete with similar schools and programs overseas for global, paying apprentices.

Today, the Azza Fahmy studio is mostly run by young Egyptian women, a remarkable achievement in the male-dominated workshops of the Khan El-Khalili. The school attracts international artists as both teachers and apprentices, and is known not only for being part of a global namesake brand of a successful woman entrepreneur but also for being grounded in decades of artistry meticulously inspired by Islamic, Egyptian, and Bedouin jewelry and crafts. Photo © OHK Consultants.

Finally, the program must give back through a need- and merit-based scholarship program that unlocks apprenticeships to underprivileged Egyptians, especially women. Recently, The Telegraph described Azza as "an exceptional woman, who makes exceptional jewels in exceptional circumstances." To me, the exceptionalism arises from Egypt’s diversity, whether the artisans of the urban Khan el-Khalili or the rural communities which have inspired Azza’s great array of local styling, materials, designs, methods, and branding. The program should become Azza Fahmy’s tribute to the communitiesof Egypt, be it Nile Valley villages, the Bedouin tribes of Sinai, or the Nubians of Aswan, that served as inspiration for her iconic work. Such a scholarship only further underscores the importance of maintaining healthy financials, and using positive revenues to subsidize those of merit in need.

Despite millennia of artistry and excellence in the design and making of jewelry, ranging from Pharaonic finery to Cubist and Bauhaus styles, Egypt has only very recently enjoyed an artistry qualification scheme to reflect these contributions. In 2013, eight years after our discussion in the Giza Four Seasons, the Design Studio by Azza Fahmy was established as a collaboration between her brand and Alchimia, the contemporary jewelry school in Florence, Italy. The Azza Fahmy studio and school is located in the Al-Fustat area in old Cairo, among handicraft workshops dating to the 19th century.

I wrote this blog post to provide an example of how the private sector can shape vocational training and qualification. This can happen not just in handicrafts but across a variety of industries. Azza Fahmy’s journey to being the best-known jeweler in Egypt began in the 1970s with her own apprenticeship under the leading master jewelers of Khan el-Khalili. My chance encounter with her planted the seed for a truly world-class qualification system. This is a journey that can be replicated throughout the world.

The late Amr Ali, who introduced me to Azza Fahmy, was an “eco-warrior,” as he liked to be called. Eight years after our dive among the dolphin reefs of the Southern Red Sea, Amr Ali realized his ambition for HEPCA to take over management of this area in order to ensure the protection of Red Sea dolphins and their reef habitats against mass resort development, solid waste dumping, and unregulated recreational diving. Photo courtesy of HEPCA.

Ahmed is Managing Partner at OHK and regularly writes about strategy, entrepreneurship, design, and local development. Contact him to learn more.