Property Mass Valuation Systems: Frameworks, Classifications, and Typologies

OHK provides a primer examining mass valuation systems, comparing classifications, methodologies, and applications to support transparent, scalable, and data-driven property valuation globally.

This article is Part I of a two-part series on mass valuation systems. Part I focuses on how mass valuation systems are classified and the main system types observed in global practice. Part II shifts from classification to implementation, examining how governance, data realities, sequencing, and institutional design determine whether these systems succeed or fail in practice. From system types to system performance— Part I maps the landscape of mass valuation systems and how they differ by automation, method, data environment, and governance design. Part II builds on that foundation by explaining why some systems function credibly year after year while others collapse, stall, or lose legitimacy. You can read Part II here.

Reading Time: 30 min.

All illustrations are copyrighted and may not be used, reproduced, or distributed without prior written permission.

Why Mass Valuation Is Not One Thing

Mass valuation has become a central pillar of land administration reform, property taxation, and urban finance across the world. Governments increasingly rely on mass valuation systems to broaden tax bases, improve fiscal equity, support land markets, and modernize public administration. Yet despite its growing prominence, “mass valuation” is often discussed as if it were a single technical solution—a piece of software, a statistical model, or an automated pipeline that can be procured and deployed.

In reality, mass valuation is not one thing. It is a family of systems shaped by institutional mandates, legal frameworks, data environments, market maturity, and governance choices. Two countries may both claim to operate “mass appraisal,” yet one may rely on expert-defined schedules and manual reviews, while the other deploys automated valuation models updated annually through dense transaction data. Both are mass valuation systems, but they function very differently and serve different institutional realities.

This lack of clarity matters. Many valuation reforms struggle not because the underlying analytical methods are flawed, but because the chosen system type does not match the country’s data, capacity, or governance context. Overly ambitious automation, misapplied statistical models, or the uncritical import of foreign systems frequently result in outputs that cannot be explained, defended, or sustained.

This article seeks to clarify the landscape. It first explains the main ways mass valuation systems are commonly classified, then describes the principal system types observed in global practice, illustrating where and why each approach is used. Rather than advocating a single “best” model, the aim is to provide a structured understanding of options, trade-offs, and real-world patterns that can inform more realistic reform choices.

How Mass Valuation Systems Are Classified

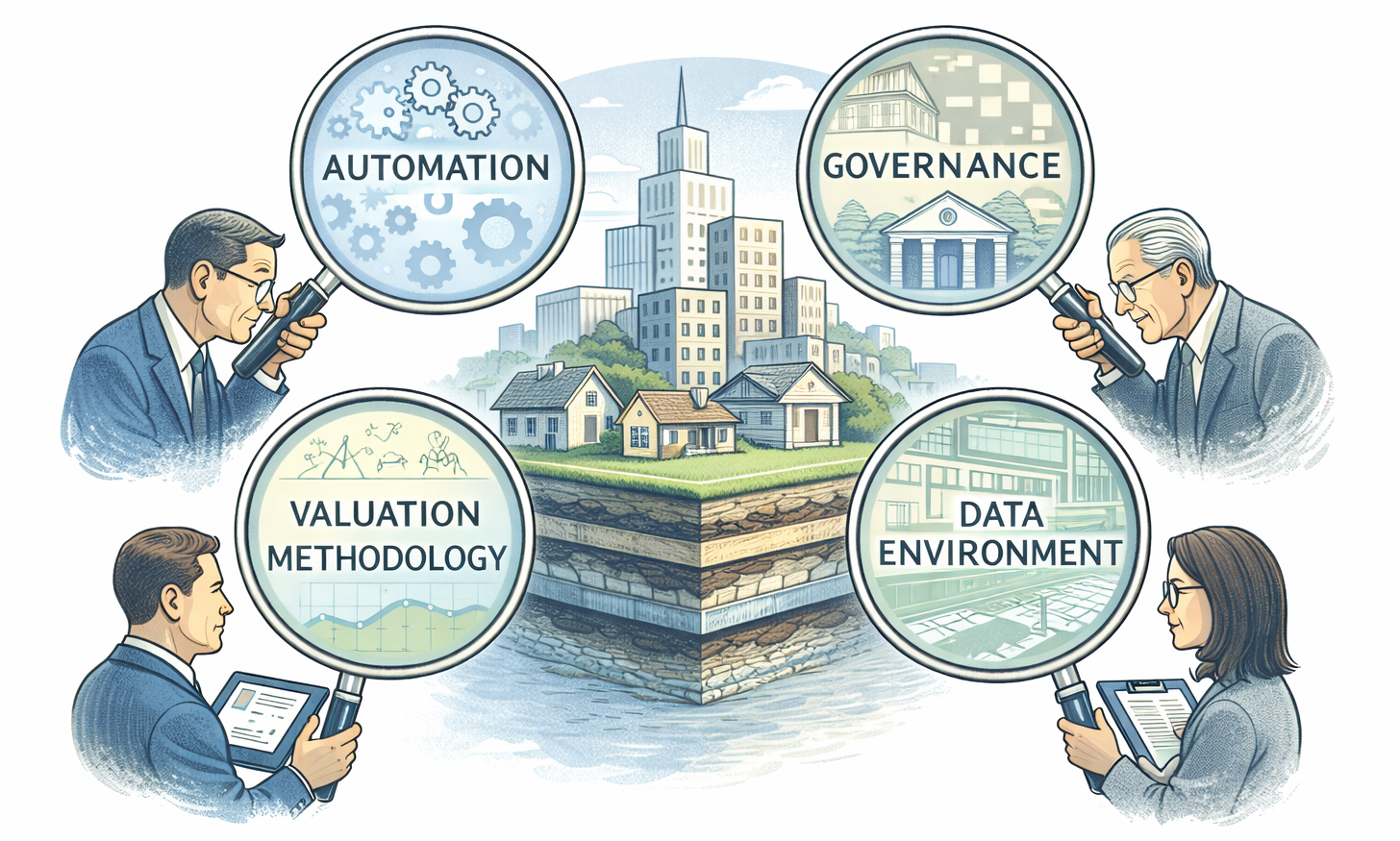

Mass valuation systems can be classified in several overlapping ways. No single classification captures all dimensions, but four lenses are particularly useful: level of automation, valuation methodology, data environment, and governance design. Together, these provide a practical framework for understanding why systems differ and how they evolve.

Mass valuation systems are not classified according to a single universal taxonomy; instead, they are understood through a small number of complementary classification lenses that reflect how such systems actually function in practice. In applied reform work, four core classification approaches are most commonly used: (i) level of automation, which describes how valuation decisions are distributed between models and human assessors; (ii) valuation methodology, which captures the analytical logic used to estimate value; (iii) data environment and market maturity, which determines what types of methods are feasible and defensible; and (iv) governance and institutional design, which defines where authority, accountability, and legal responsibility for valuation reside. These classifications are not mutually exclusive and are intentionally overlapping, as mass valuation systems are complex institutional arrangements rather than discrete technical products. Using multiple lenses allows practitioners to understand not only what a system does, but why it operates the way it does, how it can evolve over time, and where reform risks are most likely to emerge.

Classification by Level of Automation: The most common—and often the most misleading—classification is by automation. Systems are frequently described as manual, semi-automated, or fully automated. While useful, this framing oversimplifies reality.

Automation in valuation is not binary. Even the most advanced systems retain human decision points, particularly for quality control, exception handling, appeals, and policy oversight. Conversely, so-called “manual” systems often apply standardized logic consistently across thousands of properties, which is itself a form of mass processing. The presence or absence of software does not, on its own, define how a valuation system operates.

A more accurate way to think about automation is to ask where valuation decisions are made. In low-automation systems, experts directly determine values using schedules, zoning tables, or professional judgment, with limited computational support. In higher-automation systems, models generate baseline values across large property sets, while human assessors focus on supervising outputs, validating anomalies, and maintaining institutional accountability. The defining feature is therefore the distribution of responsibility between humans and systems, not the sophistication of technology alone.

Viewed chronologically, automation levels often reflect stages of institutional and data maturity rather than deliberate end-state choices. Many jurisdictions begin with manual or rules-based systems supported by basic tools such as spreadsheets, paper records, or simple databases. As data volumes increase and processes stabilize, valuation functions typically introduce Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal (CAMA) platforms, GIS integration, and statistical tools to improve consistency and efficiency. Only in contexts with dense transaction data, reliable digital registers, and strong governance frameworks do fully automated or AVM-driven systems become feasible and defensible.

Importantly, each automation level implies a different technology stack and operational requirement. Manual and low-automation systems may function effectively with limited software but require strong procedural discipline and institutional knowledge. Semi-automated systems depend on structured databases, parcel identifiers, GIS layers, and modeling tools, alongside trained staff capable of interpreting results. Highly automated systems require robust data pipelines, frequent updates, model monitoring infrastructure, and legal frameworks that support explainability and appeals. Progression along this spectrum is therefore less about acquiring more advanced software and more about aligning technology, data, and institutional capacity over time.

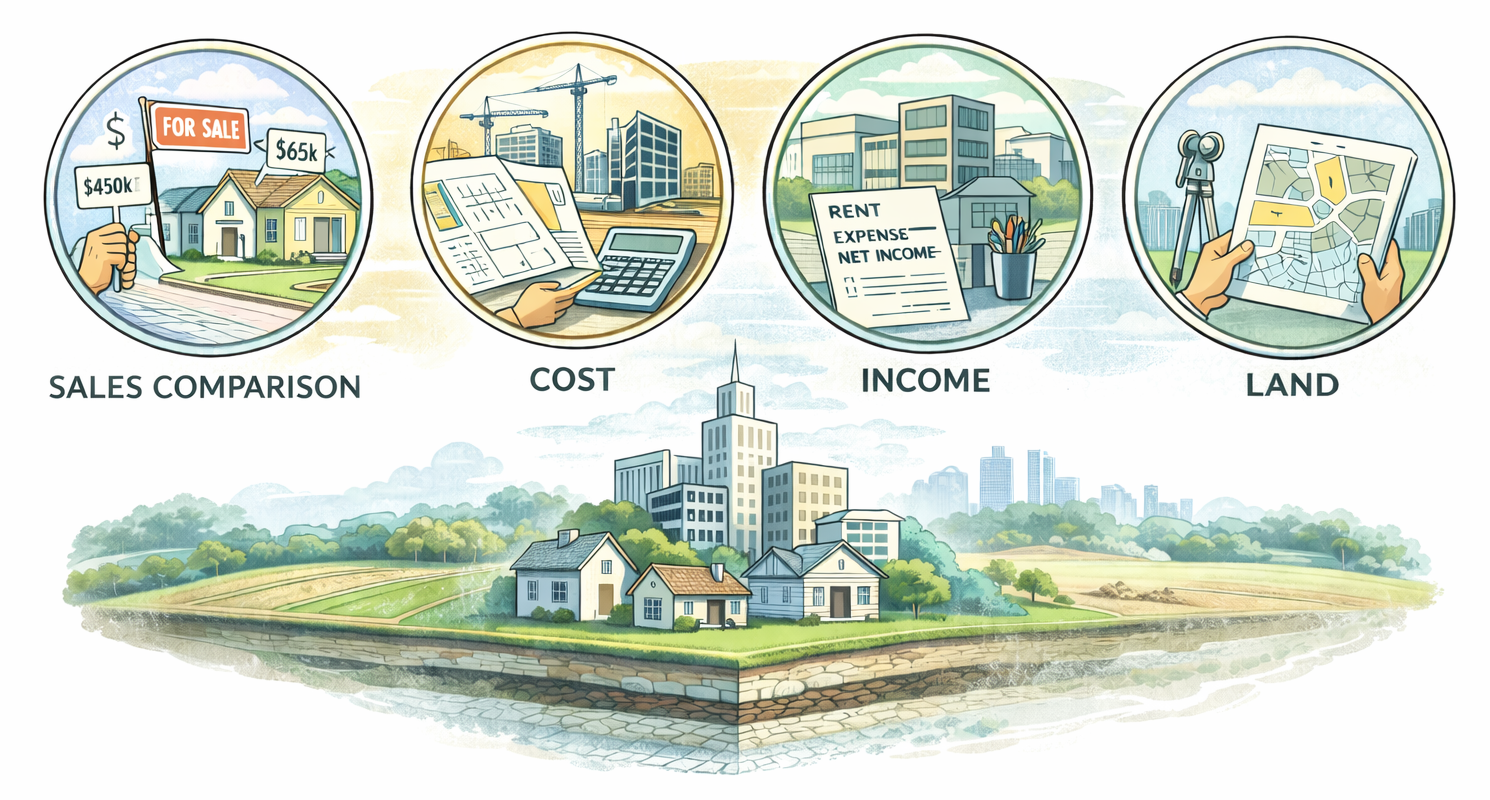

Classification by Valuation Methodology—A second lens is valuation methodology. Mass valuation systems may rely primarily on the valuation methodology that underpins value estimation. Methodology determines not only how values are calculated, but also what types of data are required, how sensitive results are to market volatility, and how easily values can be explained and defended.

In practice, valuation methods are chosen less for theoretical purity than for their compatibility with market structure, data availability, and legal expectations. As a result, most operational mass valuation systems apply different methodologies across property types or market segments, using each method where it performs best rather than forcing a single approach across heterogeneous conditions.

Sales comparison–based mass valuation relies on observed market transactions to infer value, typically through statistical or econometric modeling. This approach is most effective in active, transparent markets where sufficient sales data exists and property attributes are reliably recorded. By analyzing how characteristics such as location, size, and quality influence prices, sales-based models can produce responsive and market-aligned valuations. However, their effectiveness is constrained by transaction density, data quality, and the presence of informal or distorted markets. Where sales are sparse, underreported, or unrepresentative, sales-based methods can generate unstable or biased results. These methods are therefore enabled by strong transaction reporting systems and consistent property registers, and constrained in markets with informality or regulatory price distortions.

Cost-based mass valuation estimates value by combining land value with the depreciated replacement cost of buildings or improvements. This approach is particularly useful where market transactions are limited or unreliable, as it does not depend directly on sales evidence. Cost methods are often applied in emerging markets, for public or special-use properties, or as a stabilizing component within hybrid systems. Their strength lies in predictability and explainability, as construction costs and depreciation schedules can be standardized and documented. However, cost-based methods struggle to capture market preferences and locational premiums, and may diverge from actual market values over time if land values or depreciation assumptions are not updated regularly. Their effectiveness depends on credible cost schedules, realistic depreciation models, and at least a basic land value framework.

Income-based mass valuation is primarily applied to rental and income-generating properties, such as commercial buildings or multi-unit housing. This method estimates value by capitalizing expected income streams, using standardized assumptions about rents, expenses, and capitalization rates. Income approaches are well suited to property segments where income data is available and relatively stable, and where market participants price assets based on returns rather than physical attributes alone. In mass valuation contexts, income models are often simplified and applied by category or zone to ensure scalability. Their main constraint is data availability, as reliable rental and expense information is often fragmented or confidential. These methods are enabled by regulatory reporting, market surveys, or proxy indicators, and constrained where rental markets are informal or poorly documented.

Land-focused valuation approaches concentrate on estimating land values independently of buildings, often through land value zoning and standardized adjustments for accessibility, infrastructure, and use. This approach is particularly useful in rapidly urbanizing contexts, informal areas, or jurisdictions where building data is incomplete or unreliable. By anchoring valuation in location rather than structure, land-focused methods can provide a defensible basis for taxation or planning even when improvements are poorly documented. However, isolating land value from built value requires careful assumptions and may understate economic reality in built-up areas. These methods are enabled by basic spatial data and zoning logic, and constrained where land use regulations are unclear or enforcement is weak.

Taken together, these methodologies illustrate why mass valuation systems rarely rely on a single analytical approach. Methodological diversity is not a sign of inconsistency, but a pragmatic response to varying data conditions, market behavior, and institutional constraints. Effective systems deploy each method where it is strongest, combining them within coherent frameworks that prioritize consistency, explainability, and sustainability over methodological uniformity. Most national systems do not rely on a single method. Instead, they combine methods by property type, market segment, or data availability. Methodological diversity is therefore not a sign of weakness, but a response to heterogeneous markets.

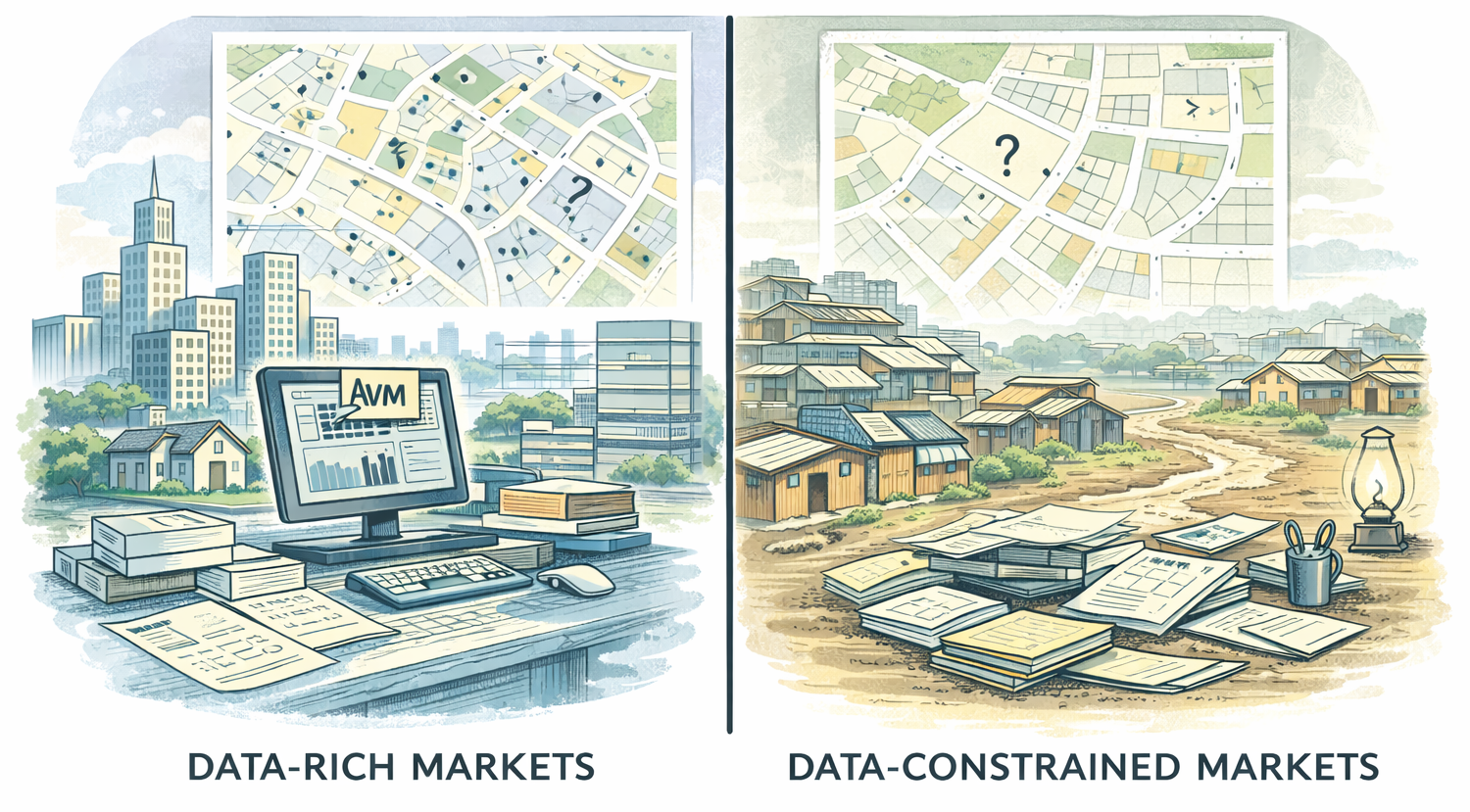

Classification by Data Environment and Market Maturity—Data conditions exert a powerful constraint on valuation design. Dense, transparent property markets with reliable transaction prices support statistical modeling and automation. Thin markets, informality, or fragmented records do not.

A third critical way to classify mass valuation systems is by the data environment and level of market maturity in which they operate. Data conditions shape not only which valuation methods are technically feasible, but also how stable, defensible, and scalable a system can be. While methodological choices often receive the most attention, experience shows that data environment is frequently the binding constraint in valuation design. Systems that are misaligned with data realities—by assuming dense markets, complete records, or seamless integration—tend to produce fragile results and face rapid loss of institutional and public confidence.

In data-rich and mature markets, valuation systems can rely on frequent, transparent transactions, consistent parcel definitions, and reliable building and ownership records. These conditions enable the use of statistical and automated methods, as models can be trained and validated against observed market behavior. Spatial accuracy allows values to respond to location with precision, and regular data updates support frequent revaluations. However, even in such environments, data governance remains essential; without clear standards, version control, and auditability, complexity can undermine trust rather than enhance it. Maturity therefore enables automation, but does not eliminate the need for oversight.

In contrast, data-constrained or immature markets are characterized by sparse or unreliable transaction data, informal development, inconsistent parcel boundaries, and fragmented institutional data ownership. In these contexts, attempting to deploy sales-based or highly automated valuation systems often leads to unstable outputs that cannot be explained or defended. Instead, valuation approaches must rely on proxies, standardization, and conservative assumptions. Rules-based systems, land value zoning, reference parcels, and hybrid methods are commonly used to compensate for data gaps while maintaining consistency. The constraint is not the absence of data per se, but the lack of reliable, comparable, and accessible data at scale.

Market maturity also affects how data can be integrated institutionally. In many countries, datasets relevant to valuation—such as cadastral maps, building records, transaction prices, and tax rolls—are held by different agencies with distinct mandates and legal constraints. Valuation authorities may depend on data they do not control, making access, update cycles, and quality assurance governance challenges rather than purely technical ones. Effective systems acknowledge this reality by designing workflows that accommodate partial integration, asynchronous updates, and negotiated data sharing, rather than assuming unified databases.

The practical implication is that successful mass valuation systems are designed to work with available data and improve it over time, not to wait for ideal conditions. Data environment and market maturity are therefore not static classifications, but evolving characteristics that inform sequencing decisions. Systems that align valuation methods, automation levels, and governance arrangements with current data realities—and adapt as those realities improve—are far more likely to achieve durable, credible outcomes. Systems that ignore these realities often fail. Effective mass valuation systems are those designed to work with available data, not idealized datasets.

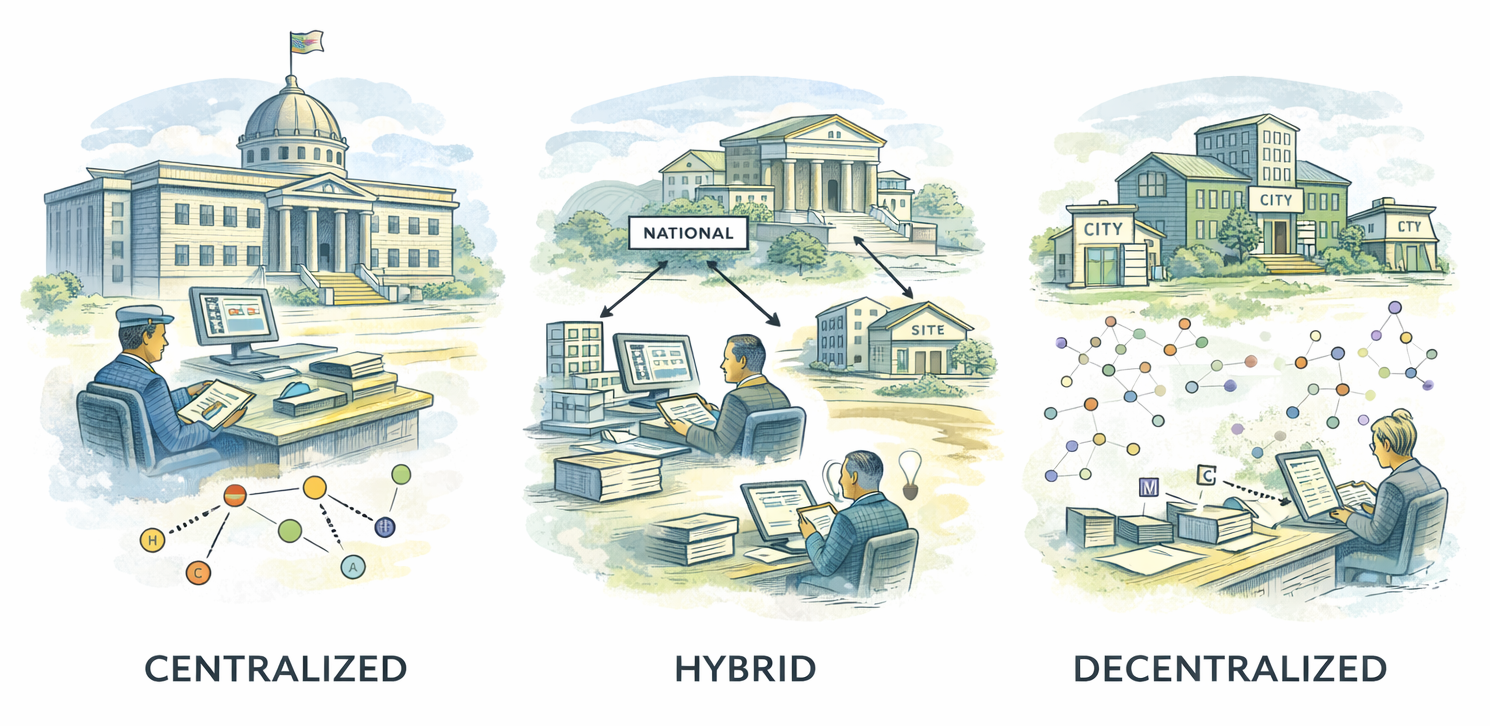

Classification by Governance and Institutional Design—Finally, governance matters. Who owns the valuation function? Who approves results? Who handles appeals? Is valuation centralized nationally, delegated to municipalities, or shared across agencies?

A final and often decisive way to classify mass valuation systems is by their governance and institutional design. Governance determines where authority over valuation resides, how decisions are made and approved, and how accountability is enforced. Unlike methodology or automation, which focus on how values are calculated, governance addresses how valuation functions as a public institution. It shapes legitimacy, legal defensibility, and long-term sustainability, and often determines whether technically sound systems succeed or fail in practice.

At one end of the spectrum are centralized valuation systems, where a national authority is responsible for standards, methods, and often the production of values. These systems benefit from consistency, economies of scale, and professional specialization, and are well suited to jurisdictions seeking uniformity across regions. However, centralization can distance valuation from local market knowledge and may slow responsiveness unless strong coordination mechanisms are in place. Their effectiveness depends on clear mandates, stable funding, and formalized relationships with local governments.

At the other end are decentralized systems, in which valuation responsibilities are delegated to municipalities or local authorities. These systems can leverage local expertise and adapt to market nuances, but they often face challenges related to uneven capacity, inconsistent practices, and difficulties maintaining national equity. Without strong frameworks for standards, oversight, and data sharing, decentralization can undermine comparability and public confidence, even when local execution is technically competent.

Between these extremes lie hybrid governance models, which are increasingly common in practice. In such systems, central authorities define standards, provide tools, and oversee quality assurance, while local entities apply methods, collect data, and manage taxpayer interaction. Hybrid models aim to balance consistency with local relevance, but they require careful design to avoid blurred accountability or duplication of effort. Clear role definition, documented workflows, and effective coordination are essential to their success.

Across all governance models, appeals and transparency mechanisms are integral components rather than auxiliary features. Systems that lack credible appeal pathways or that obscure decision-making logic risk rapid erosion of trust, regardless of analytical quality. Conversely, well-governed systems embed valuation within legal and administrative processes that allow scrutiny, correction, and learning over time.

Taken together, governance and institutional design provide the connective tissue that links data, methods, and automation into a functioning system. With these classification lenses in place—automation, methodology, data environment, and governance—the discussion can now turn to the main mass valuation system types observed in global practice and how these classifications combine in real-world implementations. With these classification lenses in mind, the sections below describe the main system types observed in practice.

Manual and Expert-Led Mass Valuation Systems

What Defines a Manual Mass Valuation System: Manual mass valuation systems generate values for large numbers of properties using expert-defined rules and standardized procedures, with minimal automation. Values are often calculated using spreadsheets, paper records, or basic databases, but the logic remains largely human-driven.

Assessors apply predefined criteria consistently across properties, allowing the system to function at scale despite limited technological infrastructure. These systems are best understood not as individualized appraisals repeated many times, but as structured mass processes grounded in professional judgment.

The defining strength of manual systems lies in their predictability and transparency. By applying the same schedules, zones, or scoring rules across wide areas, assessors can ensure uniform treatment even in the absence of detailed or reliable market evidence. This makes manual systems particularly suitable for environments where transaction data is sparse, records are fragmented, or legal frameworks emphasize explainability over market responsiveness. While labor-intensive, well-managed manual systems can produce stable and defensible valuation outcomes, especially when institutional knowledge is strong and turnover is limited.

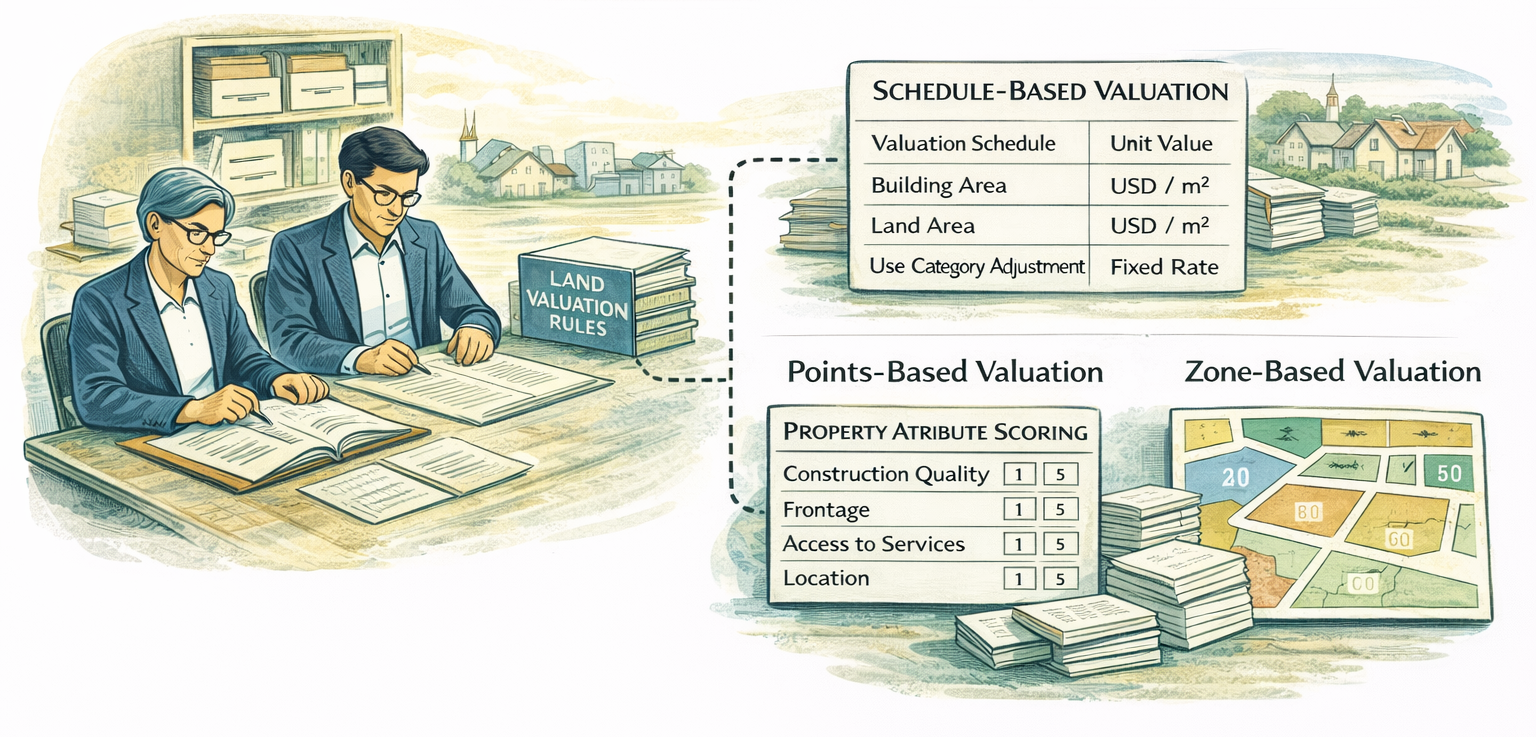

One common form of manual mass valuation is schedule-based valuation, in which predefined tables assign values according to factors such as land area, building size, use category, or location. These schedules are typically developed through expert analysis and periodic review, rather than continuous market observation. Schedule-based systems are straightforward to administer and easy to explain to taxpayers, but they are constrained by their rigidity. Without regular updates, schedules can lag behind market conditions, and their accuracy depends heavily on the quality of the initial assumptions.

Another widely used approach is the points-based or scoring system, where properties are evaluated against a set of attributes—such as construction quality, access to services, frontage, or neighborhood characteristics—and assigned a cumulative score that corresponds to a value band. This method allows assessors to incorporate qualitative differences between properties in a structured way, even when price data is unavailable. Points-based systems are enabled by clear attribute definitions and assessor training, but they can become subjective if scoring criteria are poorly specified or inconsistently applied.

A third variant is zone-based land valuation, where land values are defined for geographic zones and adjusted manually to reflect factors such as accessibility, infrastructure, or permitted use. This approach is particularly effective where land location is the primary driver of value and building data is incomplete or unreliable. Zone-based systems can be scaled across large areas with limited data requirements, but they depend on coherent zoning logic and can oversimplify value gradients in complex urban environments.

Manual mass valuation systems are often the starting point for valuation reform, especially in low-income, post-conflict, or rapidly reforming contexts where digital infrastructure and data integration are still emerging. They remain prevalent in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and fragile states, and are also used selectively in higher-income countries for property categories where market evidence is weak or irregular. Their continued use reflects not technological backwardness, but a pragmatic alignment between institutional capacity, data reality, and legal expectations.

Where This Approach Is Used: These approaches allow assessors to produce mass valuations without statistical modeling, relying instead on standardized expert logic. Manual mass valuation systems remain prevalent in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and post-conflict states where land markets are thin and institutional capacity is evolving. They are also used in some European contexts for specific property categories where market evidence is weak.

Rules-Based and Schedule-Based Mass Valuation Systems

Core Logic of Rules-Based Valuation: Rules-based systems formalize valuation logic explicitly. Rather than relying on assessor discretion, they encode rules—such as unit values, adjustment factors, or depreciation curves—that are applied consistently across properties.

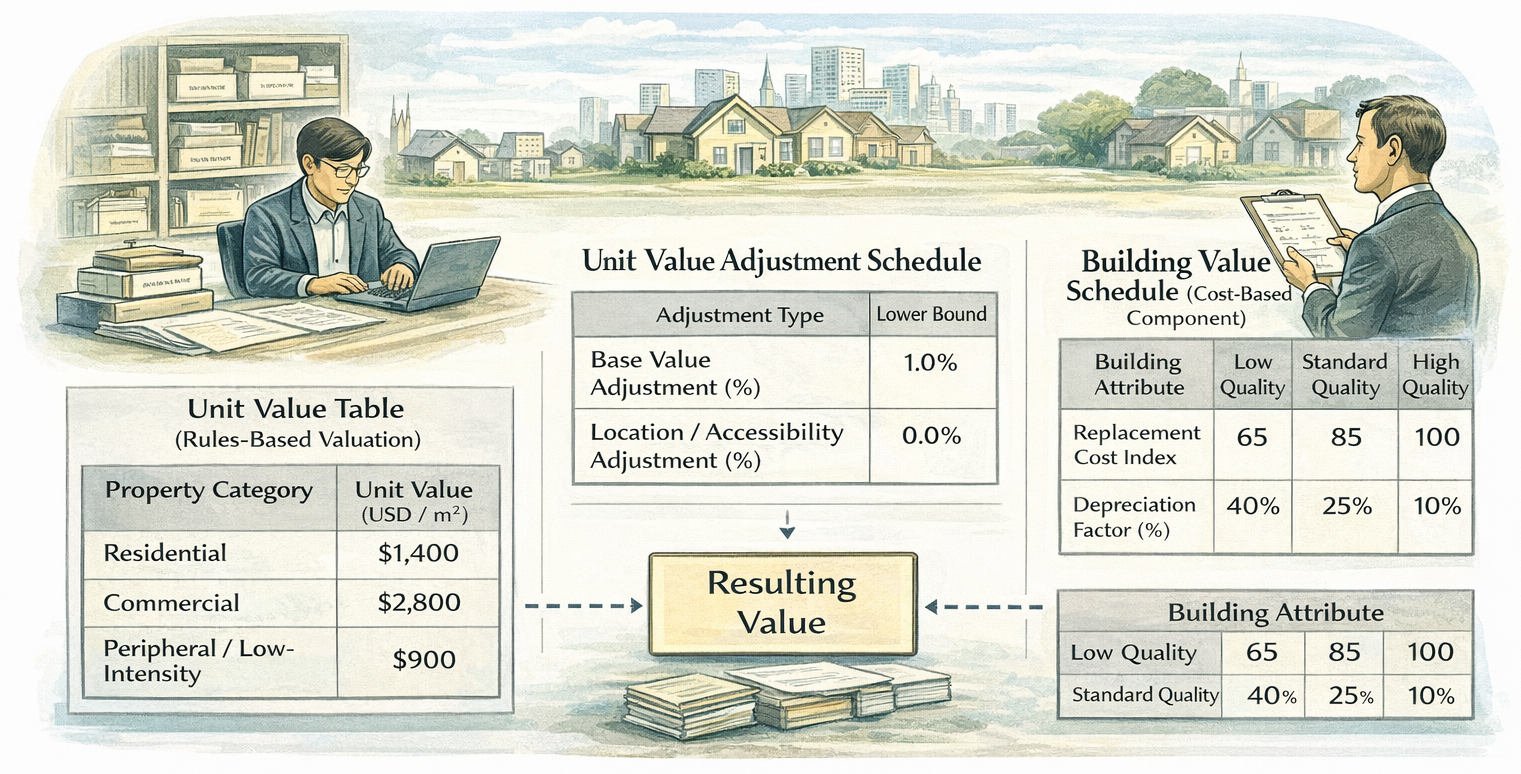

Rules-based mass valuation systems encode explicit rules that are applied uniformly across properties. Unlike purely manual systems, where judgment plays a central role at the point of valuation, rules-based systems separate rule-setting from rule application. Values are generated by applying predefined parameters—such as unit rates, adjustment coefficients, or depreciation schedules—through consistent procedures, whether executed manually or supported by basic software.

The primary strength of rules-based systems lies in their clarity and explainability. Every valuation outcome can be traced back to a defined set of rules that are documented, reviewable, and repeatable. This makes such systems particularly attractive in legal and administrative environments where valuation outcomes must be defended publicly or adjudicated through formal appeal processes. While rules-based systems are typically less responsive to short-term market fluctuations than sales-based models, they offer predictability, institutional control, and ease of administration—qualities that are often more important than precision in public sector valuation.

One common form of rules-based valuation is the unit value system, where properties are assigned values based on standardized rates per square meter of land or built area, differentiated by use, zone, or category. Unit value systems are straightforward to implement and scale, making them suitable where data on property attributes is available but transaction evidence is limited. Their effectiveness depends on the credibility of the underlying rate structure and the frequency with which rates are reviewed and updated. Without periodic recalibration, unit values can drift away from economic reality.

A related approach is land value zoning, which assigns base land values to defined geographic zones and applies structured adjustments to account for factors such as frontage, accessibility, infrastructure, or permitted use. Land value zoning is particularly effective where location is the dominant driver of value and where building data is incomplete or inconsistent. By anchoring valuation in spatial logic, zoning systems can operate with relatively modest data requirements. However, they require careful zone delineation and transparent adjustment logic to avoid oversimplification or perceived inequity.

Rules-based systems are also commonly implemented through cost-based schedules, which estimate property value by combining standardized construction costs with depreciation curves and land value components. These systems are especially useful for property types that trade infrequently or where market prices are unreliable, such as public buildings or specialized assets. Their success depends on realistic cost benchmarks and depreciation assumptions that reflect actual asset performance rather than purely accounting conventions.

Where This Approach Is Used: In practice, rules-based valuation systems often form the backbone of mass valuation in data-constrained environments, serving either as long-term solutions or as transitional frameworks during digitization and data improvement. They are widely used in Latin America, parts of Asia, and transitional economies where legal defensibility, administrative capacity, and institutional transparency take precedence over market sensitivity. Their persistence reflects not a lack of sophistication, but a deliberate choice to prioritize governance and sustainability in challenging data contexts.

Semi-Automated CAMA Systems (Human-in-the-Loop)

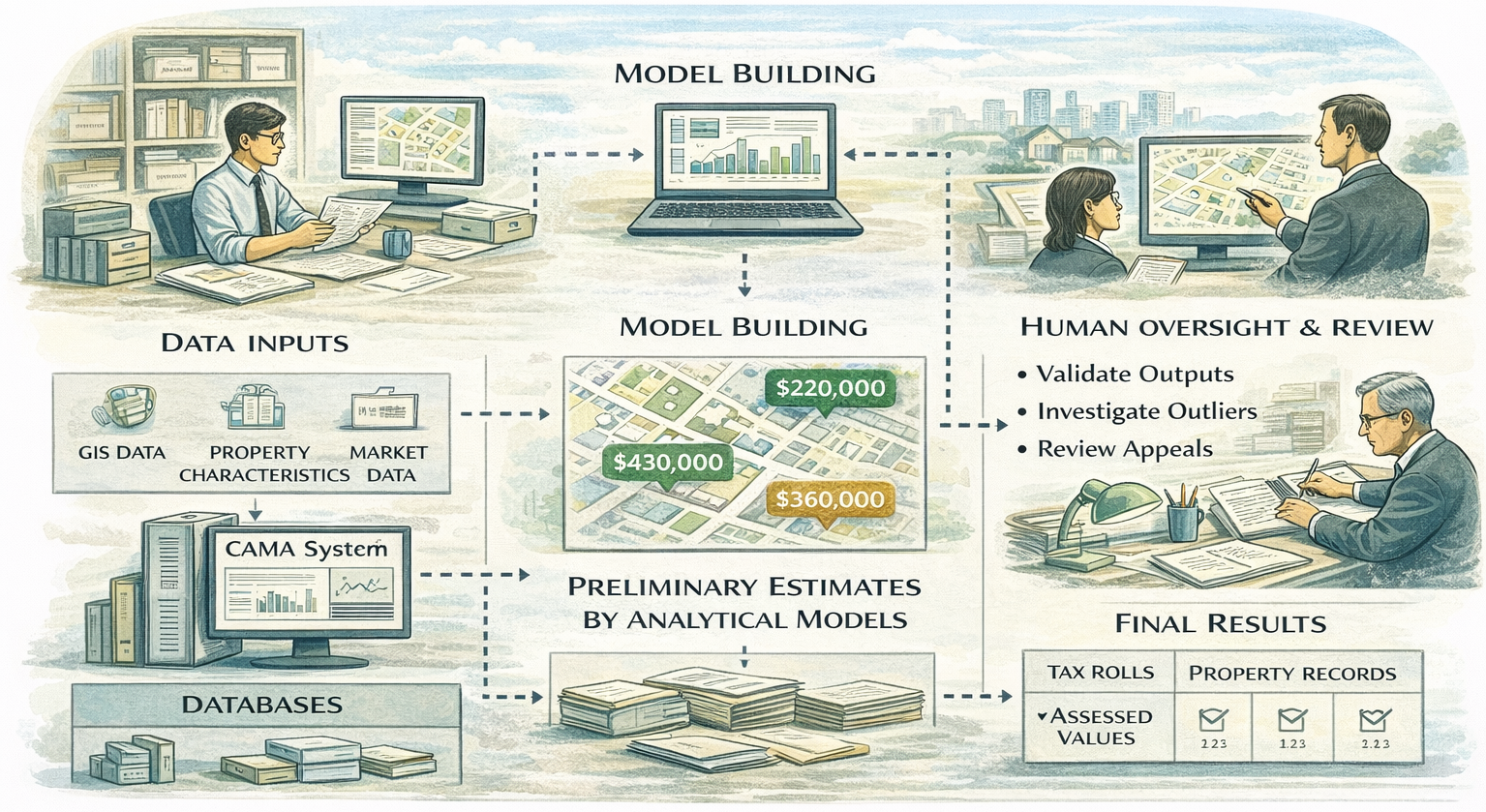

What “Semi-Automated” Really Means: Semi-automated CAMA (Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal) systems represent the most common form of modern mass valuation. They combine databases, GIS, and analytical models with structured human oversight.

As the most prevalent and practically durable form of modern mass valuation, they combine structured databases, geographic information systems, and analytical models with explicit human oversight embedded into the valuation workflow. Rather than attempting to eliminate professional judgment, semi-automated systems formalize where and how judgment is applied, ensuring that automation enhances efficiency without displacing institutional accountability.

In these systems, analytical models generate baseline or preliminary values across large property sets, drawing on available spatial, legal, and market data. Human assessors then review outputs, investigate anomalies, validate assumptions, and manage exceptions and appeals. Automation accelerates repetitive processing and improves consistency, while human involvement preserves legitimacy, interpretability, and legal defensibility. This balance is not accidental; it reflects an understanding that valuation outcomes must be explainable and contestable within administrative and judicial processes.

Semi-automated CAMA systems can take several forms depending on data availability, market structure, and institutional capacity. In regression-based CAMA, statistical models are used to estimate the contribution of property attributes to value, typically in data-rich segments such as urban residential markets. These systems are enabled by reliable transaction data and consistent property characteristics, but require ongoing monitoring to manage model drift and market volatility.

Other systems adopt a hybrid CAMA approach, combining sales-based models with cost schedules, land value zoning, or rules-based adjustments. Hybrid designs are particularly effective in heterogeneous environments, where some property segments support statistical modeling while others do not. By integrating multiple valuation logics within a single system, hybrid CAMAs reduce the risk of forcing unsuitable methods onto weak data while maintaining overall coherence.

A further variation is segmented CAMA, in which different valuation methods are applied explicitly to different property types or market segments. Residential, commercial, industrial, and special-use properties may each be valued using distinct approaches within the same administrative framework. Segmentation allows systems to respect market realities and institutional constraints, but it requires clear classification rules and strong coordination to avoid inconsistency.

In data-constrained contexts, semi-automated systems may rely on reference-parcel or exemplar-based approaches, where a limited number of representative properties are valued in detail and used as anchors to propagate values across similar parcels. This approach reduces data demands while retaining analytical structure, but depends on careful selection of reference parcels and transparent adjustment logic.

Where This Approach Is Used: Semi-automated CAMA systems are widely used across North America, Europe, and many middle-income countries, and they are the primary reform target for jurisdictions transitioning from manual or rules-based valuation. Their dominance reflects not technological conservatism, but institutional realism: they offer a scalable path toward modernization while preserving professional oversight, public trust, and legal defensibility. In most contexts, semi-automation is not a transitional compromise, but a stable and intentional end state.

Fully Automated and AVM-Driven Mass Valuation Systems

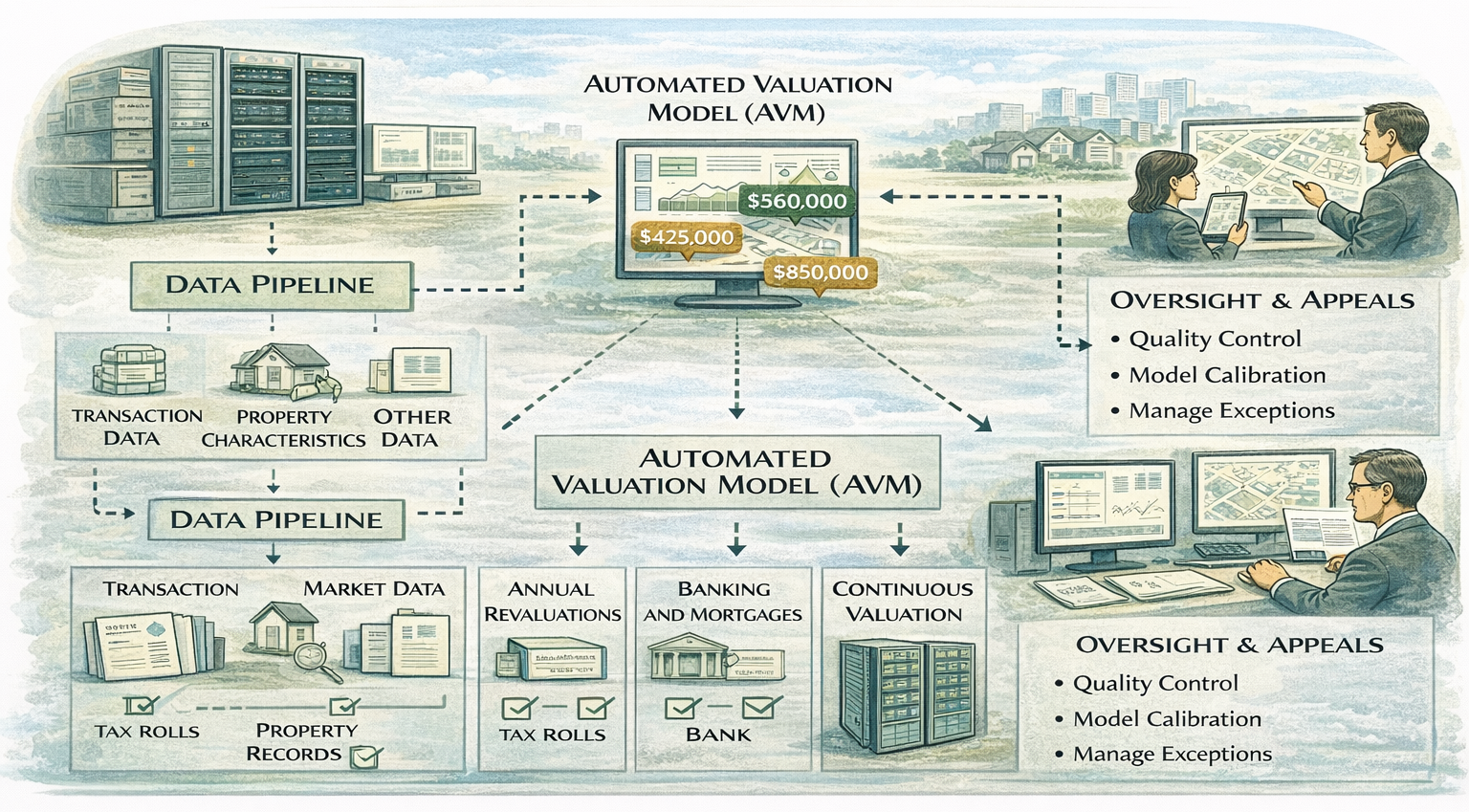

From CAMA to AVM-Centric Systems: Fully automated systems push automation further by relying on Automated Valuation Models (AVMs) to generate values with minimal human intervention. These systems often update values annually or continuously.

Fully automated mass valuation systems represent the highest level of automation currently observed in practice, relying primarily on AVMs to generate property values with minimal routine human intervention. In these systems, valuation logic is embedded within model pipelines that ingest data, estimate values, and update outputs on a scheduled or continuous basis. Human involvement is largely shifted upstream, toward model governance, quality assurance, and exception oversight, rather than individual property review.

AVM-centric systems are most effective where market behavior can be observed reliably and at scale. They depend on dense and transparent transaction data, consistent property identifiers, accurate spatial representations, and regular data refresh cycles. Under these conditions, models can be trained, validated, and recalibrated with sufficient frequency to maintain alignment with market trends. Where these prerequisites are absent, however, automation can amplify errors and undermine institutional credibility, as model outputs may diverge from observable reality without obvious explanation.

One common form of full automation is the national AVM pipeline, in which valuation authorities apply standardized models across broad property segments to support periodic—often annual—revaluations. These systems emphasize consistency and timeliness, enabling governments to maintain up-to-date tax bases without extensive manual intervention. Their success depends not only on model performance, but also on strong legal frameworks that define how automated values are issued, reviewed, and appealed.

Another important category consists of mortgage-sector AVMs adapted for public valuation purposes. Originally developed for credit risk assessment and collateral estimation, these models are increasingly referenced or incorporated into public systems. While they offer sophisticated analytics and rapid updates, their underlying assumptions—such as market liquidity and transactional transparency—do not always align with public valuation objectives. Adapting finance-sector AVMs therefore requires careful recalibration, governance oversight, and transparency to ensure public defensibility.

A more advanced manifestation is the continuous valuation system, in which values are updated dynamically as new data becomes available. Rather than discrete revaluation cycles, these systems treat valuation as an ongoing process. Continuous valuation offers responsiveness and analytical elegance, but it also raises governance challenges related to stability, taxpayer understanding, and appeal timing. Without clear rules governing when and how updated values take effect; such systems can create confusion or perceived arbitrariness.

Where This Approach Is Used: Fully automated and AVM-driven systems are concentrated in high-income countries with mature property markets, including parts of Northern Europe and Australasia, as well as within private financial institutions globally. Their limited geographic spread reflects not technological exclusivity, but institutional and data realities. Where governance capacity, data quality, and public trust align, full automation can be effective. Where they do not, semi-automated or hybrid systems often provide more durable and legitimate outcomes. AVM-centric systems require quite dense transaction data, reliable property attributes, and strong governance frameworks. Without these, automation risks undermining credibility.

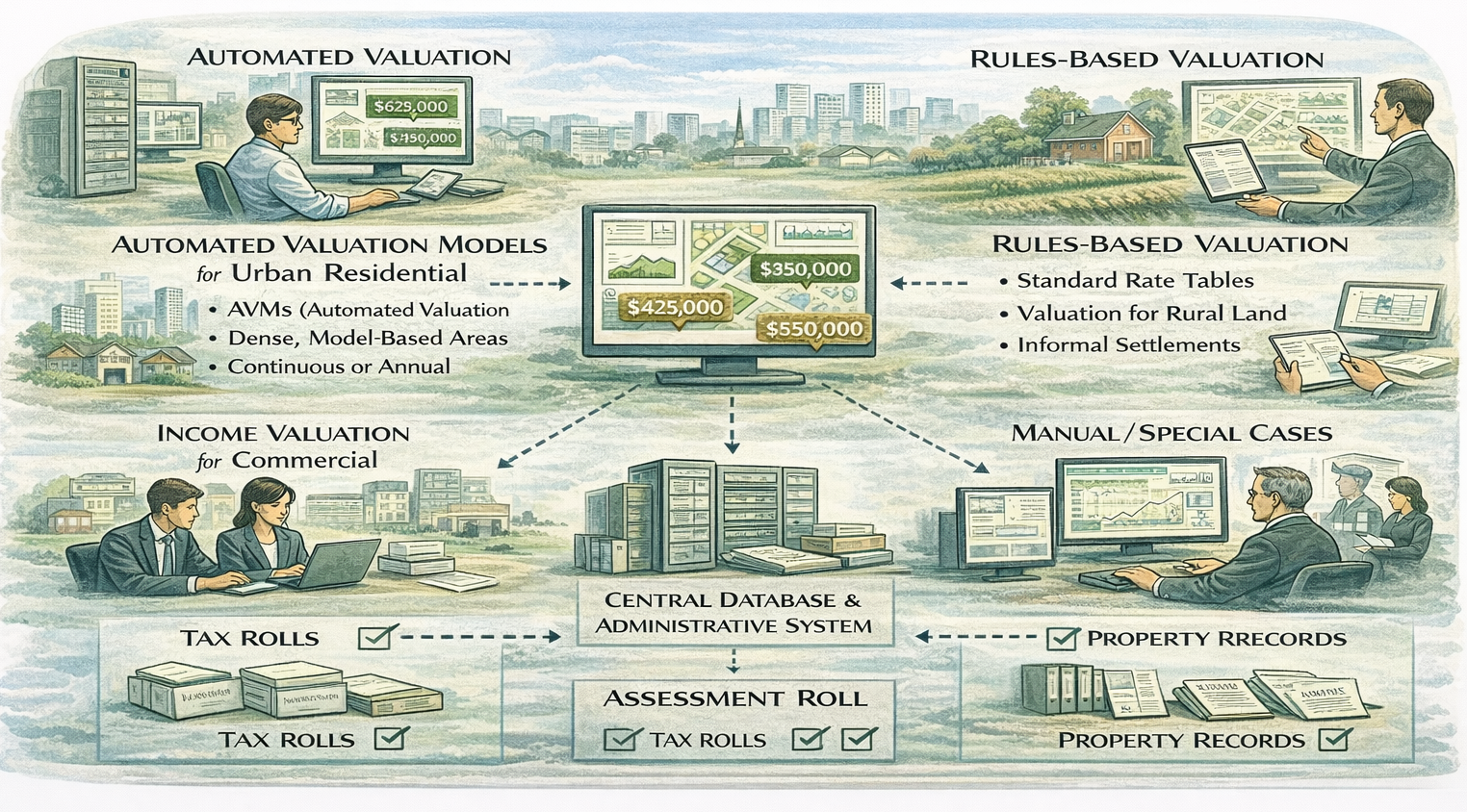

Hybrid and Tiered Mass Valuation Architectures

Why Hybrid Systems Are the Global Norm: Most countries operate heterogeneous property markets. Urban cores, informal settlements, rural land, and specialized properties cannot be valued effectively using a single method.

Hybrid and tiered mass valuation architectures have emerged as the dominant global pattern because most countries operate heterogeneous property markets that cannot be addressed effectively through a single valuation method or system design. Urban residential areas, informal settlements, rural land, commercial properties, and specialized assets differ fundamentally in data availability, market behavior, and institutional oversight. Hybrid systems acknowledge this diversity and respond by combining multiple valuation approaches within a single, coherent administrative framework.

The defining feature of a hybrid system is not methodological inconsistency, but explicit segmentation. Different valuation engines are applied deliberately to different property categories or market segments, based on where each method performs best. In dense urban residential markets, automated or semi-automated models may be used to capture market dynamics. In rural or informal areas, rules-based or land-focused approaches often provide greater stability and defensibility. Income-based models are typically reserved for commercial or rental properties where cash flow data is meaningful, while manual review or overrides are applied to special cases that fall outside standard classifications.

Tiered architectures also allow asynchronous evolution across the system. Some segments may advance toward greater automation as data quality improves, while others remain rules-based or manually supervised for extended periods. This flexibility enables gradual reform without forcing uniform advancement across all markets, reducing both technical and political risk. Importantly, hybrid systems can accommodate pilot initiatives, phased scaling, and targeted modernization without disrupting overall coverage or equity.

The effectiveness of hybrid architectures depends heavily on clear segmentation rules, consistent governance, and strong coordination mechanisms. Without explicit criteria defining which properties are valued under which approach, hybrid systems risk appearing arbitrary or opaque. Successful implementations therefore invest in classification frameworks, documentation, and communication to ensure that methodological differences are understood as deliberate and justified.

Hybrid and tiered mass valuation architectures are increasingly used in large and diverse countries, where market conditions, institutional capacity, and data maturity vary widely across regions and property types. Their prevalence reflects institutional realism rather than technical limitation. By aligning valuation methods with market reality and governance capacity, hybrid systems provide a durable pathway for modernization while preserving legitimacy, coverage, and public trust.

In practice, hybrid mass valuation systems tend to converge around a small number of recurring configuration patterns. AVMs for urban residential property are most commonly used in dense markets where transaction data supports statistical estimation and regular updates. Rules-based methods for rural or informal areas provide stability and explainability where sales evidence is sparse or unreliable. Income models for commercial properties are applied where value is driven primarily by rental flows rather than physical characteristics. Across all segments, manual overrides for special cases remain an essential safeguard for atypical properties, data anomalies, and legally sensitive situations. These configurations are not accidental; they reflect accumulated practice about which valuation approaches are defensible, sustainable, and institutionally manageable in different market contexts.

Where This Approach Is Used: Large and diverse countries increasingly rely on hybrid valuation architectures to manage uneven data quality, market maturity, and institutional capacity across regions. Variants of this approach can be observed in countries such as the United States, Canada, Brazil, India, and South Africa, where urban residential markets support model-based valuation while rural, informal, or specialized property segments continue to rely on rules-based or manually supervised methods within a unified administrative system.

Key Takeaways from Global Practice

Global practice demonstrates that mass valuation systems are not defined by technology, models, or software choices alone. They are institutional systems, shaped by how automation, valuation methodology, data environment, and governance design are combined in response to real-world constraints. Countries that succeed do so not by adopting a single “best” system, but by selecting and sequencing system components that align with their market structure, data maturity, legal frameworks, and administrative capacity.

Across contexts, effective systems exhibit three consistent characteristics: they embrace methodological plurality rather than uniformity, they evolve incrementally rather than through one-off technological leaps, and they treat valuation as a recurring public function rather than a technical project. Hybrid and tiered architectures are therefore not transitional anomalies, but the prevailing global norm, reflecting institutional realism rather than analytical compromise.

Understanding these system types and classification lenses is a prerequisite for meaningful reform, but it is not sufficient on its own. The critical question is not what types of systems exist, but how they are governed, implemented, and evolved over time. The next article turns from classification to practice, examining how data realities, institutional design, sequencing, and trust determine whether mass valuation systems actually work in sustained, real-world settings.

Part 2 focuses on implementation, governance, and reform pathways; it examines how mass valuation systems operate once they leave the diagram and enter real institutions, with real data constraints, legal requirements, and political pressures.

OHK has designed and implemented land and property valuation systems across multiple regions worldwide, with particular depth of experience in developing and transition economies. Our work spans mass valuation frameworks, cadastral integration, and institutional reform, supporting governments in strengthening fiscal systems, improving transparency, and enabling equitable land and property taxation. We combine management consulting, spatial planning, and international development into a unified, multidisciplinary practice. This ethos anchors our technical work, ensuring that valuation systems are not only technically sound, but also operationally viable, institutionally embedded, and aligned with international standards. Across diverse political and economic contexts, we help public institutions navigate complexity, modernize valuation practices, and deliver long-term public value grounded in accountability, transparency, and social impact. Contact OHK to explore how our valuation and planning capabilities strengthen data-driven decision-making across cities and urban systems.