What Egypt Might Have Been Without Nationalization: A Counterfactual Economic Exploration

Exploring the long-term economic cost of Egypt’s nationalization era, using real data, economic modeling, and global comparisons to examine a path not taken.

OHK was retained by a U.S.-based developer exploring entry into the Egyptian market. While the client saw strong potential in Egypt’s demographics, location, and recent economic reforms, they also voiced concern about the underlying structure of the economy. Their questions centered on the persistent dominance of the state, the expanding commercial role of the military, and regulatory constraints faced by private sector actors. During a strategy workshop, a junior analyst from the client’s team raised an unexpected question: “What would Egypt’s economy look like today if it had never been nationalized?” It was an offhand comment, yet it immediately shifted the conversation. What began as a historical curiosity turned into a serious analytical exercise, one that would come to inform market-entry deliberations far more deeply than anticipated. This article is the result of that inquiry. It seeks not to judge or politicize, but to analyze — grounding a counterfactual scenario in real economic data, comparative growth trajectories, and plausible assumptions. It does not deny the social gains or strategic imperatives of Egypt’s nationalization policies, nor does it dismiss the complex post-colonial pressures under which they were enacted. Rather, it serves as a reflective exercise — a way to understand how historical policy decisions echo across decades and shape present realities. By examining what was potentially lost in terms of GDP growth, foreign direct investment, entrepreneurship, and human capital, this article also encourages us to consider what might still be possible. It is as much about the future as it is about the past.

This article is important because Egypt today faces a reform paradox: meaningful liberalization efforts (e.g., PPPs, IMF-backed programs) coexist with persistent structural constraints. This piece explains why—not just by diagnosing the present, but by revisiting the institutional DNA that shaped it. That makes it useful not just to investors, but to policymakers, advisors, and anyone working on structural reform or private sector development in Egypt or similar post-state-dominant economies. This article integrates select artworks to visually and emotionally anchor its economic analysis, not as decoration but as narrative tools that humanize data and reflect the lived realities behind policy choices. Each piece was carefully chosen to represent a distinct phase or implication of Egypt’s post-nationalization journey. These works serve as cultural and psychological touchstones that complement the article’s counterfactual inquiry. All visual works remain the intellectual property of their respective artists, estates, or representing galleries, and are referenced here under fair use for critical commentary and illustration. No commercial reproduction is intended or implied.

Reading Time: 30 min.

Egypt’s Mid-Century Crossroads: Nationalism, Sovereignty, and Structural Economic Realignment

In the wake of the 1952 revolution, Egypt was at a strategic and ideological crossroads. The colonial legacy had left behind deep inequality, limited industrial base, and foreign control of much of the economy — especially in finance, insurance, shipping, and large-scale agriculture. Against this backdrop, Nasser’s regime embarked on a bold vision: to build national sovereignty through economic independence. Nationalization began in earnest with the Suez Canal in 1956 and rapidly expanded to cover banks, factories, transport, and utilities. By the early 1960s, over 80% of economic investment in Egypt came from the state. This shift was not just ideological — it was practical. Nasser’s government sought to dismantle elite dominance and redistribute opportunity through a centrally planned economic model inspired by Soviet developmentalism. This approach yielded some early gains: industrial growth rose in the short term, educational infrastructure expanded, and Egypt achieved some degree of macroeconomic stability. However, it also introduced systemic inefficiencies, entrenched bureaucracy, and disincentives for innovation. Importantly, it crowded out private sector participation and precipitated the exit of large expatriate business communities (Greeks, Italians, Jews, Armenians) who had been integral to Egypt’s commercial ecosystem.

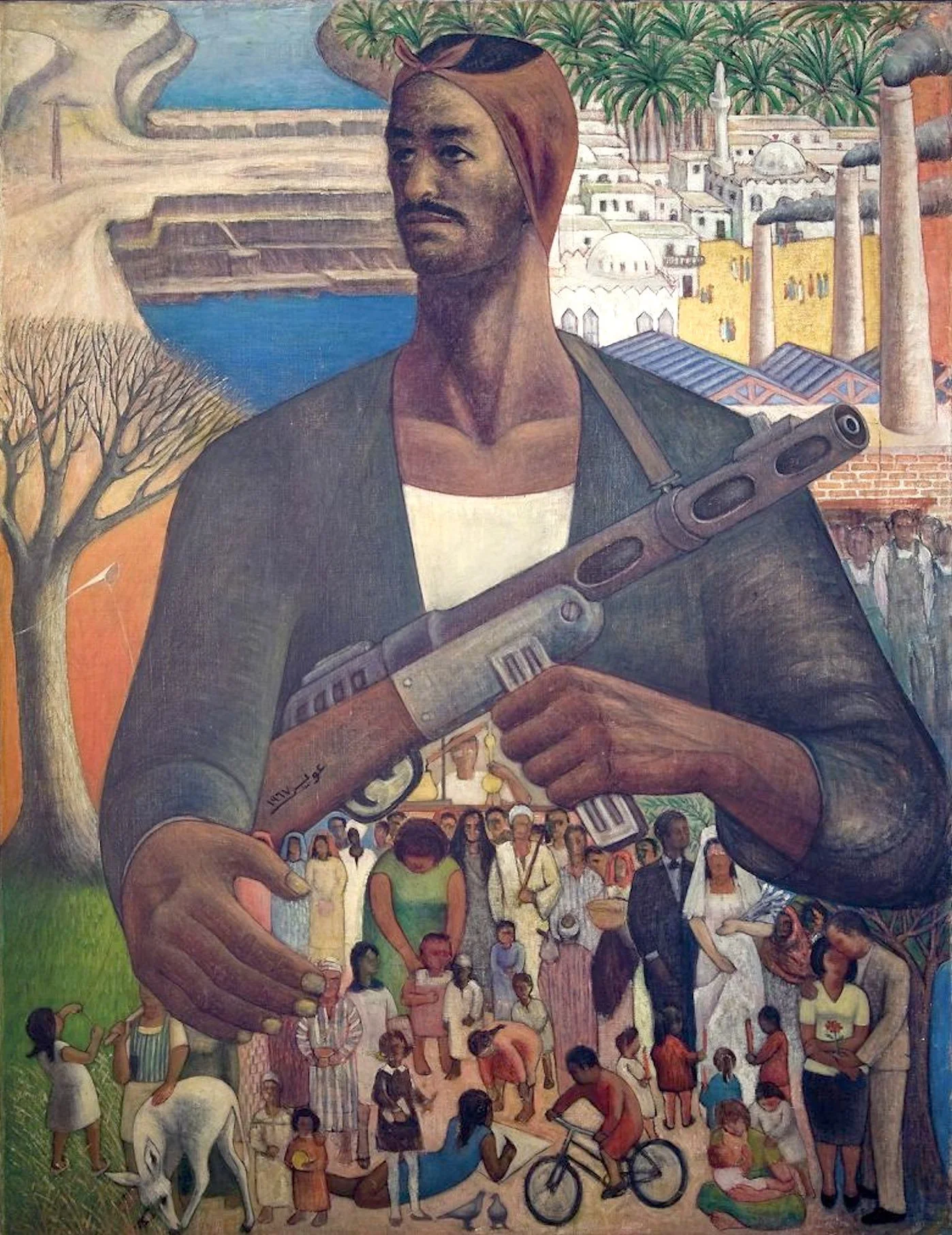

Hamed Ewais’s The Hero (1953) is a commanding allegory of the post-1952 revolutionary ethos. The central figure, an armed worker-soldier, towers protectively over a richly detailed panorama of Egypt — canals, farmland, mosques, smokestacks, and most critically, people. The bottom half teems with human life: children, farmers, students, newlyweds, and laborers — the very classes nationalization aimed to uplift. The weapon and the outstretched hand together evoke vigilance and solidarity, fusing national defense with social responsibility. This painting distills the revolutionary promise: a state-led reordering of society, rooted in egalitarianism, self-reliance, and unity. It perfectly anchors this section’s themes of sovereignty and economic transformation.

At the time of the 1952 revolution, Egypt’s population stood at approximately 21 million, with nearly 70% living in rural areas and dependent on agriculture. The economy was heavily dualistic: a largely subsistence agrarian base coexisted with pockets of advanced industry and finance, much of it controlled by foreign and minority elite communities. Egypt’s GDP in 1952 is estimated at around $5–6 billion (current USD), with per capita income hovering near $280, placing the country in the lower-middle income bracket globally. By 1956, the year of the Suez Canal nationalization, Egypt’s export earnings were dominated by cotton, which made up over 50% of foreign exchange income — a vulnerability that nationalists aimed to correct through industrial diversification. In line with this vision, the share of government-led investment surged from roughly 24% of gross fixed capital formation in 1952 to more than 80% by the early 1960s, as state entities took over finance, telecommunications, shipping, and heavy industries like cement and steel. The number of public sector enterprises rose from under 200 to over 1,000 in less than a decade. Meanwhile, the foreign commercial population — including an estimated 70,000 Greeks, 40,000 Italians, and 60,000 Jews — began to decline precipitously, with the combined foreign business community shrinking by more than 60% between 1956 and 1967. On the social front, Egypt expanded primary school enrollment from 2.2 million in 1952 to 5 million by 1970, and illiteracy among youth began to decline. Yet, productivity gains lagged: while industrial output grew at 6–7% annually in the early 1960s, total factor productivity remained flat or negative. These metrics reflect a mixed legacy — impressive mobilization and equity gains, but at the cost of efficiency, private sector dynamism, and long-term competitiveness.

Measuring the Cost of Lost Growth: Modeling GDP Under an Alternative Economic Path

To estimate the economic impact of nationalization, OHK employed compound growth modeling and comparative benchmarking with peer economies that followed more liberalized economic paths — including Turkey, Malaysia, and South Korea. Egypt’s real GDP per capita grew at approximately 2.5–3% per year from the late 1950s through the 1970s. In contrast, Malaysia and South Korea — countries with comparable post-colonial challenges — averaged 5–7% growth over similar periods. Modeling Egypt’s 1965 GDP of approximately $20 billion forward under a 5.5–7% growth rate, we find that its 2025 GDP could have reached $1.1 to $1.2 trillion rather than the $400–500 billion it currently projects. This counterfactual model assumes no exogenous shocks (wars, embargoes, revolutions) but does build in modest productivity and capital investment improvements. It does not presume a flawless market economy — only one where private enterprise, competition, and foreign investment played a more prominent role. The result? Egypt’s economy today might be two to three times its current size. Per capita income could have approached middle- to high-income levels. More importantly, Egypt would likely have had more resilient institutions and a diversified private sector able to withstand shocks and create scalable innovation.

“Al Ashjar Tamout Wakifa” (The Trees Die Standing Up) by Hussein Bicar (1995) poignantly reflects Egypt’s economic journey — a nation that stood tall through hardship, yet bore the weight of missed opportunity. The Egyptians in the painting, laboring with dignity among lifeless trees, echo the resilience of Egyptians under a rigid system that limited growth. Just as the barren landscape suggests what could have bloomed, Egypt’s economy might have flourished under a more open model. The painting becomes a quiet testament to perseverance — and a reminder of the unseen cost of unrealized potential.

To support this analysis, OHK modeled Egypt’s economic trajectory starting from an estimated GDP of $20 billion in 1965 (in nominal USD), when the country’s population was around 30 million, and per capita income stood at approximately $667. From 1965 to the late 1970s, Egypt’s real GDP per capita growth hovered between 2.5% and 3% annually, restrained by low productivity growth, rigid planning mechanisms, and minimal foreign direct investment. In contrast, South Korea, starting from a similar GDP per capita in the early 1960s (~$600), achieved annual GDP per capita growth rates of 6–8% for over three decades, reaching over $35,000 by 2020. Malaysia, with a smaller population but a parallel colonial history and export-dependent economy, grew its per capita income from $800 in 1965 to over $11,000 by the mid-2010s. Assuming Egypt had achieved average annual growth of 5.5–7%, its 2025 GDP, as mentioned earlier, could plausibly fall between $1.1 and $1.2 trillion. That would represent a tripling of total economic output and potentially lift per capita income from the current $3,800–$4,000 range to over $10,000, placing Egypt firmly in the upper-middle-income bracket alongside countries like Mexico or Turkey. These gains wouldn’t have come from GDP alone. Sustained higher growth would likely have produced more diversified exports, greater labor force participation, higher education attainment, and greater FDI stock. Today, Egypt’s FDI inflows remain around 2% of GDP, whereas Malaysia’s peak years saw over 6%. The model also assumes moderate improvements in total factor productivity, which in Egypt’s case has lagged behind peers due to capital misallocation and low innovation absorption. The counterfactual is conservative — and yet striking in its implications.

The Flight of Talent, Capital, and Entrepreneurship: How Egypt’s Commercial Class Disappeared

One of the most visible impacts of nationalization was the mass departure of foreign and minority Egyptian business communities. Tens of thousands of Greeks, Armenians, Jews, Italians, and Levantines left Egypt between 1956 and 1967. Many were industrialists, bankers, and skilled professionals. This exodus represented a substantial loss of human capital and entrepreneurial energy. These communities had operated Egypt’s shipping fleets, cotton export networks, cinema production, and retail chains. Their businesses were often vertically integrated and internationally connected. The vacuum left behind was not filled by a new class of entrepreneurs, but by state agencies with limited commercial incentives. The result was a dramatic slowdown in innovation, exports, and service sector development. Egypt lost not just capital — it lost know-how, relationships, and institutional continuity. Had these communities remained and continued to invest, Egypt may have evolved a stronger SME ecosystem, diversified exports, and more robust private finance networks. Instead, talent flight reinforced dependency on state-led initiatives, which increasingly struggled under global headwinds.

This image, titled You Never Left # I (2010) by Youssef Nabil, is part of his Exile series. While not a painting, the hand-colored photograph conveys the quiet solitude and emotional rupture of departure. Depicting a lone man pushing a luggage cart through a vast desert, it evokes the mass exodus of Egypt’s commercial and minority communities following nationalization in the 1950s and 60s. Nabil’s work speaks to the enduring pain of migration — a physical and emotional displacement. Here, the stark emptiness of the landscape mirrors the vacuum left behind when capital, talent, and entrepreneurial energy fled Egypt.

Between 1956 and 1967, Egypt experienced a significant demographic and commercial upheaval. An estimated 150,000 to 160,000 individuals from key expatriate and minority Egyptian business communities departed the country during this period. These groups, though collectively accounting for less than 3% of Egypt’s population, represented a disproportionate share of the country’s entrepreneurial, financial, and technical expertise. They were deeply embedded in Egypt’s economy — managing major shipping lines, overseeing the cotton export trade, operating urban department stores, producing films, and running integrated textile and manufacturing facilities. For example, in Alexandria alone, more than 50% of cotton export firms were managed by Greek families. Jewish and Armenian entrepreneurs played leading roles in Egypt’s early banking and insurance sectors. These communities also acted as critical bridges to international capital and supply chains, thanks to their multilingual skills and transnational family networks. Their sudden departure — triggered by nationalization decrees, asset confiscation, and an atmosphere of political uncertainty — left a vacuum in Egypt’s commercial infrastructure. Rather than being filled by a new class of Egyptian entrepreneurs, the space was largely absorbed by state agencies that lacked incentives for innovation or efficiency. By the 1970s, the private sector’s share of GDP had fallen below 25%, and non-oil exports plateaued. Service sectors such as finance, retail, and logistics became highly centralized and underperforming. In contrast, countries like Turkey retained their merchant classes saw steady SME growth and export diversification. The human capital loss Egypt suffered during this period was not just numerical — it represented a rupture in institutional knowledge, commercial networks, and the continuity of a competitive private economy that may have otherwise flourished.

Financial Repression and Structural Inefficiency: The Hidden Drag on Productivity and Investment—Egypt’s Centralized Economic Machine and the Invisible Costs of Misallocated Capital, Overemployment, and Credit Repression

Beyond talent flight and capital loss, the nationalized economic model produced long-term structural inefficiencies. The financial system was state-run, credit was politically allocated, interest rates were suppressed, and capital was often diverted into low-yielding industrial projects. Without competitive pressure or innovation incentives, productivity stagnated. Labor absorption remained high but output per worker did not keep pace with global averages. State-owned enterprises dominated but were rarely profitable or globally competitive. Economic distortions included: Low capital efficiency—investments often went to prestige projects rather than scalable industries, subsidy dependency—consumer subsidies absorbed fiscal space, crowding out investment, and price controls: disincentivized supply responses and led to shortages. When combined, these factors likely shaved 1–2% off Egypt’s potential annual GDP growth over multiple decades. Even modest reforms in the 1980s and 1990s could not fully unwind the institutional inertia created by decades of centralized planning.

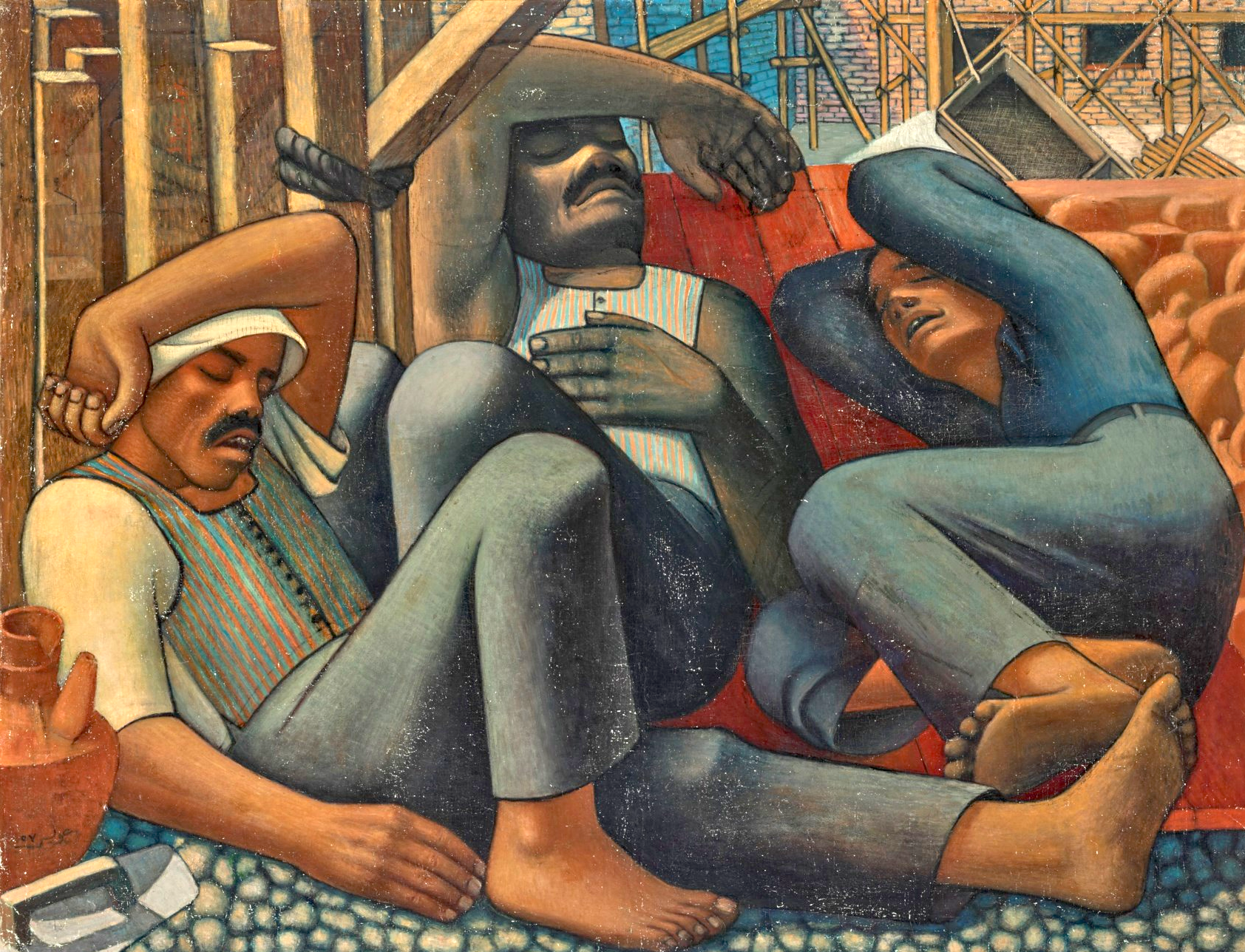

“Workers Resting” by Hamed Ewais (1975) quietly captures the promises and paradoxes of Egypt’s centralized economic experiment — a vision built on the back of labor, yet burdened by inefficiency. The image of exhausted workers lying among scaffolding and unfinished structures evokes both pride and fatigue. These men — symbols of a modernizing Egypt — embody the human cost of a system that prized full employment but undervalued productivity. Painted to honor the dignity of labor and Egypt’s working class, it reflects the physical toll of nation-building. Yet in hindsight, the image also reveals the weight of a system where labor was abundant but output lagged — where dreams of industrial transformation often gave way to bureaucratic inertia and misallocated resources.

By the mid-1960s, Egypt’s centrally planned economy had become among the most state-dominated outside the Eastern Bloc. Over 90% of large-scale industry and nearly all strategic infrastructure were under government control. The financial sector was nationalized in 1960, and by 1961, all major banks, insurance firms, and lending institutions were subsumed into the public sector. Credit allocation ceased to be governed by market dynamics and instead followed bureaucratic mandates, favoring politically aligned industries and prestige infrastructure projects. One of the more subtle consequences of this transition was the misallocation of capital across the economy. A 1978 IMF study comparing Egypt to its regional peers found that Egypt’s incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR) — a measure of investment efficiency — was nearly double that of Tunisia and Morocco, indicating that Egypt had to invest significantly more capital to generate the same level of economic output. Much of this capital went into industrial overcapacity, with factories running well below utilization rates. By the late 1970s, over 35% of installed industrial production capacity in state firms remained idle due to weak demand, poor logistics, or lack of complementary inputs.

Meanwhile, public sector overemployment became a hallmark of the system. Government enterprises and ministries absorbed labor not based on need but as a form of social stability. By 1982, the public sector employed 35% of the formal labor force, yet accounted for less than 20% of GDP contribution — a clear mismatch in productivity. Wage compression policies further discouraged skilled labor retention, pushing much of the technically trained workforce into informal or expatriate markets. The state also maintained artificially low interest rates, typically below inflation, which discouraged household savings and crowded out private credit. As late as 1985, less than 15% of bank loans were issued to the private sector, with most lending concentrated in public firms, many of which were non-performing. These structural inefficiencies may not have sparked immediate crises, but they cumulatively depressed Egypt’s growth potential by 1–2 percentage points annually. Crucially, they also created institutional norms — low accountability, politicized budgeting, and planning inertia — that would persist well beyond the formal era of Arab socialism.The key takeaway is that inflation indexing, currency context, and sensitivity testing are essential tools in evaluating the viability of megastructures. Pegged currencies like the AED or SAR create nominal clarity, but not immunity from real-cost escalation. Real-dollar adjustments expose whether a project generates true economic surplus beyond currency illusions. And when conservative stress cases—30% price corrections, 3–5 years of underperformance, extended vacancy—still yield near-break-even returns, the project crosses into resilience-grade investment territory.

Foreign Direct Investment and Global Integration: The Opportunity That Never Fully Materialized—Missed Investment Waves and the Long-Term Cost of FDI Absence in Egypt’s Key Growth Sectors

FDI is a key driver of technology transfer, job creation, and export competitiveness. Egypt’s inward FDI was consistently low throughout the 1960s–1980s, as nationalization discouraged foreign participation and raised fears of asset expropriation. While Egypt did receive bilateral aid and loans (especially from the USSR), this was not equivalent to open-market investment. The capital that entered the country often came with strings attached and was not aimed at long-term entrepreneurial growth. In contrast, peers like Malaysia aggressively courted FDI in manufacturing, electronics, and later services. The result was the creation of high-tech export clusters and millions of formal jobs. Had Egypt opened earlier to foreign capital, especially in sectors like textiles, tourism, and energy, it may have developed more diversified, competitive export sectors. Missed FDI opportunities represent not just financial loss — but a delayed integration into global value chains.

“At the Aswan Dam” by Hamed Ewais (1965) captures the monumental ambition of Egypt’s post-revolution industrial era — a nation quite literally reshaping its geography in pursuit of self-reliance and modernity. Painted during the dam’s construction, the work glorifies the heroic scale of labor and machinery, projecting a powerful image of sovereign development. Yet, while the dam itself symbolized national pride and strategic autonomy, it also represents the economic path Egypt chose — one built on bilateral alliances and state-led megaprojects rather than market-driven foreign investment. Funded by Soviet loans after the fallout with Western powers, the project epitomized a closed-door model that discouraged FDI and limited entrepreneurial spillovers. Unlike foreign direct investment, which brings in risk-bearing capital, competitive pressures, and global integration, the capital that built the dam came with political strings and flowed mainly into non-export, non-scalable sectors. Ewais’ painting, though celebratory, unwittingly illustrates the long-term costs of this model — immense physical transformation but limited private sector growth. In hindsight, it stands as both a tribute to national will and a quiet reminder of the global opportunity that eluded Egypt during a pivotal economic era.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) serves as a powerful engine of productivity growth, industrial diversification, and export integration. From the 1960s through the late 1980s, Egypt largely missed this global wave. Despite its geographic advantages and market size, Egypt’s average annual FDI inflow between 1970 and 1990 was just 0.5–0.9% of GDP, far below the 2–4% regional average for non-oil emerging markets. This chronic underperformance stemmed from both legal barriers and reputational concerns. Nationalization policies had created a climate of uncertainty, with foreign-owned firms in banking, insurance, cement, and chemicals expropriated or forcibly merged into state entities without recourse. Rather than encouraging long-term capital formation, Egypt relied heavily on bilateral funding, especially from the Soviet Union, which financed infrastructure and arms but did little to stimulate private enterprise or technology spillovers. Unlike open FDI, this capital was often directed into strategic industries with limited export potential or backward linkages.

The absence of FDI was especially costly in labor-intensive and high-multiplier sectors. In the 1980s, Egypt’s share of global textile and apparel exports was less than 0.15%, despite abundant low-cost labor — while Bangladesh and Tunisia, both smaller and later to liberalize, rapidly expanded their garment sectors through foreign-invested joint ventures. In tourism, Egypt attracted fewer than 1 million visitors annually until the 1990s, far behind peers like Spain and Morocco, in part due to underinvestment in hospitality infrastructure and service training. Crucially, Egypt’s lack of sustained FDI also meant limited integration into global supply chains. By 1995, over 70% of Malaysia’s exports were linked to multinational-led manufacturing, while Egypt remained reliant on primary exports and Suez Canal revenues. The long-term effect wasn’t just capital shortfall — it was a delayed entry into the global economy, with fewer jobs, slower learning curves, and missed opportunities to climb the value chain.

Strategic Assets, Sovereignty, and Statecraft: Comparing the Suez Canal Nationalization to Global Counterparts

Comparing the Suez Canal nationalization with other strategic asset transitions, such as Hong Kong’s port system, the Panama Canal, and especially Saudi Aramco’s phased nationalization, is an insightful way to highlight alternative models of asset control that preserved operational know-how, global integration, and long-term economic value. This comparative lens can illuminate how Egypt’s abrupt nationalization, while symbolically powerful, may have come at the cost of institutional continuity, capital retention, and operational efficiency.

“Al Zaim w Ta’mim Al Canal (Nasser and the Nationalisation of the Canal)” by Hamed Ewais (1957)—This powerful painting depicts Nasser among a crowd at the moment of Suez Canal nationalization — the very act at the heart of economic transformation. Its bold colors and celebratory figures evoke the surge of nationalist pride and sovereignty. The artwork visualizes both the emotional triumph and the institutional rupture that followed—symbolizing how ownership was seized, but technical and commercial continuity was left behind.

The nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956 remains one of the most emblematic acts of post-colonial assertion in the Global South. It galvanized Arab nationalism, challenged imperialist legacies, and momentarily repositioned Egypt as a geopolitical fulcrum between East and West. Yet, as with many bold acts of sovereignty, the long-term economic consequences of the move were shaped less by the symbolism of nationalization and more by how the transition was managed — and what institutional capacity was retained or discarded in the process. When viewed alongside other globally strategic assets — such as Hong Kong’s container ports, the Panama Canal, and Saudi Arabia’s oil sector — Egypt’s approach to the Suez Canal reveals key lessons about the balance between independence and operational integration, symbolism and strategy, ownership and capability.

The Suez Canal: A Symbol of Sovereignty, But at What Operational Cost? At the time of its nationalization, the Suez Canal was operated primarily by French and British interests under the Suez Canal Company. Egypt’s decision to seize control was, in part, a reaction to Western powers’ withdrawal of funding for the Aswan Dam. The political calculus made sense: control the Canal’s revenues to fund national development and assert Egyptian dignity. Yet the move, while defensible from a sovereignty standpoint, triggered a military invasion, capital flight, and most importantly, a rupture in institutional knowledge continuity. The exodus of foreign engineers, administrators, insurers, and legal experts severely disrupted the Canal’s global servicing role, and Egypt had to rebuild much of its maritime logistics and legal support ecosystem from scratch. While the Canal resumed operation relatively quickly, its longer-term modernization and integration into global shipping networks lagged behind comparable ports in Asia.

Hong Kong and Singapore: Sovereignty Without Disruption—Contrast this with Hong Kong’s transformation post-1997. When Britain transferred sovereignty to China, the transition of economic control — especially over its port operations — was executed with institutional continuity in mind. The government of Hong Kong retained the same port authorities, commercial operators, and international legal structures, ensuring that shipping lines, insurers, and logistics providers had confidence in the system. Hong Kong’s container port became (and remains) one of the most efficient in the world, not because sovereignty wasn’t asserted, but because it was exercised without severing operational expertise or international trust. Singapore followed a similar model, where national control went hand-in-hand with high levels of private sector involvement and relentless performance benchmarking. PSA International, the state-owned port operator, was professionalized and structured to compete globally. In both cases, national control was achieved without disrupting capital flows, talent, or trust. The ports became global hubs not because they were nationalized, but because they were internationalized under national control.

The Panama Canal: Gradual Transition, Global Alignment—The Panama Canal offers a third model. The U.S. operated the Canal until 1999 under the terms of the Torrijos–Carter Treaties. The handover to the Panamanian government was structured as a multi-decade transition, allowing time to build domestic capacity and ensure seamless continuation of services. The Panama Canal Authority (ACP), formed in anticipation of the transfer, was built to global standards and retained a non-partisan, technocratic governance structure. Today, the ACP is widely respected for its efficiency and professionalism. Unlike the Suez Canal in the 1950s, Panama’s transition was not abrupt, symbolic, or reactive. It was strategic, phased, and institutionally deliberate. It resulted in a canal that is globally integrated, capital-intensive, and technologically advanced — and which continues to generate sustainable revenue for Panama’s economy.

Saudi Aramco: Phased Sovereignty with Retained Technical Knowledge—Another powerful example comes from Saudi Arabia’s nationalization of Aramco. Beginning in the 1970s, Saudi Arabia gradually acquired stakes in the U.S.-owned oil company, completing the process over nearly a decade. Rather than abruptly replacing foreign staff, the Kingdom emphasized collaboration, training, and long-term knowledge transfer, joint venture models, and capacity building. The result is that Saudi Aramco emerged as one of the world’s most technically advanced, commercially sophisticated national oil companies, commanding immense market power and investor confidence. Even when partially listing on the Tadawul stock exchange in 2019, the company attracted global investor interest due to its transparent governance, retained global partnerships, and operational continuity. Aramco’s nationalization was strategic, not abrupt. It allowed for the cultivation of domestic talent while maintaining the commercial networks and operational rigor that had made it globally competitive.

Egypt’s Missed Opportunity for a Hybrid Model—Had Egypt pursued a phased nationalization of the Suez Canal — retaining foreign expertise through management contracts, joint ventures, or advisory roles — it might have preserved both the economic upside of sovereignty and the technical strengths of global integration. Instead, the immediate post-nationalization years saw Egypt isolated from major capital markets, dependent on Soviet logistical support, and struggling to modernize its maritime infrastructure. Moreover, the Canal’s downstream economic ecosystem — including insurance, arbitration, shipping services, and port logistics — did not grow in tandem. Unlike Singapore or Panama, Egypt failed to turn the Canal into a platform for industrial clustering or services exports. While the Canal today generates an estimated $8–10 billion in annual revenues, its full potential remains underutilized. With better governance, logistical integration, and auxiliary service development, it could plausibly double its economic footprint, especially as global shipping routes shift due to climate, energy, and supply chain dynamics.

The Suez Canal’s nationalization was historic and transformative — but the way it was executed came at a cost. Sovereignty, if pursued abruptly and in isolation, can trigger economic dislocation and knowledge loss. As the comparisons above show, control does not have to mean exclusion. Strategic assets can be nationally owned while still globally connected — as long as the transition is deliberate, informed, and technically grounded. For Egypt today, the lesson is not to undo history, but to relearn the value of global partnerships, institutional continuity, and capacity-building. In an era where Egypt is again seeking to expand the role of the Canal through parallel expansions and logistic zones, a look back at how others nationalized — and why it worked — may help ensure the next chapter is not just symbolic, but transformational.

A Counterfactual Comparison: What If Egypt Had Followed Turkey or Malaysia? Why Egypt’s Peers Pulled Ahead Using Similar Tools More Effectively

To ground our model, we examined the long-term performance of countries that were at similar levels of development as Egypt in the 1950s but took different policy paths. Turkey pursued a mixed model, liberalizing selectively but maintaining state control in key sectors. Malaysia, while influenced by state planning, consistently welcomed FDI and protected private enterprise. By the 2020s: Turkey’s GDP (2025 est.): ~$1.1 trillion, Malaysia’s GDP (2025 est.): ~$550–600 billion, and Egypt’s GDP (2025 est.): ~$425 billion (nominal). Egypt’s counterfactual performance more closely aligns with these peers when adjusted for demographic size and resource base. The implication is clear: with moderate market reforms, Egypt could plausibly have achieved double or even triple its current GDP. This comparison isn’t about glorifying one model over another — it’s about recognizing that macroeconomic structure, investment climate, and institutional incentives matter profoundly over long time horizons.

“On the Path to Revolution” by Zeki Faik İzer (1933) depicts a resolute female figure holding the Turkish flag and walking beside Mustafa Kemal Atatürk—early republican symbols of national renewal. The painting evokes the optimism of a modernizing Turkey that married state-led reform with civic mobilization. Unlike Egypt’s all-encompassing nationalization, Turkey’s transition balanced state direction with openness to private enterprise and foreign capital. This hybrid model laid the groundwork for industrial clusters, export orientation, and robust mid-century growth. The artwork thus visually complements your counterfactual analysis—showing how nuanced economic strategies, not just ideology, can underpin both nation-building and sustainable prosperity.

To contextualize Egypt’s missed economic trajectory, we analyzed the post-1950s development of Turkey and Malaysia—two countries that, like Egypt, emerged from colonial or semi-colonial influence and faced early post-independence nation-building. All three had similar population sizes, GDP per capita, and rural-urban labor divides in the mid-20th century. What explains this divergence is not raw resource endowment or geography—it is the policy architecture. Turkey maintained state ownership in key industries but liberalized its banking and trade regimes earlier, particularly after 1980. Malaysia combined state coordination with strong rule of law protections for private capital and a consistent FDI-friendly posture, especially in electronics and energy. Savings rates and capital formation tell part of the story. Between 1970 and 1990, Malaysia’s gross capital formation averaged 30–35% of GDP, compared to 15–20% in Egypt. Turkey, meanwhile, aggressively restructured its macroeconomic framework in the 1980s, introducing VAT, modernizing its central bank, and opening to capital flows—steps Egypt attempted only in fragmented form decades later.

Additionally, both Malaysia and Turkey managed urbanization more effectively. In 1970, urban dwellers made up just 43% of Egypt’s population compared to 52% in Turkey and 48% in Malaysia—a gap that widened due to underinvestment in urban infrastructure and land-use reform. As a result, Egypt lagged in industrial agglomeration, a key driver of productivity in emerging markets. This is not about romanticizing alternatives, but about illustrating that similar nations made different decisions—decisions that compounded over time. Structural incentives, openness, and institutional reform made the difference between middle-income traps and sustained convergence with high-income status.

Why This Matters Today: Legacy Constraints and Investment Outlook in the Present—Why History Still Shapes the Investment Landscape and Limits Reform Momentum in Egypt Today

This exercise is not a critique of the past — it is a reflection on the present. Many of the constraints Egypt faces today are not simply about current policy choices, but about institutional legacies that trace back to the structural choices of the 1950s and 60s. Understanding this history helps investors navigate today’s market with greater clarity. For example: the dominance of state-owned enterprises and military-linked firms is not new — it’s a continuation, barriers to private sector scale are tied to decades of crowd-out and regulatory asymmetries, and skepticism toward FDI is rooted in historical fears of external control. That said, Egypt is also undergoing meaningful reform. The IMF-backed structural adjustment program, currency liberalization, and public-private partnerships signal a shift. But unlocking Egypt’s full economic potential requires a deeper reckoning with these legacy structures — not just policy tweaks.

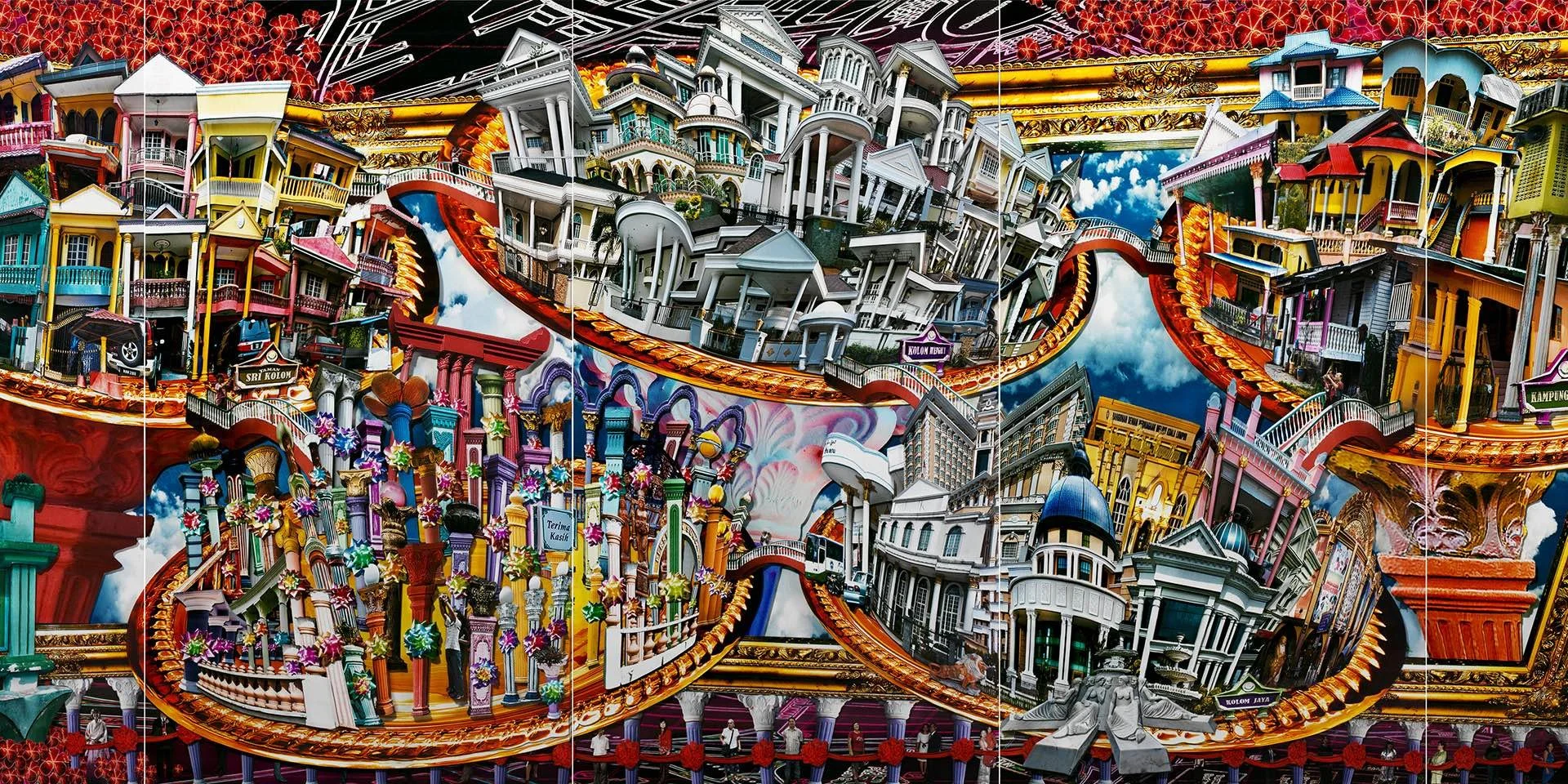

This vibrant and intricately detailed photographic collage by Malaysian artist Liew Kung Yu, titled Bandar Sri Tiang Kolom (2009), exemplifies the grand visual language of Malaysia’s rapid modernization. Part of the Cadangan-Cadangan Untuk Negaraku (“Proposals for My Country”) series and showcased in the Era Mahathir exhibition at Ilham Gallery (2016), the work weaves together hundreds of images to form a fantastical urban landscape—combining kampung houses, neoclassical villas, skyscrapers, and public monuments. The piece celebrates national ambition and architectural excess while critiquing the constructed ideals of progress and identity. Underlying the collage is a narrative of Malaysia’s economic transformation during Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s leadership, when the country pursued aggressive infrastructure development, attracted foreign direct investment (FDI), and positioned itself within global value chains. This work visually supports a powerful counterfactual: had Egypt followed a model more aligned with Malaysia’s—balancing state planning with openness to FDI and private enterprise—it might have seen greater diversification and global integration. The abundance and dynamism of this imagined cityscape contrasts sharply with Egypt’s slower structural evolution, illustrating how policy choices shape not just economies but collective aspirations. Liew’s collage becomes a metaphor for what strategic openness, investment in urban development, and national vision can collectively build.

While Egypt’s economic narrative often focuses on near-term reforms—currency devaluation, privatization pushes, or IMF loan tranches—these are taking place atop decades-old institutional sediment. Many of the patterns constraining Egypt’s current investment climate are not just habits—they are hardened structures born of the post-1952 economic model. The pervasive role of the state in the economy—especially through military-linked enterprises—isn't simply a matter of ideology or power. It’s an administrative legacy. Since the 1960s, economic planning in Egypt has been executed through ministerial decrees, security-reviewed licenses, and centralized budget allocation, creating layers of gatekeeping that continue to burden private investors. As a result, starting a business in Egypt still requires navigating 7–10 separate approvals, far higher than regional peers. The informal economy, which accounts for up to 40–50% of employment, reflects another structural echo. Decades of state overreach pushed much of entrepreneurial life outside the formal system. Today, this shadow economy remains vast but underbanked and underleveraged, limiting tax revenue and scalability. Efforts to formalize these businesses often run into trust deficits—shaped, again, by a historic suspicion of state intervention.

Even the legal environment is a product of hybrid legacies: French-style administrative law, colonial-era codes, and post-Nasserist executive dominance. Commercial dispute resolution can be opaque, and land titling remains fragmented—factors that raise transaction costs and investor risk premiums. What this means is that modern reforms must contend with deep institutional muscle memory. A privatization decree may be issued, but if the land registry is murky or competition from parastatals remains, real change stalls. Understanding this legacy isn’t just academic—it’s essential due diligence. It allows investors, donors, and policymakers to calibrate expectations, identify reform chokepoints, and design interventions that acknowledge the true depth of the challenge.

How This Historical Exercise Can Help Egypt and Its Partners Today: Using Economic Hindsight to Inform Smarter Strategy and Reform—Why Counterfactual Modeling Isn't Just Historical, It's a Strategic Tool for the Future

While the premise of this article is historical, its value lies in how it informs present-day decision-making. Egypt in 2025 is not merely shaped by current reforms — it is operating within the deep structural imprint left by decades of state-centered economic governance. Understanding that legacy is critical for investors, policymakers, and Egyptian reform advocates alike. While the premise of this article is historical, its value lies in how it informs present-day decision-making. Egypt in 2025 is not merely shaped by current reforms — it is operating within the deep structural imprint left by decades of state-centered economic governance. Understanding that legacy is critical for investors, policymakers, and Egyptian reform advocates alike.

Gazbia Sirry’s The Kite (1960) offers a poignant visual metaphor for Egypt’s post-independence trajectory—an era that began with hope but soon became entangled in complexity. A leading figure in the Modern Art Group in Cairo, Sirry often used expressive forms and political symbolism to capture the evolving role of women and the anxieties of a transforming society. In this painting, a fragile, windswept figure clutches the string of a rising kite, caught between flight and collapse. The background sun burns yellow above a stark, blocky building, evoking both aspiration and looming uncertainty. When this work was exhibited at the 1963 São Paulo Biennale under the title al-Khamasīn (“The Sandstorm”), its undertones of turbulence and loss became even clearer. As Egypt confronts its economic future today, this painting resonates as more than a historical artifact—it becomes a metaphor for reform. The fragile balance between momentum and drift, optimism and unease, mirrors Egypt’s current challenge: to avoid repeating cycles of overcentralization, missed opportunity, and unfulfilled potential. Just as the kite could soar or falter depending on how it’s handled, so too can Egypt’s economy—if lessons from the past are integrated into bold, forward-looking reforms. Sirry’s image captures that delicate moment where everything is still possible.

This counterfactual analysis helps in several practical ways: Clarifies Structural Constraints—helps distinguish between challenges caused by temporary factors (e.g. inflation, debt cycles) and those rooted in the deeper architecture of Egypt’s economy — such as inefficient capital allocation, limited competition, or administrative overreach; Builds Investor Confidence Through Context—for international investors, understanding Egypt’s economic backstory can temper unrealistic expectations and also clarify why certain reforms take time. It shifts the question from “Why isn’t this market more open?” to “How do we support its evolution effectively?”; Supports Evidence-Based Policy Design—policymakers can use this kind of retrospective modeling to identify where growth bottlenecks originated — and how to avoid reproducing them. Recognizing the cost of past centralization strengthens the case for deeper private sector empowerment, improved capital markets, and streamlined regulation; and Frames Egypt’s Untapped Potential—by illustrating how Egypt could have achieved far greater growth under different structural conditions, this analysis underscores the latent capacity that still exists. The story is not one of decline, but of delayed potential — and the tools to unlock it are increasingly available.

Counterfactual analysis is often dismissed as speculative or academic. But when grounded in empirical benchmarks, as in this case, it becomes a powerful lens for guiding forward-looking strategy. In Egypt’s context, understanding what could have been is essential to unlocking what still can be. Far from simply describing the past, this kind of modeling helps to prioritize reforms, anticipate resistance, and sequence interventions with greater precision. For policymakers, counterfactual growth trajectories illuminate the true cost of institutional rigidity. For instance, if low private investment cost Egypt 2–3% of annual GDP growth over 50 years, then improving access to capital markets and simplifying regulatory frameworks becomes more than a reform target — it becomes a macroeconomic imperative. This provides a quantifiable rationale for reform, not just a political one. For investors and DFIs, counterfactuals reveal why short-term volatility in Egypt shouldn’t necessarily deter long-term engagement. The fundamentals — location, demography, and industrial potential — were strong enough to plausibly support a $1.2 trillion economy. This helps reposition Egypt from a “risk story” to a “resilience and rebound” story, provided institutional reforms continue. For regional comparators and Egypt’s external partners, this kind of exercise offers diagnostic value. It reveals where development trajectories diverged, and why some reform tools worked in Turkey or Malaysia but stalled in Egypt. This not only refines technical assistance strategies but supports more context-aware conditionality and investment frameworks.

Ultimately, understanding the delta between Egypt’s realized and potential growth is not about blame — it’s about identifying where levers still exist, where momentum is building, and how to align actors around a shared vision of inclusive, competitive prosperity. In short, this article is not an autopsy — it’s a map. A map showing where Egypt might have gone, where it still can go, and what it will take to get there.

Overview of our Methodology and Modeling: How We Built a Counterfactual Growth Estimate and Why It Matters

This analysis was not intended as a speculative critique, but as a grounded exercise in economic modeling to understand the long-term consequences of structural decisions—specifically, Egypt’s embrace of state-led nationalization in the mid-20th century. To build this model, OHK followed a multi-step methodology combining historical GDP data, peer benchmarking, compound growth modeling, demographic and capital formation trends, and a qualitative assessment of institutional divergence. The objective was to project a plausible alternative economic trajectory for Egypt had it followed a more market-oriented, liberalized development path like several of its peers.

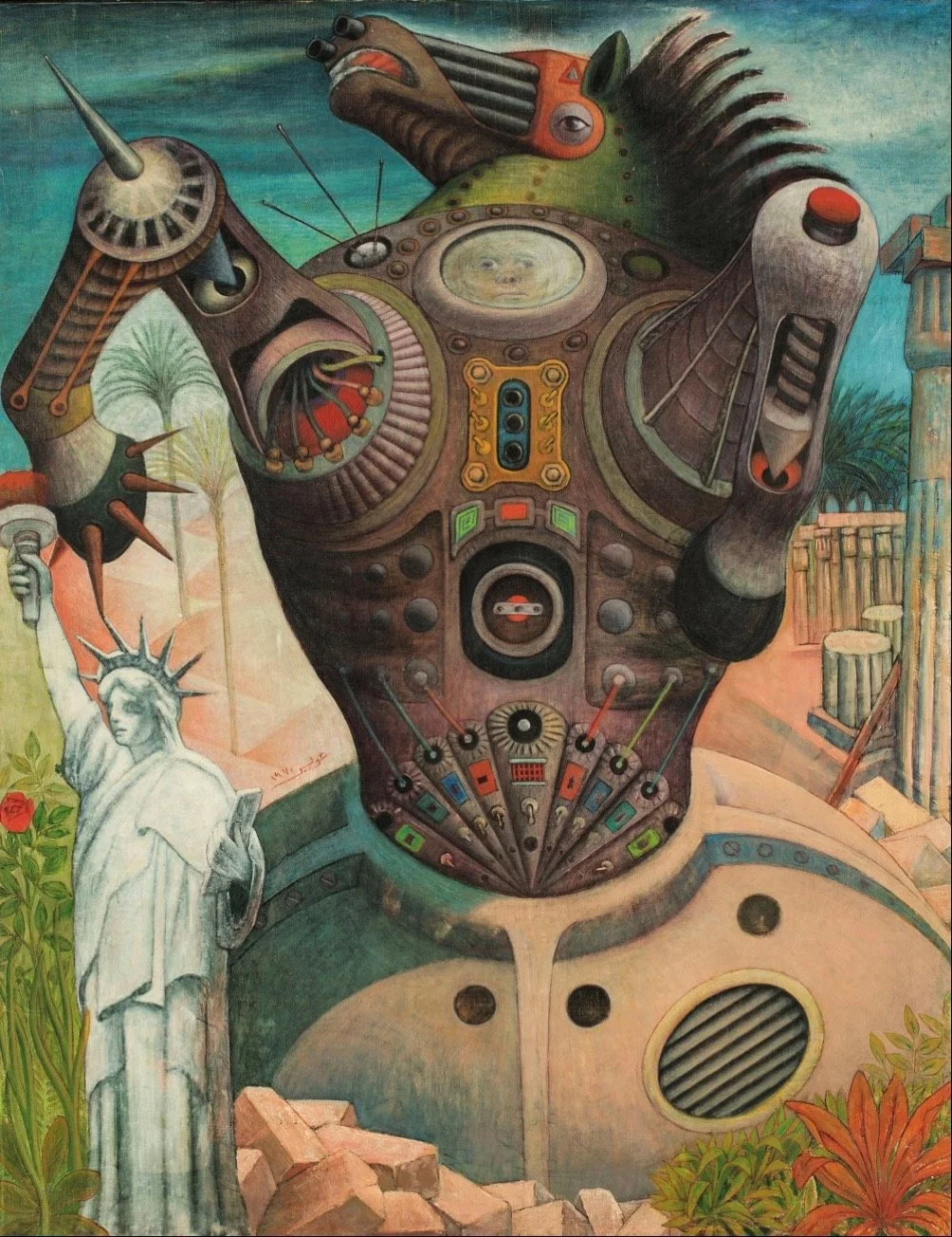

The surreal and dystopian world painted by Hamed Owais in "America" (1984)—with its towering mechanized beast, subdued Statue of Liberty, and shattered ruins—offers more than symbolic critique. It reflects a deeper anxiety about the path nations take when development is driven by imposed power, closed systems, and ideological machinery rather than open markets, competitive institutions, and adaptive governance. We chose to reference this painting not to sensationalize, but to remind the reader that policy decisions—especially structural ones—create lasting imprints on a nation’s economic and institutional landscape. That said, Egypt’s path forward does not have to replicate the American model—or any single model—but it also should not be paralyzed by fear of association with them. Reform is not synonymous with submission, and open markets or institutional liberalization do not equate to cultural or political surrender. Rather, as our analysis shows, the failure to evolve from rigid ideologies has a measurable economic cost—one that Egypt can still choose to reverse.

The first step was establishing a credible economic baseline. We identified the earliest possible reliable dataset for Egypt’s GDP—using 1965 as a reference year due to the availability of World Bank archival data and IMF economic reports. In 1965, Egypt’s real GDP was approximately $20 billion in constant USD. This served as our foundational anchor point for the model. Population data, capital stock estimates, and labor participation rates were pulled from UN historical demographic tables and academic studies on Egypt’s mid-century economy. We also reviewed World Bank and OECD data archives for additional insights into capital formation rates, trade balances, and productivity measures in the region during this period. The next critical task was comparative benchmarking. We identified three comparator countries—Turkey, Malaysia, and South Korea—which, while culturally and geographically distinct, shared similar developmental circumstances in the 1950s and 60s: colonial or semi-colonial legacies, limited industrial bases, and large agricultural labor forces. More importantly, these countries gradually embraced forms of mixed-market development. While Turkey retained state-heavy industries, it liberalized its banking and trade sectors in the 1980s. Malaysia, while pursuing ethnic redistributive policies, consistently welcomed FDI and nurtured export-led industries. South Korea engaged in state coordination but strongly incentivized private sector scale and competition.

By examining these peers, we derived average long-run real GDP per capita growth rates of between 5.5% and 7.2% for the period 1965–2025. We applied this growth range to Egypt’s 1965 GDP and modeled forward using compound growth formulas. To avoid overfitting or optimism bias, we tested three growth scenarios: a moderate growth case (5.5%), a strong but plausible case (6.5%), and an upper-bound comparator (7%) aligned with South Korea’s historical performance. These scenarios produced projected 2025 GDP figures for Egypt ranging from $1.1 trillion to $1.25 trillion, significantly higher than the actual estimate of $425–500 billion. To ensure that this wasn’t a simplistic extrapolation, we also examined capital efficiency, total factor productivity (TFP), and investment-to-GDP ratios for each country over the 60-year period. In Egypt’s case, we observed chronically low capital-output ratios throughout the 1970s and 1980s, despite increased investment. In contrast, Malaysia and Turkey gradually improved capital efficiency, indicating that it was not just the quantity of investment that mattered, but how productively it was deployed—often by private or quasi-private firms rather than by state-led enterprises. These efficiency differentials were built into our adjusted growth estimates.

We also integrated qualitative institutional analysis, drawing on over 30 academic and policy sources. Egypt’s administrative centralization, its prolonged use of price controls, and political allocation of credit were compared to reforms undertaken elsewhere. We reviewed reports by the IMF, UNCTAD, and the Economic Research Forum (ERF), as well as primary legislation related to Egypt’s economic governance. This helped us understand not just economic outputs but the structural mechanics that generated them. What makes this methodology useful beyond Egypt is its portability. Counterfactual modeling of this nature can be applied to any country with a well-documented policy divergence and reliable historical economic data. The process involves: establishing a base-year GDP in real terms, selecting peer countries with similar starting conditions but divergent policy choices; deriving long-run average growth rates and institutional performance metrics from those peers; running forward projections using compound growth, adjusted for demographic, institutional, and capital constraints, and comparing projected outcomes with actual data to estimate the cost—or opportunity—of the divergence.

Of course, this approach is not predictive in a deterministic sense. No counterfactual model can perfectly isolate every shock—wars, commodity cycles, global crises—but that is not its purpose. Its value lies in quantifying the directional impact of long-term structural choices, showing how compounding effects—positive or negative—can profoundly shape national outcomes. In Egypt’s case, the conclusion is clear: while nationalization was ideologically and politically significant, its economic opportunity cost was immense. The absence of a competitive, open, investment-friendly economy—combined with decades of bureaucratic overhang—likely suppressed annual GDP growth by at least 2–3 percentage points for multiple decades. Cumulatively, that gap widened into trillions of dollars in foregone output, job creation, and institutional development. Understanding this gap is not just of academic interest. It is essential for today’s policymakers, who are navigating structural reform under IMF guidance, and for investors, who seek to calibrate risk, potential, and timing. When applied responsibly, this methodology becomes a tool not just for looking backward—but for making smarter decisions going forward.

A Note on Intent: This Is Not Criticism, But a Reflective Exercise on Legacy and Possibility

This article is not offered as a critique of Egypt’s past, but as a reflective exercise grounded in historical and economic analysis. The nationalization policies of the Nasser era were shaped by a complex post-colonial context, driven by a vision of sovereignty, social equity, and national development. Our intention is not to question the motivations behind those policies, but rather to examine their long-term economic implications with the benefit of hindsight. In doing so, we hope this piece serves as a thoughtful starting point — a way to illuminate how structural decisions made decades ago continue to influence Egypt’s economic trajectory today. For investors and policymakers alike, understanding this legacy is key to engaging constructively with Egypt’s evolving market landscape.

Any serious evaluation of Egypt’s post-independence economic path must begin with a recognition of its historical circumstances. The nationalization policies of the 1950s and 60s were not merely administrative choices — they were part of a broader geopolitical and psychological transformation. Egypt, like much of the Global South, emerged from colonial rule with legitimate aspirations for sovereignty, dignity, and control over its own destiny. The move toward a state-led economic model was as much about reclaiming political agency as it was about allocating resources. In that context, nationalization was seen by many as a necessary assertion of independence. The Suez Crisis of 1956, the unequal control of land and industry, and the persistent foreign ownership of key sectors gave urgency to the call for economic justice. These were not abstract decisions — they were felt imperatives in a moment of national trauma and reinvention. This article does not seek to second-guess those motivations. Rather, it seeks to examine how the institutional architecture built in that era — however well-intentioned — has influenced Egypt’s developmental trajectory over the long arc of history. It asks: what were the trade-offs? What was gained, and what was deferred? And most importantly, what lessons can be drawn for today? Understanding this legacy allows us to move beyond simplistic binaries of success or failure. It opens space for constructive engagement — for policy, investment, and reform that is informed not just by ideology or urgency, but by a nuanced awareness of the structural path Egypt has walked. That, in turn, is the foundation for supporting a more inclusive, adaptive, and opportunity-rich economy going forward.

At OHK, we specialize in turning economic complexity into actionable insight. Our team combines rigorous data analysis with scenario-based modeling to help governments, development institutions, and private sector clients understand the long-term impacts of their policy and investment choices. Whether assessing the cost of missed foreign direct investment, modeling the fiscal implications of regulatory reform, or benchmarking national growth performance against global peers, we bring precision, comparability, and strategic clarity to every engagement. Our work draws on robust historical data, comparative international frameworks, and compound growth modeling to surface what traditional forecasts often miss: the opportunity costs of inaction, the structural drag of outdated policies, and the transformative potential of targeted interventions. From base-year calibration and demographic trend integration to capital formation modeling and institutional performance diagnostics, we build models that go beyond numbers—they tell a story about what could be, and what it will take to get there. We don’t just crunch data—we interpret it, challenge assumptions, and design clear, transparent tools for decision-makers navigating uncertainty. Our modeling work has been used to inform structural reform agendas, guide investment strategies, and quantify the long-term returns of good policy. Contact OHK to learn how our economic modeling capabilities can help you make smarter, data-driven decisions for the future.