Who AI Disrupts Most and Who It Barely Touches: Sectoral and National Winners, Losers, and Resilient Economies

A breakdown explaining why AI rapidly reshapes some industries and countries while others remain structurally resilient.

This article is Part II of a three-part blog series on AI, layoffs, and the future of work, following our exploration in Part I of how artificial intelligence is redefining work itself and the ten strategic forces driving organizational redesign and workforce transformation. In this installment, we examine how the impact of AI varies dramatically across sectors and countries, revealing why some industries face significant disruption while others — particularly experience-based and human-centered economies — remain far more resilient. Part III – Beyond Hype: Measuring AI’s Real Impact on Jobs will introduce the analytical framework used to assess automation exposure across industries and economies. Refer to Part I here and Part III here.

Reading Time: 50 min.

All illustrations are copyrighted and may not be used, reproduced, or distributed without prior written permission.

Summary: Part II examines how the impact of artificial intelligence on jobs is uneven across sectors and countries, showing that automation reshapes some economies far more rapidly than others. It presents a sectoral exposure ranking that highlights why technology, finance, professional services, and customer support face the highest disruption, while tourism, hospitality, and experience driven industries remain largely resilient. The article also explores national differences, including emerging markets and GCC countries, where rapid AI adoption promises productivity gains but carries significant workforce transition risks due to skills gaps and unemployment pressures.

The Tide of AI Does Not Rise Evenly. Artificial intelligence flows first into digitized, process-heavy economies, where routine cognitive work is already standardized and scalable, rapidly compressing corporate labor. It reshapes industrial and logistics systems next, automating tasks while physical operations slow full displacement. But as the tide reaches experience-based and human-centered sectors, its force weakens. Hospitality, culture, care, and relational services remain anchored in human presence, trust, and judgment, where automation augments rather than replaces. The future of work is not a universal flood. It is a selective current, reshaping some shores quickly, eroding others gradually, and barely touching those built on human connection. AI transforms where work is digital — and slows where work is human.

Sectoral Exposure to AI: Why Some Industries Will Feel the Shock Far More Than Others

One of the most overlooked realities in the AI-driven restructuring wave is that its impact is not evenly distributed across industries. While highly digitized, process-heavy corporate environments are already experiencing measurable workforce compression, sectors built around human presence, emotional interaction, trust, and lived experience remain far more resilient. At the sector level, AI exposure is shaped by four core structural factors. The first is the degree to which work is digital and standardized, making it easier to automate at scale. The second is how heavily daily tasks rely on routine cognition, such as processing information, following rules, and executing predictable workflows. The third is how much value creation depends on human judgment, creativity, empathy, and real-world interaction, which remain difficult to replicate technologically. The fourth is regulatory intensity, which governs how quickly automation can be deployed, how much human oversight must remain, and how much risk organizations can absorb when systems fail. Where work is highly digital, repetitive, and lightly regulated, AI substitution accelerates rapidly. Where work is relational, high-trust, or tightly governed by legal and safety frameworks, automation tends to augment rather than replace, compressing administrative layers while preserving human accountability.

The highest exposure emerges in digitally native, process-heavy service sectors, where work is already standardized, data-driven, and scalable. Industries such as information and communication services, financial and insurance activities, professional and technical services, and administrative and support operations concentrate large volumes of routine cognitive labor, from coding and analytics to compliance processing, customer support, research, and documentation. In these environments, AI can absorb entire task clusters rapidly, generating immediate productivity gains and making workforce compression economically rational when workflows are redesigned properly. This is why technology firms, banks, consultancies, and large service platforms are consistently at the center of AI-driven layoffs. A second tier of moderate exposure appears across manufacturing, logistics, utilities, construction, transportation, and real estate, where automation optimizes forecasting, monitoring, quality control, routing, and planning but is constrained by physical infrastructure, capital intensity, and real-world execution. Here, AI reshapes roles far more than it eliminates entire job categories, compressing specific processes while preserving human oversight, maintenance, and operational judgment.

Disruption slows further in highly regulated and accountability-driven sectors, particularly public administration, education, and healthcare services. Although AI increasingly automates records processing, scheduling, diagnostics support, and compliance workflows, strong governance frameworks, legal liability, safety concerns, and trust requirements keep humans embedded at the core of decision-making and service delivery. In these domains, automation largely augments rather than replaces labor, compressing administrative layers while preserving frontline human responsibility. At the lowest end of displacement exposure sit experience-based and human-centric industries, including hospitality, tourism, retail service, arts and entertainment, and personal services. In these sectors, human interaction is not a cost inefficiency but the product itself. Emotional connection, storytelling, trust, creativity, and presence drive value creation, and automation often degrades rather than enhances customer experience. While AI improves bookings, payments, logistics, and back-office efficiency, large-scale replacement of frontline labor remains economically counterproductive.

OHK finds AI disruption follows economic structure, not hype, accelerating in routine digital sectors and slowing where human value dominates.

Primary and extractive sectors such as agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining, and quarrying occupy an intermediate position, where AI boosts productivity through monitoring, predictive systems, and precision operations but rarely eliminates large workforces outright. Finally, informal household economies and international organizational work see limited displacement beyond administrative automation, as human labor remains structurally embedded. The result is a highly uneven transformation of work across industries. AI compresses routine cognitive labor most aggressively, moderately reshapes process-heavy physical operations, and barely touches experience-driven human services in the near term. Understanding this uneven sectoral exposure is essential for interpreting current workforce reductions and for designing realistic transition strategies. The future of work will not be shaped by technology alone, but by how different industries fundamentally create value—through automation where tasks are routine, and through people where human experience remains irreplaceable.

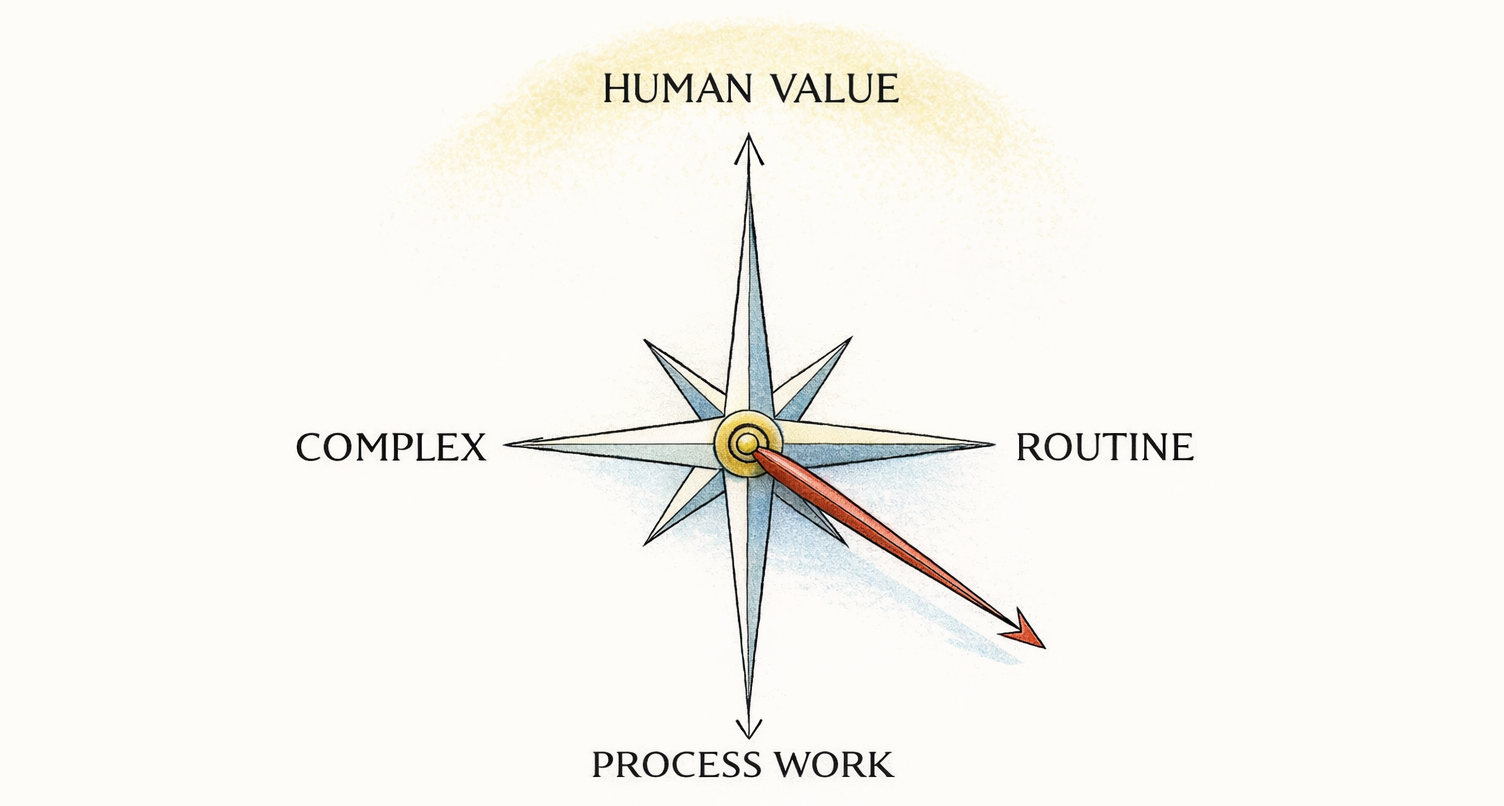

The Compass of Disruption illustrates how AI does not transform work randomly, but follows the underlying structure of tasks. The horizontal axis contrasts complex, adaptive work with routine, standardized processes, while the vertical axis distinguishes human value from process work focused on execution. The needle’s pull toward the lower-right quadrant reflects where automation accelerates fastest—where tasks are predictable, digital, and easily codified. By contrast, the glowing upper region signals domains grounded in judgment, trust, creativity, and human presence, where AI primarily augments rather than replaces. The message is clear: AI follows structure, not hype—reshaping work where efficiency dominates and reinforcing human roles where value cannot be automated.

How to Read AI Exposure: This diagram frames AI disruption risk not as a single force, but as the intersection of four structural drivers that shape how, where, and how fast work can be automated: digital feasibility, task structure, human value, and regulatory friction. Together, they explain why AI transforms some sectors rapidly while barely touching others. At the core of the map is a 2×2 exposure framework defined by task structure and human value. The horizontal axis captures task structure, ranging from complex, adaptive, and judgment-heavy work on the left to highly rules-based, repeatable, and standardized work on the right. The vertical axis captures human value, ranging from execution and coordination at the bottom to judgment, empathy, creativity, trust, and presence at the top. The upper half of the map represents the augmentation zone, where human value is high and work depends on context, trust, lived interaction, and accountability. In this zone, AI improves speed, insight, consistency, or reach, but cannot replace humans without destroying value. Healthcare delivery, tourism, leadership, education, and creative strategy sit here. Automation supports professionals, but human presence remains the product. This zone is also where regulatory and ethical constraints are strongest. High-stakes outcomes, public trust, liability exposure, and professional standards act as natural brakes on full automation. As a result, even when tasks are partially digitized, AI adoption here tends to be assistive, supervised, and slow-moving.

The lower half represents the displacement zone, where work is heavily routine and human contribution is primarily executional. Tasks are predictable, outcomes are measurable, and accountability can be embedded in systems rather than people. In these areas, AI can replace large volumes of work outright. Customer support, finance operations, administration, compliance processing, and junior knowledge work fall here, explaining why these sectors are seeing the fastest and deepest workforce compression. Importantly, regulatory friction is weakest here. Rules are already codified, decisions are auditable, and substitution risk is low. Regulation often accelerates automation by encouraging standardization rather than resisting it.

Between augmentation and displacement sits a broad reshaping zone, where AI does not eliminate work outright but fundamentally changes how it is organized. In this zone, automation absorbs clusters of routine tasks, compresses management and coordination layers, and redesigns workflows around smaller, higher-leverage teams. Headcount often declines, but human roles persist as oversight, judgment, exception handling, and integration points. This is where many sectors currently sit. In the illustration, this reshaping zone is not drawn as a separate band to preserve clarity and readability. Instead, it is implied as the transitional space between augmentation and displacement, emphasizing direction of change rather than forcing artificial boundaries.

OHK observes AI disruption emerges at the intersection of task structure, human value, digital feasibility, and regulatory friction.

Acceleration and Friction Forces—Two additional forces shape the speed and severity of disruption across both zones. First, Digital standardization acts as an acceleration factor. Fully digital environments can automate in months, while physical or hybrid services take years. Second, Regulatory intensity acts as friction. Where regulation emphasizes safety, trust, ethics, and human accountability, AI is constrained to augmentation. Where regulation emphasizes consistency, compliance, and auditability, automation is often enabled rather than blocked.

Reading the Map as a Whole—The highest displacement risk sits where work is digital, routine, low in relational value, and lightly governed. The greatest resilience appears where work is human, contextual, high-stakes, and regulated. Most sectors fall between these extremes, where AI reshapes workflows, compresses layers, and reassigns responsibility rather than eliminating humans outright. The central insight is simple: AI follows the structural economics of work, not hype. Regulation does not stop automation uniformly; it redirects it. Where risk, trust, and accountability matter most, AI augments. Where efficiency and standardization dominate, AI replaces. AI does not disrupt randomly. AI follows the structural economics of work, not hype.

This conceptual city map visualizes AI exposure across the full UN ISIC economic system (A–U), showing how automation pressure clusters structurally rather than spreading evenly. The dense digital core represents sectors where work is highly standardized, digitally feasible, and lightly governed, driving the fastest workforce compression. Surrounding industrial districts reflect task automation and workflow redesign without full displacement, while outer human-centered neighborhoods highlight where judgment, experience, trust, and creativity anchor resilient work. Lighter governance zones illustrate how regulatory friction slows substitution in critical systems. The graphic is conceptual rather than predictive, revealing the structural logic shaping where AI reshapes work first — and where humans remain essential. How to Read the Sectoral AI Exposure Map (Color Logic)? 🔴 Red – Displacement Zone: Sectors dominated by highly digital, routine, and lightly governed work, where AI can replace entire task clusters rapidly. These industries experience the fastest workforce compression as automation substitutes large volumes of cognitive labor directly. 🟠 Orange – Reshaping Zone: Sectors where AI automates specific processes and task clusters but remains constrained by physical infrastructure, safety requirements, and capital intensity. Here, work is redesigned and layers are compressed, yet humans remain embedded in operations and oversight. 🟢 Green – Augmentation Zone: Industries built around human judgment, trust, creativity, and lived interaction, where automation primarily supports rather than replaces labor. AI improves efficiency and coordination, but removing humans would destroy value rather than enhance it. ⚪ Light Neutral – Primary & Contextual Work: Sectors grounded in physical environments, biological systems, and relational labor, where digital feasibility remains limited and automation progresses slowly.

AI Exposure by UN ISIC Economic Sector (A–U)

Sectoral Exposure to AI Across the Full Economy (UN ISIC Framework): To move beyond isolated disruption stories and assess how artificial intelligence is truly reshaping work at scale, OHK mapped automation exposure across the full economy using the United Nations’ International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC), which spans 22 core sectors from agriculture and mining to high-tech services, public administration, creative industries, and experience-based economies. This comprehensive lens reveals that AI disruption is not random or evenly distributed, but follows a clear structural logic shaped by digital feasibility, task routinization, human value dependence, and regulatory friction.

OHK observes AI does not disrupt industries evenly — it compresses routine digital work first and reshapes or spares human-centered sectors.

Taken together, the full ISIC economy reveals a consistent pattern: AI compresses routine digital labor most aggressively, moderately reshapes process-heavy physical operations, and barely touches relational, experiential, and highly governed work in the near term. Disruption accelerates where tasks are standardized and scalable, and slows where value depends on human judgment, trust, creativity, and physical presence. The strategic implication is clear. AI is not a universal job destroyer. It is a selective productivity engine. Layoffs surge in sectors built on routine cognition and digital throughput, while industries rooted in human experience remain comparatively resilient. Understanding this uneven sectoral exposure is essential for interpreting current workforce reductions and for designing realistic transition strategies. The future of work will not be shaped by technology alone, but by how different industries fundamentally create value, through automation where tasks are procedural, and through people where human experience remains irreplaceable.

To move beyond abstract discussions of “AI disruption,” OHK mapped exposure across the full United Nations ISIC economic classification system, covering every major sector of the global economy from agriculture to high-tech services and public institutions. Each sector’s position reflects the interaction of four structural forces: how digitally standardized the work is, how routine and rules-based daily tasks tend to be, how central human judgment and lived interaction are to value creation, and how strongly regulation and governance constrain automation speed. Where work is highly digital, repetitive, and lightly governed, AI substitution accelerates rapidly and workforce compression is already visible. Where work is physical, relational, creative, or tightly regulated, automation primarily augments rather than replaces human labor. Most sectors fall between these extremes, experiencing role reshaping rather than wholesale displacement. The result is a highly uneven transformation of work across industries, with some facing rapid compression and others remaining structururally resilient in the near to medium term.

OHK finds AI acts as a selective productivity engine — eliminating standardized cognition while preserving value rooted in human judgment and experience.

To ground this framework in real operational outcomes rather than theory, OHK paired each ISIC sector with concrete real-world evidence, highlighting one example where AI deployment has successfully improved productivity or efficiency and one where over-automation, poor sequencing, or misplaced substitution assumptions produced failure, risk, or value erosion. This dual lens reveals not only where automation delivers genuine leverage, but also where removing human judgment, accountability, or physical presence has backfired. Together, these success-and-failure case contrasts demonstrate that AI’s impact is not simply a question of technological capability, but of structural fit between automation and how each sector actually creates value.

A. Agriculture, forestry & fishing – Augmentation zone: AI supports precision farming, monitoring, and forecasting, but biological uncertainty, environmental variability, and reliance on human judgment limit full automation of physical and seasonal work. Companies like John Deere use AI for precision planting, yield forecasting, and equipment automation, dramatically improving efficiency. What does not work is fully automating harvesting decisions, crop health judgment, or adapting to unpredictable weather and soil conditions, where farmers’ experience remains critical. Even advanced deployments by IBM in AI-driven weather and yield prediction have struggled when climate volatility exceeded historical data patterns. AI models failed to anticipate extreme events, forcing farmers to override automated recommendations. What didn’t work: replacing farmer judgment in unpredictable biological systems.

B. Mining & quarrying – Reshaping zone: AI improves exploration, safety monitoring, logistics, and predictive maintenance, yet capital intensity, hazardous environments, and physical extraction requirements prevent large-scale labor elimination. Firms such as Rio Tinto deploy AI for autonomous haul trucks, exploration analytics, and safety monitoring. What does not disappear is physical extraction work, hazardous-site supervision, and capital-intensive operations that still require human teams. At Anglo American, early autonomous mining trials showed productivity gains but faced repeated shutdowns due to sensor failure and unexpected geological conditions. What didn’t work: assuming autonomy could fully replace human supervision in hazardous, variable environments.

OHK finds that AI succeeds where automation aligns with how value is actually created—and fails fastest where it tries to replace human judgment, context, and accountability.

C. Manufacturing – Reshaping zone: Robotics and AI automate repetitive production steps and quality checks, but complex assembly, maintenance, exception handling, and system supervision continue to require human oversight. Companies like Toyota Motor Corporation automate assembly steps, quality inspection, and predictive maintenance with AI-driven robotics. What cannot be fully automated is complex troubleshooting, custom production adjustments, and system oversight. Tesla famously over-automated its production lines in early Model 3 manufacturing, leading Elon Musk to admit “excessive automation” was a mistake. What didn’t work: removing human flexibility from complex assembly too early.

D. Electricity, gas, steam & air conditioning – Reshaping zone: AI optimizes grid management, demand forecasting, and outage detection, while high infrastructure risk, regulatory oversight, and safety requirements constrain workforce displacement. Utilities such as National Grid use AI for grid balancing, outage prediction, and demand forecasting. What remains human-led is infrastructure safety, emergency response, and regulatory accountability. AI-driven grid automation at PG&E failed to prevent catastrophic outages and wildfires, revealing that automation without governance and maintenance oversight increases systemic risk. What didn’t work: substituting human accountability in safety-critical infrastructure.

E. Water supply, sewerage & waste management – Reshaping zone: Automation enhances monitoring, optimization, and compliance reporting, but physical infrastructure operations and environmental risk management remain human-dependent. Organizations like Veolia apply AI to monitor leaks, optimize treatment plants, and track compliance. Physical repairs, environmental risk response, and field operations still rely on human crews. Smart monitoring systems deployed by Thames Water failed to prevent leaks and service disruptions due to poor physical infrastructure. What didn’t work: assuming AI optimization can compensate for aging assets and underinvestment.

F. Construction – Reshaping zone: AI accelerates design, planning, and cost estimation, yet on-site execution, coordination, and safety-sensitive physical labor resist full automation. Firms such as Bechtel use AI for project planning, cost modeling, and risk forecasting. What does not automate is on-site building, safety management, and real-time coordination of physical labor. AI-driven project planning tools adopted by Katerra could not overcome real-world coordination failures, contributing to the firm’s collapse. What didn’t work: treating construction as a purely digital optimization problem.

OHK finds that in capital-intensive and physical systems, automation delivers its greatest value in prediction and process optimization, while full labor substitution repeatedly breaks down under complexity, risk, and real-world variability.

G. Wholesale & retail trade – Reshaping zone: AI automates inventory management, pricing, demand forecasting, and logistics, while physical handling and customer-facing roles continue to rely on human presence. Companies like Walmart automate inventory, pricing, and demand prediction with AI. But physical stocking, in-store service, and customer interaction remain largely human. Amazon’s Amazon Go stores struggled to scale globally due to edge cases in customer behavior and high operational costs. What didn’t work: fully automated retail without sufficient human fallback.

H. Transportation & storage – Reshaping zone: Routing, scheduling, and warehouse optimization are increasingly automated, but physical transport, infrastructure constraints, and safety considerations slow full displacement. Logistics leaders such as DHL use AI for route optimization and warehouse robotics. Yet drivers, port operations, and infrastructure-dependent roles decline slowly rather than vanish. Autonomous trucking pilots by TuSimple stalled after safety incidents and regulatory scrutiny. What didn’t work: eliminating human drivers in complex public-road environments too early.

I. Accommodation & food services – Augmentation zone: Human interaction, service quality, and experiential value define the product, making automation primarily a back-office support tool rather than a labor replacement engine. Hospitality brands like Marriott International use AI for bookings, pricing, and operations. What clearly doesn’t work is replacing hospitality, service warmth, and guest experience with automation. Robot waitstaff trials by Zume failed commercially as customers rejected the experience and costs ballooned. What didn’t work: replacing hospitality with automation in experience-driven services.

J. Information & communication – Displacement zone: Highly digital workflows in content creation, software development, analytics, and media processing are strongly automatable, driving rapid compression of routine knowledge work. Firms such as Google increasingly rely on AI for content moderation, coding assistance, data analysis, and media processing. Entire layers of routine digital knowledge work are being compressed. AI-generated content experiments at CNET produced factual errors and credibility damage, forcing retractions. What didn’t work: removing editorial oversight from automated content production.

K. Financial & insurance activities – Displacement zone: High-volume rule-based processing, underwriting, compliance, and documentation automate efficiently under controlled governance, enabling significant workforce reduction. Institutions like JPMorgan Chase automate contract review, fraud detection, underwriting support, and operations at scale. What remains human is complex judgment, client relationships, and regulatory responsibility. Call center automation at Bank of America initially reduced costs but triggered customer frustration and escalation overload. What didn’t work: cutting human agents before AI resolution quality stabilized. Also, Automated credit decisions at Zest AI and similar platforms have faced regulatory scrutiny over bias and explainability. What didn’t work: replacing human judgment in opaque, high-stakes decisions.

Across service logistics and experience-based industries, AI reshapes operations while preserving human presence, but once workflows become entirely digital and rules-based, substitution accelerates rapidly and workforce compression becomes economically unavoidable.

L. Real estate – Reshaping zone: Valuation, listings, and transactions digitize rapidly, but physical assets, negotiation, and relationship-driven activity preserve human roles. Platforms such as Zillow use AI for pricing, listings, and market analytics. But negotiation, asset management, and trust-based transactions still center on people. On the other hand, Zillow shut down its AI-driven home-buying business after algorithmic pricing errors caused massive losses. What didn’t work: assuming AI valuation models could replace market judgment at scale.

M. Professional, scientific & technical activities – Displacement zone: Research, modeling, analysis, drafting, and documentation increasingly compress junior and routine knowledge roles, reshaping the traditional professional pyramid. Firms like Deloitte now deploy AI for research, audit analytics, drafting, and modeling. Junior analytical layers shrink rapidly, while senior advisory judgment remains human. Law firms using early AI contract review platforms such as RAVN Systems found that over-automation increased legal risk in complex agreements, forcing firms to reinstate human review layers. What didn’t work: removing junior legal judgment before accountability systems were redesigned.

N. Administrative & support services – Displacement zone: Scheduling, processing, customer support, and coordination tasks are highly standardized and digitally feasible, making them prime targets for automation. Companies such as Teleperformance are replacing large volumes of scheduling, processing, and customer service tasks with AI-driven automation. Large enterprises that rushed full chatbot replacement in customer operations — including early deployments at Air Canada — faced legal action after AI agents gave incorrect policy information. What didn’t work: eliminating human escalation in standardized but high-impact service interactions.

O. Public administration & defense – Augmentation / Reshaping zone: Bureaucratic workflows digitize slowly due to regulation, accountability, security, and political risk, limiting rapid displacement while reshaping administrative functions. Governments like the United States Department of Veterans Affairs automate claims processing and records management, but policy decisions, security, and accountability remain human-led. Automated benefits systems used by the Government of the Netherlands led to wrongful accusations and social harm in welfare fraud detection. What didn’t work: automating enforcement without human review.

Where corporate services prioritize efficiency and scalability, AI substitution accelerates; where work is governed by public responsibility, legal liability, and political risk, automation shifts from replacement to cautious augmentation.

P. Education – Augmentation zone: AI supports content delivery, assessment, and administration, but teaching, mentorship, and social development remain fundamentally human-centered. Institutions such as Coursera use AI for content personalization and assessment, while teaching, mentorship, and social development stay human-centered. AI proctoring systems used by ProctorU were widely criticized for bias and false positives. What didn’t work: replacing trust and pedagogy with surveillance automation.

Q. Human health & social work – Augmentation zone: Clinical judgment, care delivery, trust, and ethical accountability anchor human roles, even as administrative and diagnostic support functions automate. Healthcare systems like Mayo Clinic use AI for diagnostics support and scheduling, but clinical judgment, care delivery, and patient trust cannot be automated away. IBM’s Watson Health failed to deliver reliable clinical decision support, leading to its sale. What didn’t work: substituting medical judgment with immature AI systems.

R. Arts, entertainment & recreation – Augmentation zone: Creativity, cultural expression, and emotional engagement resist substitution, with AI acting mainly as a tool rather than a replacement. Studios such as Disney use AI in animation tools and content analytics, but storytelling, creativity, and emotional engagement remain human-driven. AI-generated music platforms like Boomy faced backlash from artists and platforms over originality and rights. What didn’t work: replacing creativity without cultural legitimacy.

S. Other service activities – Reshaping zone: Mixed automation of scheduling, billing, and support functions occurs alongside persistent demand for personal, relational services. Companies like Mindbody automate bookings, payments, and scheduling while personal services themselves remain human. Automated scheduling tools in personal services used by StyleSeat improved logistics but failed when overused without human flexibility. What didn’t work: rigid automation in relationship-based services.

T. Household employment & self-production – Augmentation zone: Informal, relational, and context-specific work remains largely non-automatable due to low digital feasibility and high human dependence. Platforms such as Care.com use AI for matching and logistics, but caregiving, cleaning, and personal support remain fundamentally human. Home-care automation attempts by iRobot illustrate limits: devices assist but cannot replace caregiving or household judgment. What didn’t work: substituting relational domestic labor.

U. Activities of international organizations – Reshaping zone: Administrative and reporting functions automate, while diplomacy, coordination, negotiation, and governance remain human-led. Institutions like the United Nations automate reporting, data analysis, and administration, while diplomacy, negotiation, and coordination stay human-led. AI-driven aid allocation models piloted by World Food Programme required human override when local context diverged from model assumptions. What didn’t work: fully automated decision-making in humanitarian operations.

Many sectors confirm that AI disruption is bounded by human value density. Where outcomes depend on trust, legitimacy, empathy, moral judgment, or cultural meaning, automation cannot replace responsibility without eroding the very value being delivered. In these domains, over-automation repeatedly fails not because the technology is weak, but because the economic structure of the work resists substitution.

Together, the letters A through U represent the official sector identifiers used in the United Nations’ International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) system, which serves as the global framework for organizing all economic activity. Each letter corresponds to a major economic sector spanning the full economy, from primary industries such as agriculture and mining to advanced services, public administration, and international institutions. These codes are not rankings or impact scores, but standardized sector IDs used by governments, statistical agencies, and international organizations to track employment, productivity, and economic structure consistently across countries. Using ISIC classifications ensures that AI exposure analysis aligns with how national economies are actually measured, allowing comparisons across regions, industries, and development levels rather than relying on informal or subjective sector groupings.

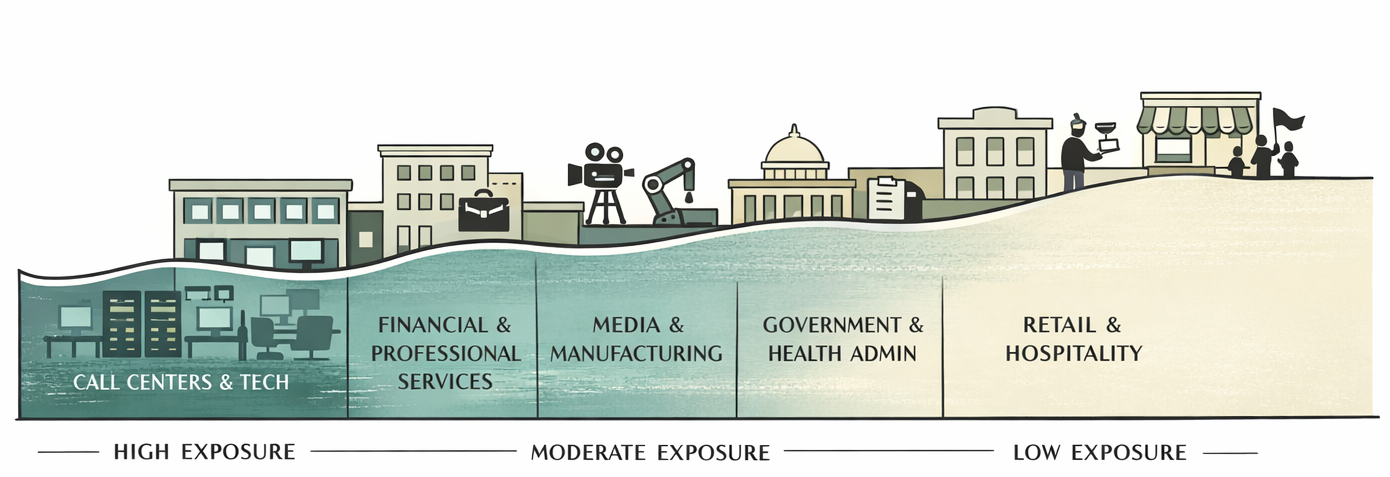

Not all work sits at the same elevation. Like a rising tide, artificial intelligence does not reach every shoreline equally. It flows first into the most structured, digitized, and routine forms of work submerging call centers, technology services, finance, and professional back offices while slowing across manufacturing floors and administrative systems. Higher ground remains where human presence itself creates value: hospitality, frontline retail, tourism, culture, and experience-based economies. AI reshapes the landscape not through sudden collapse, but through gradual, uneven exposure, revealing which kinds of work were built for machines and which endure because they are irreducibly human.

Methodology Box—How OHK Estimates AI Displacement Exposure: The Research Backbone Behind OHK’s AI Impact Framework

OHK’s displacement exposure estimates are based on task-level analysis rather than headline job counts. The methodology begins by decomposing each sector into its major roles and then breaking those roles into core tasks. Each task is evaluated against five structural criteria: digitizability, routineness, standardization, regulatory/privacy constraints, and degree of human-essential interaction (e.g., empathy, trust, physical presence). Tasks are assigned an AI feasibility score (0–1) using a weighted model calibrated to observed automation patterns. That feasibility score is then adjusted by a substitution factor, distinguishing between tasks likely to be replaced versus augmented. Role-level exposure equals the weighted share of time spent on substitutable tasks. Sector-level exposure is calculated by aggregating across roles using employment weights. Finally, results are expressed as ranges rather than point estimates, incorporating scenario adjustments for adoption friction (capital, regulation, integration lag) and role redesign retention (tasks reabsorbed into higher-value human functions). Importantly, percentages reflect technical automation feasibility of work-hours, not projected job losses.

Note: The sectoral exposure estimates presented here in Part II are derived from OHK’s Displacement Exposure Index (DEI), a task-level measure of automation feasibility that captures the structural vulnerability of work to AI substitution. DEI is explored in full methodological depth in Part III as a core pillar of OHK’s multi-dimensional impact framework.

OHK’s displacement exposure model is grounded first and foremost in task-based automation research, led by institutions such as McKinsey & Company and the OECD, alongside academic labor economists. This body of work fundamentally shifted automation analysis away from asking whether entire jobs disappear toward measuring which tasks within jobs can be automated. McKinsey’s landmark studies (beginning in 2017 and refined through 2023) quantified the share of work-hours across occupations that are technically automatable, showing that most roles face partial transformation rather than full replacement. In parallel, OECD research — notably by Nedelkoska and Quintini — statistically modeled automation probability at the task level, linking digitization, routineness, and standardization to technological feasibility. This task-decomposition logic is the direct backbone of OHK’s approach.

Earlier headline-grabbing models came from University of Oxford researchers Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne, who estimated the probability of computerization by occupation in 2013 — producing the famous claim that roughly 47% of U.S. jobs were at high risk. While historically important, that model treated occupations as single units rather than bundles of tasks, which later research showed tends to overstate displacement. OHK’s framework is explicitly more granular, aligning with the newer task-based consensus.

A third foundational pillar comes from technology diffusion and industrial economics, which consistently distinguishes between technical feasibility, economic adoption, and organizational redesign. Even when automation is possible, real-world uptake is shaped by capital costs, regulation, integration complexity, labor institutions, and risk management — explaining why exposure does not translate directly into layoffs.

Where OHK Extends the Literature (the original synthesis)? Building on these streams, OHK introduces several integrating layers that are not found together in any single prior model: (i) a clear separation between technical feasibility (f) and actual substitution versus augmentation (k), (ii) a redesign retention factor (G) capturing how automated time is absorbed into higher-value human work rather than eliminated, (iii) expressing outcomes as scenario-based ranges driven by adoption friction and organizational response, and (iv) reframing results as “displacement exposure” (structural vulnerability of work-hours) rather than sensational job-loss forecasts.

OHK’s displacement exposure framework builds directly on task-based automation research and academic labor economics, incorporates diffusion-economics distinctions between feasibility and adoption, and extends these through proprietary substitution and redesign adjustments to model structural exposure rather than headline job loss.

OHK estimates that at the higher end of indicative impact potential are Customer Support & Call Centers (45–65%) and Technology & Software Services (40–55%), followed by Financial Services & Insurance (35–50%) and Professional Services including Consulting, Legal, and Accounting (30–45%). Media, Content & Marketing (25–40%) and Manufacturing & Logistics (20–35%) show moderate exposure, alongside Government Administration (20–30%) and Healthcare in non-clinical roles (15–25%). More structurally resilient sectors include Retail Frontline & Hospitality (5–15%) and Tourism, Culture & Experience Economies (3–10%), where human presence, physical interaction, and experiential value limit automation depth.

In this context, displacement refers to the share of roles within a sector that have high technical feasibility for automation or AI substitution of core tasks, particularly routine, rules-based, or digitizable functions. It does not imply direct or immediate layoffs. Rather, these percentages reflect automation exposure potential—the proportion of work activities that could technically be automated under current or near-term AI capabilities. As such, the figures indicate structural vulnerability, not total job loss projections, since many roles will be augmented, redesigned, or partially automated rather than eliminated outright.

In Technology & Software Services, AI now automates code generation, testing and debugging, documentation, infrastructure monitoring, and analytics, compressing entire junior and mid-level engineering workflows; here, displacement is structural rather than cyclical, as AI materially multiplies output per engineer. In Financial Services & Insurance, automation increasingly covers risk modeling, underwriting, fraud detection, compliance monitoring, customer inquiries, and reporting, with AI reducing processing times from days to seconds, though human oversight remains essential in complex and regulated cases. Within Professional Services such as Consulting, Legal, and Accounting, AI performs research, contract review, financial modeling drafts, market analysis, and document preparation, compressing the traditional pyramid model and placing pressure on junior analyst pipelines that historically produced future experts.

In Customer Support & Call Centers, exposure is among the most immediate and pronounced, as AI handles FAQs, troubleshooting scripts, account changes, scheduling, and escalation triage, making large portions of tier-one support highly automatable due to predictable, high-volume workflows. Media, Content & Marketing faces moderate to high exposure through AI-generated copy, ad creatives, SEO content, social posts, and campaign analytics, though brand strategy, storytelling, cultural nuance, and creative direction remain human-dominant. Manufacturing & Logistics sees task-level automation in warehouse operations, quality control, predictive maintenance, and routing, yet capital intensity and physical infrastructure constraints moderate full-role displacement.

In Government Administration, AI increasingly supports permitting, records processing, benefits administration, and compliance checks, but regulatory caution and political accountability slow transformation. Healthcare in non-clinical roles experiences automation in scheduling, billing, documentation, diagnostics support, and claims processing, while frontline care remains deeply human-centered. Exposure is comparatively low in Retail Frontline & Hospitality, where customer experience, emotional interaction, and brand perception are intrinsic to revenue generation, making humans part of the product itself. Finally, Tourism, Culture & Experience Economies show the lowest exposure, as demand centers on personal service, storytelling, authenticity, hospitality, and emotional connection; here, AI primarily enhances back-office efficiency rather than replacing labor.

Across all sectors, displacement refers to the share of roles with high technical feasibility for AI substitution of core tasks, particularly routine, digitizable, or rules-based activities. These assessments reflect automation exposure potential rather than direct job-loss projections, as many roles will be augmented, redesigned, or partially automated rather than fully eliminated.

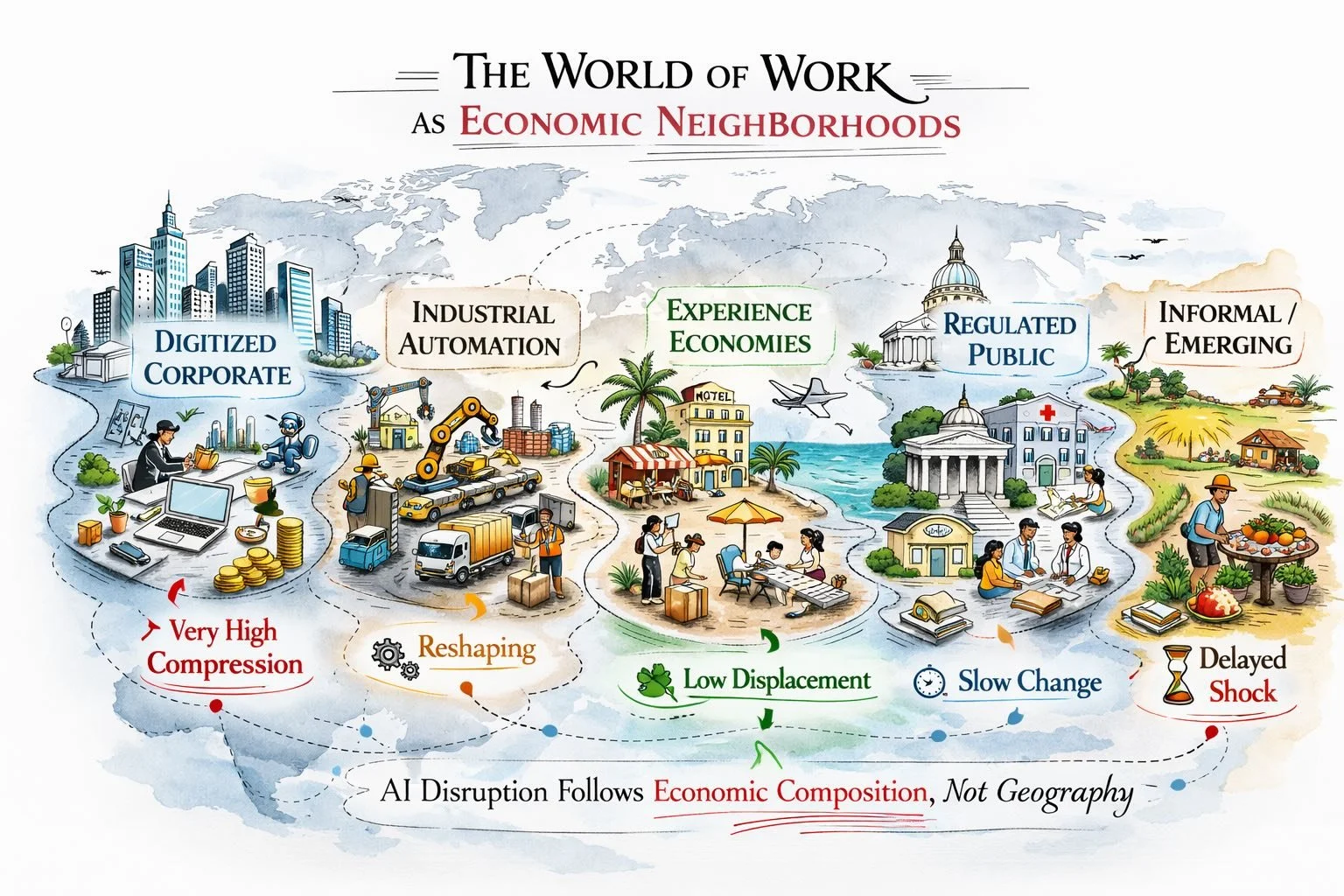

National Exposure to AI—The AI Heat Map: Artificial intelligence is not shaking the global workforce uniformly. Instead, its impact follows the structural fault lines of national economies. Digitized corporate regions built around technology, finance, and standardized knowledge work experience the strongest disruption, where automation rapidly compresses jobs and reorganizes workflows. Industrial economies feel deep reshaping as tasks automate while physical systems slow full displacement. Meanwhile, experience-driven and informal regions remain comparatively stable, where human interaction, trust, and presence define economic value. Regulation further buffers some societies while accelerating others. The future of work will unfold not as a single global shock, but as asynchronous national transitions shaped by economic composition, labor structure, and institutional speed. This visualization is conceptual, illustrating structural exposure patterns rather than precise forecasts. Warm tones (red to orange) represent high near-term workforce compression, concentrated in highly digitized, corporate-heavy economies where routine cognitive work is most automatable and restructuring happens rapidly. Transitional tones (yellow to light green) reflect reshaping zones, where automation redesigns workflows and compresses layers without immediate mass displacement. Cool tones (green to blue) indicate low near-term displacement or delayed shock, common in experience-based, informal, and human-centered economies where AI primarily augments rather than replaces labor.

National Exposure to AI: Why Some Countries Will Feel the Shock Far More Than Others

Just as AI does not affect sectors evenly, it does not affect countries evenly. National exposure to AI-driven restructuring is shaped less by headline adoption rates and more by economic composition, labor structure, and institutional capacity. Countries dominated by highly digitized, corporate, and process-intensive industries face far greater near-term workforce compression than economies anchored in human-centered services, informal labor, and experience-based value creation.

At a national level, AI exposure correlates strongly with three structural factors. First is the share of employment in digitally mediated knowledge work, such as technology, finance, professional services, and large-scale corporate operations. Second is the degree of task standardization and procedural decision-making embedded in the economy. Third is the speed at which firms can legally, culturally, and politically restructure workforces. Where all three align, AI-driven layoffs arrive quickly and visibly. This is why advanced economies such as the United States, parts of Western Europe, and segments of East Asia are already experiencing measurable AI-era workforce compression. These countries concentrate employment in sectors where AI substitutes routine cognition efficiently and where capital markets reward rapid productivity signaling. In these environments, layoffs increasingly function as strategic signals of modernization rather than responses to distress.

By contrast, countries with large shares of employment in tourism, hospitality, retail, cultural industries, public services, and informal economies face materially lower near-term displacement. In places such as Egypt, Greece, Thailand, Morocco, and many parts of Southern Europe, the economic core is built on presence, service quality, trust, and cultural interaction. AI may optimize bookings, pricing, logistics, and administration, but it does not replace the human experience that constitutes the product itself. As a result, workforce compression is slower, more selective, and often confined to back-office functions. National labor market structure further amplifies these differences. Countries with flexible hiring and firing regimes, shareholder-driven corporate governance, and deep capital markets tend to experience faster restructuring cycles once AI narratives take hold. Where labor protections are stronger, public sector employment is larger, or informal work dominates, AI adoption translates into gradual role transformation rather than abrupt displacement.

AI-driven disruption is structururally concentrated, not geographically random. Nations built on digital corporate labor experience immediate compression, while economies rooted in human interaction and informal work remain comparatively resilient in the near term. Technology adoption matters less than where economic value is actually produced.

Crucially, national exposure is not a proxy for national readiness. A country may adopt AI aggressively while still being vulnerable to social and employment strain if reskilling capacity, education systems, and transition pathways lag behind automation speed. Conversely, countries with lower immediate exposure may face sharper shocks later if digitization accelerates without institutional preparation. The implication is that AI will not produce a synchronized global labor shock. Instead, it will create asynchronous national transitions, where some countries absorb rapid workforce compression today, others experience delayed but steeper adjustments tomorrow, and many navigate a prolonged hybrid phase where automation coexists with deeply human work.

Understanding AI’s impact therefore requires moving beyond universal forecasts of “jobs lost” or “jobs created.” The real question is not whether AI will reshape work, but where, when, and through which national economic structures that reshaping will occur. For sectors, you anchored exposure in a globally standardized system (UN ISIC A–U), which gives rigor and comparability. For countries, the equivalent is not another classification system, but a composition-based exposure model. National AI exposure = how much of a country’s economy sits inside high-, medium-, and low-automation sectors weighted by labor structure and institutional speed. In other words, Sectors tell you where AI can automate, and ountries tell you how concentrated those sectors are in real economies and how fast restructuring can happen.

Global AI Exposure Clusters illustrate how workforce impact varies by economic structure: Digitized Corporate economies built around technology, finance, and professional services face very high workforce compression; Industrial Automation economies centered on manufacturing and logistics experience deep reshaping rather than immediate displacement; Experience Economies driven by tourism and hospitality see low near-term displacement as human interaction remains core to value; Regulated Public economies dominated by government, healthcare, and education undergo slow, buffered change; while Informal and Emerging economies anchored in agriculture and informal services face delayed but potentially volatile shock as digitization accelerates.

National AI Exposure Framework: Sector Composition × Labor Structure × Institutional Velocity

Rather than treating countries as homogeneous units, OHK measures national exposure to AI-driven workforce restructuring by mapping each economy’s employment and GDP across the same United Nations ISIC sector framework, then layering three powerful national amplifiers that determine how fast and how severely automation translates into real job compression.

(i) Sector Concentration Risk reflects how heavily a national economy is weighted toward high-exposure industries such as Information & Communication, Financial Services, Professional Services, and Administrative Support, versus medium-exposure sectors like Manufacturing, Logistics, Energy, and Construction, and low-exposure sectors including Tourism, frontline Healthcare delivery, Education, Cultural industries, and informal services. Countries whose employment and output are concentrated in highly automatable ISIC sectors experience faster and deeper AI-driven workforce compression, while those anchored in human-centered services remain structurally more resilient.

(ii) Workforce Structure Sensitivity captures how much of a labor market consists of routine cognitive work, formal corporate employment, and digitally mediated processes, versus informal, physical, experiential, and relational labor. The more standardized and corporate an economy’s work structure becomes, the more directly automation converts into layoffs. Economies built around presence, service, and human interaction absorb AI primarily as augmentation rather than displacement.

(iii) Institutional Restructuring Speed determines how quickly technological change translates into workforce change through labor law flexibility, capital market pressure, shareholder-driven governance models, public sector size and protections, and political tolerance for displacement. Systems that enable rapid restructuring amplify AI’s labor impact, while regulated or socially buffered systems slow compression and favor gradual role transformation.

National AI exposure is not something that can be inferred from adoption headlines or investment volumes—it must be measured structururally. No existing global index captures how automation risk actually propagates through real economies, because most treat countries as monolithic units rather than as sectoral compositions shaped by labor structure and institutional speed.

Putting It Together: A National AI Exposure Index: OHK’s National AI Exposure Index weights each country’s employment and output across UN ISIC sectors by automation feasibility, then adjusts for labor structure sensitivity and institutional velocity to reflect how quickly technological potential becomes real workforce impact. In practice, this produces structurally distinct national trajectories: (i) United States exhibits very high exposure, driven by heavy concentration in technology, finance, professional services, and corporate administration combined with rapid restructuring culture; (ii) Germany and Northern Europe show moderate-to-high exposure, where strong manufacturing automation is tempered by regulation and labor protections that slow displacement.; (iii) Southern Europe remains lower exposure due to dominance of tourism, hospitality, and public services; (iv) East Asia (Japan, Korea) experiences high reshaping with slower displacement, reflecting automation leadership paired with long-term employment norms; (v) Africa and parts of MENA show low near-term exposure, anchored in informal economies and experience-based sectors; and (vii) The GCC faces medium-to-high exposure risk, where aggressive automation strategies collide with fragile labor transition capacity.

Structural takeaway: Across countries, AI disruption follows economic composition rather than geography. Exposure rises where work is digital, standardized, and institutionally easy to restructure; it remains limited where value creation is human-centered, experiential, or socially buffered. The future of work will therefore unfold through asynchronous national transitions, not a single global labor shock.

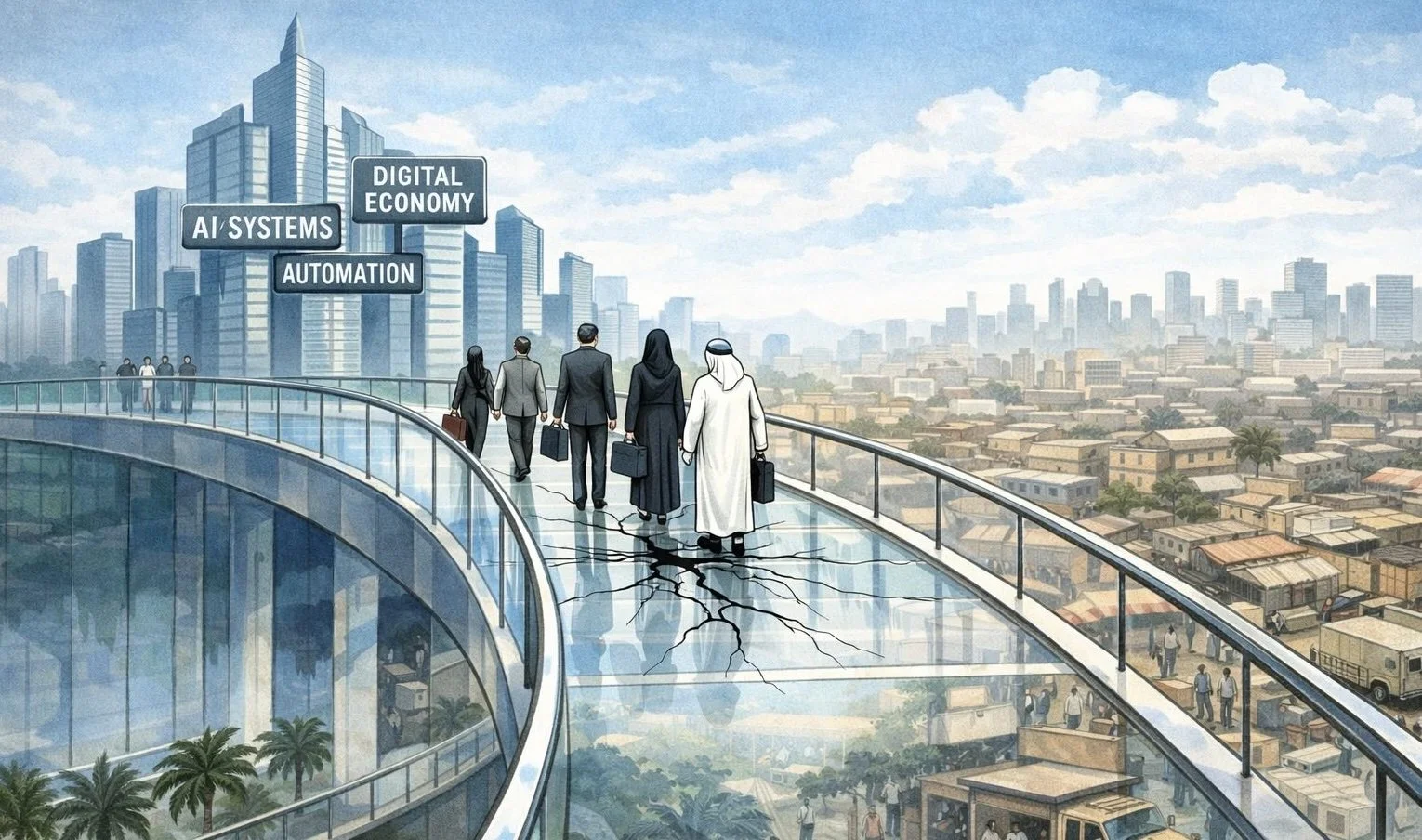

The Gulf is building tomorrow’s AI economy at speed from AI chips to hyperscale data centers, automation platforms, and digital governments while today’s employment engine remains rooted in human-heavy sectors, rising unemployment pressure and a widening skills gap.

AI Ambition Meets The Gulf’s Structural Paradox

Across the Gulf, artificial intelligence has become a central pillar of national modernization strategies. Governments and sovereign investors are racing to secure advanced chips, build hyperscale data centers, launch AI-native startups, and automate everything from public services to logistics and finance. The ambition is clear: to leapfrog into the front ranks of the global digital economy and reduce long-term dependence on hydrocarbons through productivity-driven growth. In other words, the Gulf is building AI infrastructure for an economy that—in structural terms—only partially exists. Also, this technological acceleration sits in growing tension with two structural realities: the sectoral makeup of Gulf economies and the political centrality of employment stability.

Despite diversification efforts, GDP across most GCC states remains heavily anchored in oil and gas, energy-intensive industries, construction, real estate development, public administration, tourism, and large service ecosystems. These sectors generate enormous economic value, but they are not the environments where AI produces rapid, scalable workforce substitution. Much of their output depends on physical infrastructure, regulatory oversight, safety, and human presence. In these domains, automation tends to optimize processes rather than eliminate labor. The sectors that globally experience the fastest AI-driven displacement—technology services, financial processing, professional services, corporate administration, and data-intensive platforms—still represent a relatively modest share of Gulf employment and output compared with advanced Western economies. Therefore, the sectors that dominate Gulf GDP largely fall into the reshaping or augmentation zones of automation rather than full displacement. In effect, the Gulf is investing in frontier AI capabilities—compute power, automation platforms, digital governance— while the core economic base absorbs AI primarily as efficiency enhancement rather than transformational substitution. Productivity may rise, but the expected scale of workforce restructuring and digital sector expansion may fall short of the narratives driving investment.

This would already create a strategic imbalance. But the labor dimension intensifies it further. Across several GCC countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, unemployment — especially among nationals and younger cohorts — remains a central economic and political concern. Large parts of the private-sector workforce are concentrated in precisely the roles most exposed to automation: administrative services, retail operations, logistics coordination, routine clerical work, and basic corporate support functions. Here lies the paradox: AI is being deployed most aggressively in the segments of the economy that currently provide the bulk of employment opportunities—not in the sectors that generate the bulk of national income. Where Western economies often see AI compress white-collar routine work within already digitized corporate sectors, Gulf economies risk compressing lower- and mid-skill employment pools that lack large adjacent high-tech job ecosystems to absorb displaced workers. The result is a potential productivity surge coupled with rising employment pressure.

Efficiency improves. Payrolls shrink. But alternative high-skill job creation does not scale fast enough to compensate — at least not in the short to medium term. This is why massive reskilling initiatives, digital academies, and AI education programs have become central to Gulf policy responses. Yet skills transitions historically take years, while automation arrives in quarters. The real risk is not AI adoption itself; the risk is sequencing failure. When technological acceleration outruns sectoral diversification and human capital transformation, societies experience what economists call productivity growth with declining employment elasticity—more output per worker, but fewer workers required. In this scenario, AI modernization runs directly counter to near-term employment objectives. For the Gulf, the strategic challenge is therefore deeper than managing technological disruption. It is about aligning three transformations simultaneously: economic structure, workforce capability, and automation speed.

Without that alignment, the region risks building one of the world’s most advanced AI infrastructures while intensifying labor market stress—particularly among the very populations national development strategies aim to empower. In this sense, the Gulf is not merely navigating technological change. It is attempting to compress decades of economic restructuring into a few years of digital acceleration— a feat that promises productivity gains, but carries equally significant social and political risks if not carefully paced. The ultimate question is not whether AI will modernize Gulf economies. It almost certainly will. The real question is whether modernization can be achieved without undermining employment stability before new sectors mature enough to replace what automation displaces.

OHK observes that GCC AI ambition is accelerating faster than economic structure can absorb it, creating productivity gains that risk intensifying employment pressure rather than diversification.

This article is part of OHK’s ongoing series on artificial intelligence broadly and the future of work specifically, examining how AI is reshaping organizations, economies, and operating models across industries.

At OHK, our work on the future of work and AI-driven transformation is grounded in real-world organizational redesign, not abstract technology forecasts. We support governments, development institutions, and private-sector leaders in translating artificial intelligence into sustainable operating models that improve productivity while preserving execution resilience, workforce stability, and social legitimacy. From workforce transformation strategies and automation roadmaps to productivity measurement frameworks and policy-ready labor transition planning, we help organizations distinguish genuine AI-driven modernization from narrative-led restructuring that risks long-term correction. Our hybrid expertise across management consulting, economic planning, and international development enables us to design transformation programs that integrate technology deployment with governance capacity, skills development, and institutional reform. If your organization is navigating AI adoption, workforce restructuring, or future-of-work strategy, contact us; OHK can support you in building automation responsibly, measuring impact rigorously, and redesigning work for long-term value creation rather than short-term cost compression.